No care, no medicines: Koiripur PHC reroutes patients to private facilities

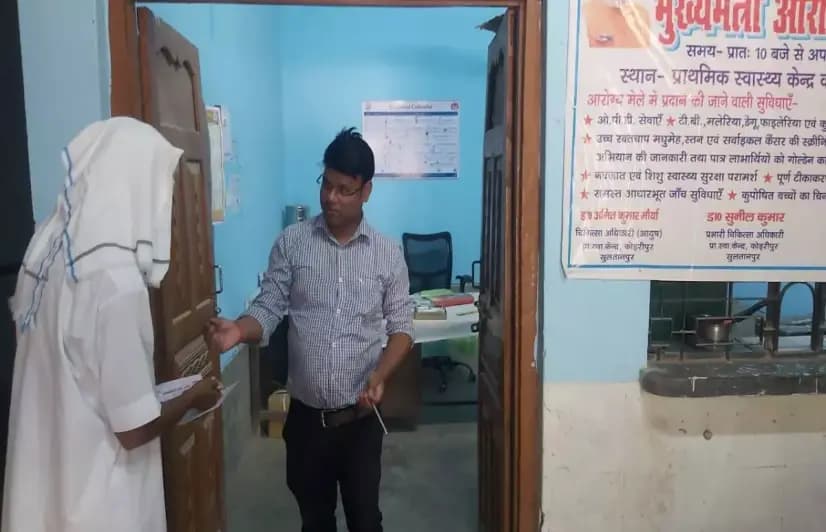

With ceilings that may collapse at any time, admitting patients is a strict no; even pills that are given free of cost at PHCs have to be bought from outside pharmacies Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh: “He won the election and disappeared. We never saw him in our village, leave alone doing something for our betterment.” A resident of Koiripur nagar panchayat in Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh, Rauchi Devi (42) did not mince words when narrating the tale of neglect that haunted a local primary health centre (PHC). Her anger was directed against former nagar panchayat chairman Sudhir Sahu, whose tenure ended recently. Rauchi’s daughter-in-law Zriya Devi (19) recently faced a pregnancy-related complication, and lack of facilities at the PHC exacerbated the ordeal. She had to be rushed to the community health centre (CHC) in Chanda, located eight km away. Though Zriya delivered a baby boy there, further issues made them visit a private hospital. “The doctors in the CHC said the newborn had water in the belly. The CHC was not equipped to treat the condition, so we had no choice but to rely on a private hospital in Chanda,” said Rauchi, whose husband and son work as labourers.Entrance to the Primary Health Centre which serves the Koiripur Nagar Panchayat (Photo - Bilal Khan, 101Reporters) A poll plankAccording to the 2011 Census, Koiripur nagar panchayat has a population of 8,927. Sahu, who once again stood for the chairman’s post in the election held on May 10 and 11, said the electoral rolls had 7,800 voters this time. His contender and newly elected chairman Kasim Raeen told 101Reporters that the majority of the population in Koiripur town lived below the poverty line. “They are the ones who have been suffering badly due to the poor state of affairs at the PHC for over a decade now,” he said.No wonder why the issue played out during the nagar panchayat polls this time. “We were all fed up with the PHC issue. Since we realised that Sahu will not do anything, we ditched him. What is the point in giving vote to a person who does not care for the people,” Rauchi asked. Ideally, a PHC should have one MBBS doctor, two to three female staff to treat women, especially those pregnant, hospital beds, facilities for basic check-up and an out-patient department. As per the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) guidelines, a PHC caters to a population of 20,000 in hilly, tribal or difficult areas and 30,000 in plain areas. One MBBS medical officer and six indoor/observation beds are required. It acts as a referral unit to the CHC for six sub-centres also. In Koiripur, however, the PHC building is so shabby that doctors are scared of working there. Portions of the ceiling may come off any time. “We have medicines for basic issues, say cold, cough and wounds. Equipment for medical check-ups are not available,” Dr Sunil Kumar, the medical officer at the facility since September 2022, told 101Reporters.Crumbling ceilings, broken windows, lack of drinking water, dysfunctional toilets and missing medical equipment are some of the issues plaguing Koiripur PHC (Photos - Bilal Khan, 101Reporters)The PHC has a large room with a few beds to admit patients, but there is no facility for treatment. “Even if things were in place, no patient would be admitted here because of the ramshackle building. Parts of the ceiling fall off quite often,” added Dr Kumar, a Bahraich native.He claimed lack of amenities affected the doctors equally and that he had written to the competent authorities about the issues. “There is no drinking water facility. We buy it on our own. The toilet is in such a bad condition that we cannot use it.” Along with Dr Kumar, a homeopathic doctor also works there. “Healthcare is a big issue here and people have been demanding that the PHC be equipped. But I do not think that was the reason for my defeat,” said Sahu, when asked whether he lost the election due to the poor condition of the PHC.Elaborating further, he said the PHC building was a private property with a monthly rent of Rs 1. Consequently, even the government could not do anything to improve its condition. It took me almost a year to make it a non-rental property and hand it over to the government.”Sahu informed that the health department was in the process of initiating repair works. “I have been in contact with the authorities concerned earlier. Though I am not the chairman now, I am from the Bharatiya Janata Party, which is in power in the state. I will continue to make efforts to make the PHC facilities better," he said.District Chief Medical Officer Dr DK Tripathi was aware of the condition of Koiripur PHC, but did not comment on the timeframe for repairs or the expenses involved. “The building needs reconstruction. We have asked the junior engineer concerned to make an estimate. I cannot say how long it will take to resolve the issue,” Tripathi said. Meanwhile, Sahu estimated that around Rs 1 crore would be required to repair and equip the PHC with necessary medical facilities. Few and far At present, people of Koiripur have no choice but to visit Chanda CHC for medical care. Many try to avoid treatment as expenses are high. Mithailal has been facing respiratory issues for the last three years, but has visited the CHC only twice. Neither did he think about getting a better treatment elsewhere as he could not afford the medical expenses. “The doctor at the CHC suggested medicines for 10 days. It should be given free of cost to the patients, but there was no stock. When I went to a private pharmacy, I found the medicine would cost Rs 3,000 for 10 days. It was not at all affordable. So, I ended up consulting a local doctor (quack), who suggested a medicine costing Rs 500 to 700 a month,” he said. Mithailal does not breathe normally and cannot stand for 10 to 15 minutes as his legs shake. “I have not been working for the last three years. My sons are in their early twenties; they do earn a little through construction labour. Both could study only up to class 8,” he lamented. (Above) Saroj Kumari has been unable to get her son Tirbahavan Kumar the required medicines for his respiratory condition because their local Community Health Centre doesn't stock them; (below) Mithailal resorted to medicines given to him by a local quack after finding that he couldn't afford them at the private pharmacy (Photos - Bilal Khan, 101Reporters)Saroj Kumari did not follow the treatment suggested by the doctor at the CHC when she learnt that the medicine would cost Rs 700 a week. “My son had mucus build-up in throat. The PHC doctor referred us to the CHC, where medicines were not available at the pharmacy. Since I did not have Rs 700 to buy medicine from outside, we avoided treatment.”“We are seven members in the family and there is only one breadwinner,” added Saroj, whose son Tirbahavan Kumar (21) seemed weak and malnourished.If private pharmacies are not affordable, how can private hospitals be? Rauchi claimed her grandson was admitted in the private hospital in Chanda for three days, and the bill came to Rs 16,000. “For us, having this much money at once is a luxury in itself. What my husband and son earn is barely sufficient to put food on the table for all seven in our family. We had no option but to borrow money. We do not know when we will repay it,” exclaimed Rauchi. Asked why they did not visit the district hospital in Sultanpur, she said it was 40 km away and would involve similar expenses. “Admitting the baby in the district hospital means we have to arrange accommodation for three to four days. We also have to buy food thrice a day. We have children at home too.” Pinning hopes on the new chairman Raeen, Rauchi said, “We have high expectations from him. He was once in that post and he did a lot for us.” Meanwhile, Raeen said he had raised the PHC issue during the poll campaign. “Now that people have elected me, my foremost priority will be to get the PHC fully functional. I will talk to the authorities concerned and request them to expedite the process.” Edited by Rekha PulinnoliCover photo - Dr Sunil Kumar, the medical officer at the Koiripur PHC, hands over medicines to a patient (Photo - Bilal Khan, 101Reporters)

Through their organic farming initiative, Mirzapur brothers help over 1500 farmers

40-year-old Radha Devi (left) grows peas, chillies, tomatoes and potatoes on her half-acre organic farm. Chanda Devi (right) looks after her organic farm and also works at the Nav Chetna Agro Centre (NCAC). (Photo Credits- Bilal Khan)Through their farmer producer organisation, the duo has helped farmers — including a notable proportion of women — earn significant profits on their crops using vermicompostingMirzapur: “After my husband’s death five years ago, I had to struggle to raise my two children with the meagre monthly income (Rs 2,000) I earned as a cook at a government-run primary school. It was the training and support I received from Nav Chetna Agro Centre (NCAC) three years ago that turned my life around,” said 40-year-old Radha Devi, who grows peas, chillies, tomatoes and potatoes on her half-acre organic farm.“I grow three crops in a year. On average, I earn around Rs. 1.5 lakh annually from the farm. It’s made life easier for me and my children. At the agro centre, I do vermicompost cleaning and packaging, and also take care of the beds,” said Radha, who also works part-time for the centre for Rs 6,000 per month.Radha is one of the 640 women from 15 villages in Uttar Pradesh’s Mirzapur district who turned to organic farming after being trained by the NCAC, a farmer producer organisation (FPO)— a government-registered group engaged in vermicomposting that provides end-to-end support and assistance to member farmers, including technical services, marketing and other such aspects of agriculture. Besides training farmers in organic farming and helping them procure necessary equipment, the NCAC also purchases their produce at prices up to Rs 5 per kg higher than what they would get locally, and then markets it across Uttar Pradesh. Also, in appreciation for its services, the state government provides the NCAC financial support and subsidies on the machinery it purchases to help the farmers. It also received an award from Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath for being the best FPO of the state. A product of nobilityThis FPO was brought to Mirzapur by two well-meaning brothers who hail from the district’s Sikhar village. Mukesh Pandey used to earn a lakh a month as a training consultant for the International Labour Organisation in rural Gujarat and Jharkhand. But he left the well-paying job because he “wanted to do something for the villagers in my state”. His brother Chandra Mouli Pandey, on the other hand, owned a business in Varanasi, but joined Mukesh when he realised he needed help managing the vermicompost business.“I used to earn Rs 2,000 a day from my business,” said Chandra Mouli. “But when I realised the potential in vermicomposting, I decided to join my brother.”When the brothers started the operations in Mirzapur in 2017 with only two vermicomposting beds, they found marketing a major challenge. While they intended to encourage farmers to turn to organic farming, Mukesh said spreading awareness about its benefits was a tough task. “Sales started gaining momentum after we conducted awareness drives in the form of street plays,” Chandra Mouli added. “Another obstacle was the social stigma associated with a business that used cow dung as a raw material. The villagers used to look down upon us.”Chandra Mouli (left) taking care of the vermicompost beds. Rishikesh Mishra (right), 24 year-old farmer at his organic farm. (Photo Credits- Bilal Khan)Finally, when the farmers in nearby villages began to turn to organic farming, they set up the FPO to support them. The NCAC now has around 1,000 vermicompost beds in the village of Sikhar and sells its organic fertiliser in 12 states, including Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Chandigarh as well as Jammu. “Our business crossed the Rs 1.5-crore mark in annual turnover in 2020-21 fiscal, but our real feat is having managed to help 1,560 farmers take up organic farming. Of these, 60 per cent are women,” claimed Chandra Mouli. “Earlier, these women had no income of their own. The male members of their families earned money through odd jobs in the village or by migrating to cities.”Benefits of organic farmingThe FPO’s director Rajnikant Pandey, also a farmer, told 101Reporters that using chemical fertilisers increased the cost of farming every season while simultaneously reducing the profit farmers made. “Such fertilisers also reduce the fertility of the land and, in turn, farmers’ income. However, the use of organic fertilisers such as vermicompost increases the fertility of the soil and, in the long run, reduces the cost of farming by around 60 per cent. As a result, farmers earn higher profits,” he explained.Rajnikant, who had 14 acres of land, turned to organic farming around four years ago after attending an awareness campaign organised by the NCAC.“In 2018, I earned Rs 6,00,000 from cultivating peas,” he said with pride. “Switching to organic farming increased the yield as well as the price I received for the produce.”Migration reversalThe success the NCAC member farmers saw in organic farming set off a reverse migration trend in the villages. Chandra Mouli told 101Reporters that around 40 men in his village had returned from cities, where they had migrated in search of work, after they saw the women in their families earning a decent income through organic farming.Chanda Devi, a resident of Biththalpur village, is among the many women who have benefited from the NCAC. In fact, her husband Uma Shankar recently left his work at a construction site in Delhi and returned home.“My husband earned around Rs 12,000 a month, but it was not enough to manage the expenses of our three children,” she said. “Last year, when he realised that I could manage to make around Rs 2,00,000 a year by growing crops such as peas, chillies and tomatoes in our three-bigha farmland, he decided to join us.”Today, Chanda also works at the FPO and draws a monthly salary of Rs 6,000. Similarly, Rishikesh Mishra, a 24-year-old farmer in Lalpur village of Shikhar block, used to work with a manufacturing company in Gujarat for Rs 15,000 per month. “It was a struggle despite working hard, living away from my family. It was then that I heard about several farmers turning to organic farming and making good profits. I also gave it a try and was successful,” said Mishra, adding that he now earned around Rs 3,00,000 annually from growing chillies and peas. “I’m also planting bananas 100 percent organically. They will be ready for harvest in the next 13 to 14 months.”Mukesh Pandey (left) and Chandra Mouli (right), the Mirzapur brothers who started NCAC. Shashikant (centre), an investor in the business. (Photo sourced by Bilal Khan)There’s more: the FPO was of immense help all through the Covid-19 outbreak, especially when scores of migrant workers were forced to return to their villages during the lockdown. Mahendra Tripathi is one such individual who is grateful to the organisation. He worked with a Kanpur-based company for Rs 10,000 a month, but lost his job when the entire country went into lockdown. He returned to his native place, Bhualpur, and joined the FPO to market their vermicompost fertilisers. “I now earn around Rs 25,000 per month,” he told 101Reporters.

Community participation helps students in this UP village continue studies during pandemic

Mohalla classes, facilitated by the teachers of a primary school in Durawal Khurd village of Uttar Pradesh, has helped students continue their engagement with studies, despite the lockdowns and lack of smartphones. Varanasi: When the lockdown was first imposed in 2020, studies came to an abrupt halt for 12-year-old Sakshi Shukla, a sixth-grader in a government English-medium primary school in Durawal Khurd village of Uttar Pradesh's Sonbhadra district. There was only one smartphone in her family, which belonged to her father. And he carried it wherever he went, meaning the phone was never available for her online classes.Most of her classmates did not have even the one phone. The village, whose residents are primarily engaged in farming or work as labourers, also has very low internet connectivity. So for 11-year-old Suraj Chauhan, the lockdown and school closures left him feeling completely disconnected from his studies. No one in his family had a smartphone and there was no one around to teach him. Initially, Suraj tried to study by himself with the textbooks he had. “But I began losing interest in my studies. I missed school where I used to study and play with my friends,” said Suraj, who is now in 6th grade. Suraj’s father, Suresh (34), is a daily wage labourer and lives in a kutcha house with his family of four children, his wife and his parents. He earns around Rs 4,000 a month. “It’s a village. We don’t get work every day. It is tough to run a house with so little money, but I don’t have a choice. How can I afford a smartphone and internet recharges monthly?” questioned Suresh. Suraj Chauhan's home where he lives with his parents, grandparents and three siblings (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)The primary school of Durawal Khurd has about 150 students. “We had only 30 parents on our parents and teachers WhatsApp group. This shows the availability of smartphones and internet connectivity in the village,” said Raj Kumar Singh, the headmaster of the school.He explained that it was tough for them to teach the students online when the students had no way of attending online classes. “We could have left the students disconnected from their studies, stating the reason that their families had no smartphones or internet connectivity. But, we as teachers have the responsibility to provide education to our students and help make life better for them. That is why we came up with an idea called mohalla classes,” said the headmaster. These are classes conducted with the help of a few educated volunteers in the village who have smartphones, and who can be guided by the teachers.Your friendly neighbourhood schoolThese classes have been hugely successful in keeping the students engaged in studies during the pandemic and the government has replicated this initiative throughout the state. With apps like Diksha and Read Along, students are now learning with ease. “The apps were launched by the government but the teachers and volunteers taught us how to use them for studies, which was very helpful. Now we learn various stories, poems and other things from the apps,” said a happy Sakshi. For the mohalla classes, the teachers of the school found a few educated people from the village who had smartphones and internet connectivity. The primary school teachers trained 10 such volunteers, including women, from the village. Kamlesh Kumar, who is a teacher in the school said that the volunteers, also known as Prerna Sathi or 'inspiration partner', have all at least passed their intermediate exams. The teachers trained them to teach the students and also guided them to follow Covid safety protocols. The teachers also created nine locations or centres where the students and the mohalla class teachers gathered for studies. A Mohalla class in session (Picture credit - Bilal Khan) “We would share online study materials to these trained volunteers and they, in turn, taught the students for at least one hour every day, in the mohalla classes. We made sure that social distancing was followed, masks were worn and sanitiser use was practised during the mohalla classes. Even the school teachers would visit the village’s mohalla class centres to teach the students,” explained Singh. Overcoming reluctanceInitially, when the volunteers tried to convince students to join a mohalla class, there was reluctance. “The idea was not appreciated as something special or unique. Moreover, parents were scared that the children could get infected by the coronavirus. But when they soon saw students gathering one by one, all the students began taking it seriously and enjoyed the mohalla class sessions,” said Seekha Shukla, a 32-year-old Bachelor of Arts graduate and a mother of two who is one of the mohalla class volunteers. Seekha Shukla, one of the volunteers, at her home with her daughter (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)Initially, even the volunteers were scared of infections. “But if we would not come forward, who would teach the children from families that did not have smartphones? Moreover, we were following all Covid safety protocols,” said Shukla. “Disconnection from education, even if it is for three to four months, can make children forget what they have learnt. Imagine how much they would have lagged behind if they were not engaged in education through any means,” said Rajesh Kumar (30), a mohalla class volunteer who moved back to his village from Maharashtra before the first lockdown was imposed. The teachers of the primary school stay far away from the school and the village. But they would often visit the mohalla classes to meet the students and guide the volunteers. “It was risky because all our teachers stay more than 10 kilometres away from the village. We would always be worried that the students, who are between five and 12 years of age, would get infected by the coronavirus because of us. But education disconnection is also risky for the children’s future. We chose to risk our health, but it was a mindful and conscious risk,” stated Anil Kumar Singh, a teacher. A success storyThe unique initiative of mohalla classes ensured that the students continued their education during the several months that the school was shut. The students and parents alike are elated at the success of the initiative and extremely thankful to the teachers and volunteers for it. Singh believes that the initiative has been a saviour for students during the lockdown. “Although it was not as effective as school classrooms because we would have less time in mohalla classes, we are happy that the students are as versed as they were before the lockdown was imposed,” he said. The teachers at the Durawal Khurd primary school (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)Singh said that if the mohalla classes were not conducted, parents may have engaged their girls in other home chores. “It is the village people’s mentality that boys are given more importance in education than girls. This could have ruined girls’ education during the lockdown but mohalla classes came to their rescue. The mohalla classes saved many girls from discontinuing their education,” he stressed. “Our children were not away from education and hence they did not forget what they have learnt. The teachers could have shrugged their shoulders as we had no smartphones and internet, but they fulfilled their responsibility. I am very grateful for this to the teachers,” said Ratneshwari Devi (33), a parent of one of the students of the primary school. When the officials noticed the benefits of the mohalla class initiative, it was launched officially across the state. “We are thankful to the officials for noticing our work and launching our model across the state. This shows how successful and beneficial our mohalla classes were for the students, especially for those who had no smartphones and internet connectivity,” exclaimed Singh with pride. Safeena Husain, Founder of Educate Girls, highlights, “Mohalla classes, also called community-based learning, not only helped children stay in touch with education but also helped maintain their social connections during the lockdown. It has definitely helped in curbing incidences of domestic abuse and violence against children to a certain extent.” She added, “These marginalised children have also learnt to safeguard themselves with proper sanitisation practices, which has been another learning for them.”

Kanpur's trans* folk get vaccinated without having to endure humiliation

A special vaccination camp welcomed members of the LGBTQ community who had earlier either stayed off vaccination centres fearing harassment and humiliation or were denied the vaccine over inaccurate gender information on identity documents. Kanpur: Misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine is discouraging certain sections of the population from taking the jab, but for the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer) community, the battles are different. Humiliation and harassment by the public while waiting for their turn in queues have become the norm and are often followed by denial of the vaccine by personnel manning the vaccination centres over incorrect gender information in their identity documents. Tarana Kapoor (19), a member of the transgender community in Kanpur city, went to a COVID-19 vaccination centre in late September to receive the shot. Although she managed to get the vaccine, she said she had to suffer much humiliation. “I felt embarrassed because people were staring at me as if I was an alien. Even though initially I thought of leaving the place without receiving the vaccine, I decided that I should not lose heart because I am different. I stayed till I received the vaccine,” Kapoor told 101Reporters. “The social stigma against the LGBTQ community is one of the main reasons behind its members shying away from visiting vaccination centres. We do not want to face the discrimination and humiliating stares from the public. We are humans too,” added Kapoor. Such discrimination is the reason why the percentage of members of the LGBTQ community vaccinated against COVID-19 is low. According to the government, 120 crore Indians have received at least one dose by mid-November, but this includes only 2.7 lakh members from the community – a little more than half of the registered third gender population in India. Another major hurdle members of the community are facing are discrepancies in their identity documents regarding their gender. And citing this, personnel at vaccination centres often refuse to administer the vaccine to them. Mariya Yadav (26), a transgender woman in Kanpur, told 101Reporters that after a long wait in the queue, ignoring disturbing stares from others, she was denied the vaccine at a vaccination centre in early September. “The gender mentioned in my Aadhaar card is male. The personnel at the centre told me that my appearance and the way I talk did not match the gender mentioned in the document, and hence, they could not administer the vaccine. It was humiliating to explain to them that I was born male but underwent sex reassignment surgery (SRS) six months ago. I was embarrassed and left the place deciding not to take the vaccine ever,” said Yadav. However, Yadav took the vaccine at a two-day camp organised exclusively for the LGBTQ community at Bal Bhavan Phool Bagh in the city by Kanpur Queer Welfare Foundation from October 12. “There was nobody to judge them or question the mismatch of gender information in their identity documents,” said Anuj Pandey who, along with his partner Shaan Mohammed, co-founded the NGO. “I was excited when I came to know that the NGO was organising a vaccination camp exclusively for us. At the camp, I was vaccinated without being humiliated, alienated or judged for my sexual orientation. It was a very comfortable experience for us,” said Mariya, adding that more such camps should be organised for the community. Besides, because of lack of awareness, many community members also fall for the myths, rumours and misinformation being spread about “dangerous after-effects” of the vaccine, and avoid taking the vaccine. “They believe that the government is against the community and is trying to wipe them out with the vaccine. They think that the vaccine causes severe health complications in persons who are in transition or have undergone SRS, which would kill them within in a year,” said Pandey, adding, “Some people do suffer a bout of fever, headache and body pain after the vaccination, but it is normal. Baseless rumours are spreading a scare among people about the vaccination,” Pandey said. The NGO, which has been working for the welfare of the LGBTQ community in Kanpur for more than two years, conducted awareness campaigns for about three months before organising the two-day vaccination camp. It has also been supplying grocery and hygiene kits to the community since the outbreak of the pandemic. According to the NGO’s records, Kanpur has more than 1,000 transgender persons, and it was expecting at least 500 of them to attend the camp. “Only around 250 persons received the vaccination at our camp. However, it has encouraged many other members of the community to approach the common vaccination centres to receive the vaccine. This is a huge feat for us,” said Pandey who thanked the district magistrate and other administration officials for giving them approval to organise a vaccine camp exclusively for the LGBTQ community. “We organised meetings as well as formed WhatsApp groups for the community to educate its members about the importance of the vaccination and encourage them to come forward. We have managed to convince at least 50 percent of the community that the vaccine will not harm them. We have also urged the district magistrate to issue an order not to deny vaccination to members of the LGBTQ community over discrepancies in their identity documents and accord them priority at the vaccination centres. He has agreed,” said Pandey. District Immunisation Officer (DIO), Amit Kanaujia, agreed that the camp was the need of the hour. “Apart from the social stigma associated with the community, its members are also financially most affected because of the pandemic and cannot afford to pay for the vaccine. We will organise more such camps for the community with the help of Kanpur Queer Welfare Foundation,” he said.

This UP village's decrepit health centre is putting infants at risk

Lack of basic medical facilities in Jarai Kalan has resulted in many mothers losing their newborn babies while government apathy and bureaucratic inefficiency delay solutions.Jarai Kalan, Sultanpur: Shankar Ram and Manisha Singh, a married couple from Jarai Kalan village, were delighted at the birth of their baby boy on September 5 this year. Since there weren't any adequate medical facilities in their village or those nearby, the couple had stayed in their grandmother's place in Maya Bazar, Faizabad, until the delivery. The baby was born at a private hospital there, and after being discharged, the family returned to the village. However, their happiness was short-lived when the baby suddenly developed a fever within a few hours of their return. The new parents ran from one hospital to another seeking treatment, but their frantic efforts ended in tragedy as their barely two-day-old infant died in the district hospital in Faizabad, about 50 kilometres away from their village. "The roads are so bad that it takes almost two and a half hours to reach there from the village," said Ram.A harrowing ordeal"We first called the doctor at the hospital where our baby was born. He suggested that we consult a child specialist. Where could we find one when we don't even have a proper healthcare facility in the village?" questioned Ram.Recalling the ordeal, he said, "I hired a Bolero car and visited the Haliyapur Primary Health Centre (PHC) first. They don't have any [good] facilities. We then went to the private hospital where my baby was born. But it was late in the night, so they turned us away due to the unavailability of doctors. We then rushed to Faizabad district hospital. There, after an hour and a half, my child was declared dead. The reason for his death is not yet clear, but we have lost our first and only child," Ram said. The Haliyapur PHC is about 3.5 kilometres from the village. Ram believes that his child could have been saved had there been a functional health facility in the village. "A healthcare sub-centre is available in the village, but it has been in severe disrepair for years. Doctors do not work here because of the dilapidated building. I could have saved my child if the healthcare centre had been equipped with the necessary facilities. It was just a high temperature which could have been treated by immediate medical attention," said Ram, grieving the loss of his child. Shankar Ram's wife, Manisha Singh, who lost her two-day old infant son this September; (right) The abandoned and crumbling sub-centre in Jaria Kalan (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)A sub-health centre or sub-centre provides an interface with the community at the grass-root level, providing all the primary healthcare services for a maximum of 5,000 people. Staffed with at least one auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) or health worker, the sub-centres are meant to have maternal and child healthcare services and trained nurses for delivery and childcare.More tales of miseryRam and his wife are not the only couple to have lost their newborn child due to the unavailability of medical facilities in the village. Raja Singh, who looks after all the responsibilities of the village pradhan, said that the sub-centre has been non-functional for more than 15 years now. "The village has lost about 150 newborn children, including babies who died in-utero due to the healthcare centre being defunct," Singh informed 101Reporters.Phul Kali (55), from the neighbouring village Pure Basu (which falls under the Jarai Kalan gram panchayat), lost her daughter's unborn child two years ago because of the absence of a medical centre in the village. Before they could reach any hospital, she went into labour, and the baby's head slipped out, resulting in a stillbirth. "The nearest hospital we have is Haliyapur PHC. But to get there, we need a vehicle because there is no public transport facility in the village. We survive on irregular wages doing manual labour. How can we afford any vehicle? Ambulances have no fixed time to arrive. If they are far away, they take a lot of time. We somehow managed a vehicle for my daughter, but when we were on the way to the PHC, we lost the baby," Phul told 101Reporters. She claimed they had to spend lakhs on treatment after the baby died in her daughter's womb. Phul decried, "If the healthcare centre in the village were working, I would be playing with my grandchild now. This medical centre needs to be opened as soon as possible, or else we poor people will continue losing children."Another couple from the village, Anand and Pooja Tiwari, also lost their newborn baby girl on June 3 this year. "We were happy to see that our baby was healthy. We were able to pay the bill of Rs 12,000; We opted for a private hospital because we wanted our baby healthy and alive," said Tiwari, who works as a driver and earns around Rs 6000 a month.However, their baby developed respiratory problems. "In just half an hour, we lost our child. We did not have time to see doctors as the hospitals are far away," said Tiwari. "We would have got immediate medical attention if the village had any healthcare facility. The absence of healthcare centres has been causing us huge problems for years," he added, saying that he tried to seek the local ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) worker's help for his child, but to no avail. The state of the Jaria Kalan sub-centre; (right) Anand and Pooja Tiwari lost their new-born daughter in June this year (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)"We have been requesting pradhans for years, but they say that there is no budget to repair the sub-centre. Nobody sees or understands our plight," said Jogi Ram, a resident. Picture of official apathyThe sub-centre in the village is so derelict that its doors and windows are broken and the walls could fall at any time. "Because of the building condition, the doctors posted here don't visit the hospital at all," said Raja Singh. He further said that five villages come under the Jarai Kalan gram panchayat and are under five kilometres from the health centre. "About 10,000 to 12,000 villagers would benefit from the sub-centre. It should be repaired and functional as soon as possible," added Raja Singh. Rekha Maurya, the ANM posted at the sub-centre, confirmed that it cannot function without proper renovation. "The building is so run-down that we can't risk our lives sitting there. Despite the pathetic condition of the building, the government has not provided any facility here," said Rekha. She added, "I have been requesting officials for months, but they have only given us promises that it will be restored and open for villagers soon." With just one sub-centre to cater to five villages' medical needs and emergencies, it has become imperative for concerned authorities to prioritise the complete renovation and installation of a fully functional health centre. However, the government continues to pass the buck at the cost of more infant fatalities.The scene inside the sub-centre in Jaria Kalan, Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Close to 12,000 people are dependent on this health centre (Picture credit - Bilal Khan)The Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of Sultanpur said that he has already sent estimates for restoration work of the sub-centre on May 25, 2021, to the government. "We have 12-15 sub-centres across the district that are in bad condition amongst 115 centres. I have sent the estimates to the state government for repair works for all dilapidated centres, but I am yet to hear any response on it," the CMO told 101Reporters.

Rural Sultanpur's 'covid warrior' pradhans battle vaccine hesitancy

Sultanpur's village Pradhans are walking the talk to get more people to accept vaccines.Sultanpur: On a warm summer day of May 2021, Mandani Singh (40), an ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) from Banbahasirkhinpur in Akhand Nagar block in Uttar Pradesh’s Sultanpur district, was on duty as part of the frontline team inviting villagers to get vaccinated. As Singh, who has been an ASHA for the last 15 years, was speaking to people about the vaccine's benefits, one of the villagers started verbally abusing her. “We were, as usual, trying to explain to the villagers the importance of the vaccine in the fight against the coronavirus. But the man used vulgar language and threatened us with violence if we tried to convince him further,” said Singh. The situation became so intense that the local police had to be called to sort it out. The ASHAs then became wary of pushing the cause of vaccination amongst villagers. “We were scared,” she added. This is not an isolated case. Vaccine hesitancy is being observed amongst several villages of Sultanpur district. Dr AP Tripathi, who is in charge of the CHC (Community Healthcare Center) in Sultanpur’s Dubeypur block, said that “more than half of the villagers are hesitant to get vaccinated because their relatives told them that they would die because of it. They connect even natural deaths to vaccines. However, no deaths have been reported in the district because of the vaccine.” Dr Tripathi felt that this hesitancy is prevalent amongst those who are not educated, as they more easily believe in rumours spread through social media and word-of-mouth. “When a vaccination camp was set up in a village, only 30 people came forward to get jabbed. It was a huge disappointment for us. However, the number of people increased to 100 people during the second camp,” he added. Nanhelal (39), a potter from Dubeypur block’s Narharpur village, wasn’t one of them. He didn’t even let his 55-year-old mother get vaccinated. “No one is ready to get vaccinated in my village. We have heard from many people that the vaccine is not real,” he said. Many villagers also believe that the vaccine will cause ‘incurable diseases’ or kill them. A vaccination camp underway in Kanpa village of Baldirai tehsil in Sultanpur (Picture courtesy: Bilal Khan)Vaccination numbersAccording to Dr AN Rai, the District Immunisation Officer (DIO) of Sultanpur, ‘the district has 5,25,721 people aged above 45. Out of this, 1,64,911 have taken the first dose, and 33,911 have taken the second dose.’ In the 18-44 age group, 19,304 of 1018304 have been vaccinated as of June 13, despite there being no reports of vaccine shortage in the district. This makes up only about 2% of the population in this age group. It was also observed by the Pradhans, officials and doctors that Muslims appeared to be more hesitant about taking the vaccines than other communities.Pradhan Firoz Khan from Dhahafirozpur, Dubeypur block, said that Muslims are more scared because of the political climate. “Many of them think that the coronavirus isn't real. And that all this is just a conspiracy by the government in power to reduce their population. Because of misinformation spread through Whatsapp and word of mouth, they think the vaccines will kill them,” he said. Dr Tripathi also echoed this, saying illiteracy among Muslims makes them more susceptible to rumours and deepens vaccine hesitancy. “That is why we requested a few Muslim clerics to spread awareness during sermons so that the community will come forward to get vaccinated,” he said. Warriors against misinformationConsidering the level of vaccine hesitancy in the region, officials are using various methods to motivate people to get the vaccine. They are seeking help from religious leaders, important local personalities, and anyone they think can influence the residents positively. The District Magistrate of Sultanpur, Raveesh Gupta also acknowledged the efforts of Pradhans in those villages where the highest number of people turned up for vaccinations. “We, as frontline workers, took the vaccine first so that villagers would be motivated. Religious leaders and people who have some dominance or power in the villages are cooperating with us to convince people by taking the vaccines themselves and creating awareness. The Pradhans are also being honoured for the same,” said Dr Dharmendra Tripathi, Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of Sultanpur.So far, 30 Pradhans of different villages have been honoured as ‘Corona Warriors’. Raja Singh, the Pradhan of Jarai Kala Village of Sultanpur’s Baldirai block, has managed to get 500 villagers of 8200 vaccinated so far. Many of them have also taken the second dose. Singh went door to door to convince villagers to get vaccinated. “There was fear in many villagers due to the rumours around the vaccines. But as more and more people from the village came forward to get vaccinated, many more mustered the courage. Now the entire village is ready to get vaccinated. Apart from motivating the villagers, I also provided a transport service so that they could travel to the vaccine centres for free,” said Singh, one of the awardees. Dharmendra Tiwari, the Pradhan of Kanpa village of Baldirai tehsil, was also honoured as a Corona Warrior by the District Magistrate. Initially, Tiwari had struggled to get even a single villager vaccinated. However, he convinced them by getting his mother vaccinated first when the camp was set up in May. After that, many came forward.“Slowly, villagers are now getting vaccinated at the centre nearby. When my mother, who is a senior citizen, got vaccinated, villagers were convinced that the vaccine was good for them and will help them fight against the deadly coronavirus,” said Tiwari. More than 250 out of 5,800 voters in Kanpa village have been vaccinated so far, according to the Pradhan. It is hoped that the Pradhans’ tactics coupled with aggressive awareness drives will create a similar impact in the district’s other villages.

Mumbai's ration shops cheating the poor, hoarding their food

Mumbai, Maharashtra: Kaisar Abdul Rashid, a 42-year-old plumber from Mumbai’s Malad area, used to earn around Rs20,000 a month before COVID-19 struck and forced India to impose a lockdown. The sole breadwinner of his family, he didn’t have a source of income for months and is still struggling to make ends meet.With seven mouths to feed in his house, he’s entitled to 35kg of rations under the National Food Security Act — 5kg of rations (2kg of rice at Rs3 per kg and 3kg of wheat at Rs2 per kg) for each family member. But he received only 10kg of rations this February and hasn’t received over 15kg a month since the lockdown was first imposed in March 2020. “Plus, the condition of wheat [supplied in February] was so bad that I had to refuse,” Rashid says. “The rations should be good enough to eat. We are human beings, not animals,” he rues. “Today, I somehow earn around Rs12,000 a month by doing odd jobs. It’s hard to feed a family of seven in such a situation. We can’t argue with ration shop vendors. If we do, they either refuse to give the ration or use abusive language.”Rashid and his family are not alone in this suffering in Mumbai. Asha Thombare, a 70-year-old from the city’s Chembur locality, alleges that she and her family had been refused rations under the claim that their income was over what would make them eligible for subsidised wheat and rice. This, even though they possess a saffron ration card, which is issued to families with an annual income of Rs15,001 to Rs1 lakh.“My elder brother’s wife earns Rs5,000 a month as a housemaid. My elder brother, who used to do odd jobs, didn’t have a source of pay during the lockdown. It’s tough to manage our household expenses. In reality, there’s no one to earn in my house since the lockdown. The subsidised rations could have eased our turmoil but we now have to buy rations from general shops at the market price.”Rashid and Thombare’s situations bring to light the rampant misappropriation of rations across Mumbai and the predicament the poor ration card-holders of the city are in as a result.Vendor: It happens across stateUnder the National Food Security Act 2013, families with weak financial backgrounds are issued rations cards so they can avail rations (rice and food grains) at subsidised prices from fair price shops. After the central government enforced a pandemic-induced lockdown across India, it announced an additional 5kg of free rations (rice or wheat) for identified beneficiaries. The Act, however, covers free supplies only for families whose annual income is Rs59,000 or less, which leaves out a significant proportion of ration card-holders who earn between this amount and Rs1 lakh. Despite these provisions under the law, vendors at these ration shops often withhold the full quota that is owed to ration card-holders for a host of reasons. The situation was only exacerbated by the lockdown, when more and more people who lost their jobs during the pandemic approached these ration shops to put food on the table. During lockdown, the centre had announced an extra 5kg of free rations for beneficiaries. While vendors admit to the wrongdoing, they justify their actions under the garb of low compensation from the state government. Take the case of Narayan, a shopkeeper from Mumbai’s Govandi area, who did not want to be identified by his surname.He says they have to resort to such means to meet the expenses involved in running the ration shop. “The government gives us Rs1.50 per kg of ration as a commission,” he says. “Suppose we receive about 12,000kg of rations for 400 card-holders. This means we make only Rs18,000 in a month. But there’s rent to pay, plus electricity bills, salaries of employees and charges for the labourers who drop off stock from the government at our shops. These expenses amount to around Rs30,000 a month. It is impossible to bear these expenses if we don’t take away at least 5kg of rations from every ration card-holder.” Rajendra Jaiswal, a vendor from Chembur, backs Narayan’s stand. “This happens across Mumbai. I would say it happens across Maharashtra,” he says. “If the government wants us to stop using such means, it should pay us for all the expenses we incur.”There are figures to back the claim that shopkeepers are indeed involved in the illegal business of not supplying beneficiaries what they are due. According to Prashant Kale, Additional Deputy Controller of Rationing (Mumbai), the government collected Rs33,78,978 from ration shop vendors in the city between April 2020 and January 2021 in fines for stealing rations from consumers. Kale, however, agrees that a commission of just Rs1.5 per kg is too low for them to sustain their business. “But it’s not in our hands,” he adds. “The state government decides the commission. Those who have a problem with this should approach the state and demand more,” he adds.Volunteer group comes to rescue A group of around 15 people in Mumbai has taken it upon itself to tackle this menace and get the eligible folks their complete quota. The group, named Govandi Against Corruption (GAC), has been carrying out awareness campaigns on ration quota since April 2020 and educating card-holders on information they should have at their fingertips.Members of Govandi Against Corruption. Credit: GACAkbar Ali, a ration card-holder from Mumbai’s Shivaji Nagar neighbourhood, earned around Rs10,000 by running coaching classes pre-lockdown. But that came to an end in March last year. Before GAC came about, he was unaware that card-holders could check their ration quota online. Doing this helped him realise that his ration shop vendor had been duping him for years.“I’m entitled to 40kg of wheat and rice but have been receiving not more than 30kg to 35kg,” Ali says. “I argued with the vendor for my full quota after I checked the figure online, but in vain. I can’t do anything but accept whatever I’m getting because the vendor may stop giving me rations or abuse me verbally if I complain."GAC believes that such siphoning of supplies has been going on for years at ration shops but it came to the fore even more clearly during the lockdown, when scores of beneficiaries lost their livelihood and had to turn to these shops to survive. Ateeque Khan, the head of the group, emphasises that this form of extortion is rampant across Mumbai. “I can say that every ration shop siphons the card-holders’ rations and sells them at a higher price to others,” Khan claims. “They sell wheat and rice at Rs10 to Rs18 per kg. This is a huge scam across Mumbai,” he alleges. GAC began as a team of three that tended to complaints of ration card-holders in Maharashtra, especially Mumbai. It now has around 15 members of teachers, corporate professions as well as students preparing for UPSC and other competitive exams. “Initially, we used to receive some 800 calls every day. Many would complain that they were being sent home empty-handed while some would complain about not being given the quota they were entitled to,” Khan says. “Many would also accuse vendors of getting abusive when they demanded their quota. This started when we shared a video online explaining how card-holders could find out their ration quotas.”Awareness drive by the Govandi Against Corruption group. Credit: Bilal A KhanThe group was instrumental in exposing one such shopkeeper in Shivaji Nagar and having his store shuttered. Khan says the rationing officer they approached lodged a police complaint against the vendor for withholding rations and ultimately ordered his shop closed. Their vigilance, however, comes at a price. Khan claims that the group has been receiving threatening calls from goons to dissuade them from creating awareness among the beneficiaries. “This scam is a huge source of income for man,” he claims. “But we will not stop doing what we do because we know how the poor suffer if they don't receive sufficient rations,” he signs off.

UP district's crappy claim of no open defecation

Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh: The state of Uttar Pradesh was declared Open Defecation Free (ODF) under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) in 2019. In other words, the state has built enough toilets for its 200 million people so they don’t have to defecate in the open. However, the ground reality is quite different, at least in the district of Sultanpur that comprises 1,741 villages.Most of the people here continue to relieve themselves behind bushes or in open gutters because their toilets are either broken or half-built. The local pradhans and residents blame it on the lack of funds, 101Reporters found during a visit to Sultanpur recently.Ram Manorath Yadav, who’s the pradhan of Nonara gram panchayat in Sultanpur, says they need at least Rs35,000 to build sturdy toilets and to maintain them. “We receive only Rs12,000 for building a toilet [under SBM]. We know this is not enough for building a better toilet but what can we do about it?” he added.Yadav claims he took up the issue of insufficient SBM funds with the district authorities many times but he was either told "Rs12,000 is a support from the government” or that “people can pool in some money to make better toilets.”Broken toilets, filthy tanksFor an area to get the ODF status, a government survey must confirm that the baseline demand for toilets there is met and that the menace of open defecation is eradicated, this report says. But Sultanpur’s reality contradicts both the checkpoints.Take the case of Dhanrava village from Kurwar block. A local school, which didn’t want to be named, had interviewed 300 families from the village for a survey in 2018. It found that 60% of the residents defecated in the open because many of these SBM toilets needed repair and several families didn’t have a toilet in the first place.Following the survey, the school representatives had questioned the village pradhan Isharat Khan on the shoddy construction and maintenance of the toilets. “He had assured us he will do something about it but nothing has changed since,” says a teacher from the school on the condition of anonymity.A local school had conducted a survey on the status of toilets in Dhanrava in 2018. Credit: Vimlesh Kumar Pandey 101Reporters’ fieldwork upturned similar results in Dhanrava. The toilets remain mostly unused because either their doors are broken or because they are unhygienic.Tabassum Shaikh from Dhanrava claims that her SBM toilet became “unusable” a year after it was constructed in 2017, forcing her and her family to defecate in the open. She showed us the squalid condition of the toilet - the septic tank was overflowing and let out an unbearable stench.“The pradhan has been assuring us that we will get a new toilet but he’s done nothing so far,” says the science schoolteacher.A woman from the locality interrupted our interview with Shaikh and said, "I have my ration card and Aadhaar card. I have submitted my documents many times yet the pradhan hasn’t built a toilet for my family.” This is Rubina Bano, a homemaker who’s forced to go out in the dark, deep into the fields, to relieve herself.When 101Reporters reached out to Khan, the village pradhan, for comments, he simply said he doesn’t have the funds to repair toilets or build new ones. “If the government doesn’t give us money, what can we do?” he explained his position. He refused to take further questions, including how many families in Dhanavar don’t have toilets. He even tried to dissuade this reporter from clicking photographs of the toilets in the area.Case of missing doorsThe institutional apathy is on full display at Pure Gajadhar Tiwari, a village 15 kilometres away from Dhanrava, but so are the signs of desperation.A ‘curtain’ of gunny bags stands in place of a door outside the toilet built for Shashi Vinod Tripathi’s family. "I know the pradhan will not repair [the broken door] and I don't have money to buy a new door for the toilet. So I hung the bori [gunny bags]. What’s the point of installing weak doors?” asks Tripathi, who works as a labourer.A homemaker named Kausilya Tiwari claims she has spent Rs2,200 to add a new door to her SBM toilet. "I had approached pradhan and even the Block Development Committee for a new door but my requests went unheard,” the 32-year-old homemaker explains why she took the matter into her hands.Kausilya Tiwari spent Rs2,200 to add a door to her toilet when the pradhan failed to. Credit: Bilal A KhanFour kilometres away, in the village of Kanupur, a couple of toilets stand without doors. This defeats the vision of Swachh Bharat Mission, which aims to provide privacy and calls these toilets Izzat Ghar (House of dignity).Anita Biskarma has one such doorless toilet. The village pradhan died when the toilet was under construction — before the door was installed. “So it remains unused,” says the homemaker.Radhe Shyam Yadav, the current pradhan of Kanupur said that he is not responsible for what the previous pradhan did or did not do for the village. "He had finalised the toilets. He is the only one to tell why doors were not attached," Yadav argues.No commentsDilapidated toilets, cashless pradhans and open defecation, 101Reporters witnessed this in other villages of Sultanpur too. So can the district or the state of Uttar Pradesh claim itself to be free of open defecation?This 101Reporters' reporter visited the district magistrate Raveesh Gupta on three occasions to seek an explanation but he was either unavailable or busy to comment.Local MLA Abrar Ahmed refused to meet us in person. He did come on a call only to talk about the development work he had done in these villages while ducking the questions related to SBM toilets.“If the state government will do an authentic survey on this [matter], local pradhans will be in trouble. Many villages in Sultanpur are not Open Defecation Free,” Wakeel Ahmed, a resident from Dhanrava, tells us mockingly.His remark is not far-fetched. Multiple studies have cast doubts on Modi government’s claim of achieving nearly 100 per cent toilet coverage under the Swachh Bharat Mission. Not every household in the states of Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh has an exclusive toilet, the same report goes on to write.

Govt's welfare schemes fail to reach the differently abled in Mumbai

Mumbai, Maharashtra: Even though Maharashtra has 11% of the country’s differently-abled population, the administration has failed to extend services and schemes to the community, say representative bodies. In the absence of support from the government, survival for the differently abled becomes difficult as a majority of them are unemployed. Experts point out that the differently abled are usually underpaid by the companies. They add that a majority of them are also unable to access welfare schemes of the government.Arun Mayavan, founder of Ashish Foundation, a Mumbai-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) working for the empowerment of the differently abled, stated that private companies tend not to give jobs to the differently abled on terms previously agreed upon. He alleged that many companies underpay them for working the same as anybody else. He claimed that even he was underpaid at his former job, prompting him to quit.Arun Mayavan, founder of Ashish Foundation. Credits: Bilal A khanMayavan added that the political parties don’t deliver on their promises after getting elected. “The private companies belittle us by paying less salary and making differently abled people do different work from they were promised,” he commented.Struggle with the system Apart from the social stigma and isolation, the community members state that they are frustrated with the system. From getting disability certificates to acquiring self-employment (livelihood) facilities through government funds to pensions and other facilities by the government can be quite harrowing, they claim. Junaid Ansari, 23, a resident of Govandi, stated that even after completing his 12th examinations and industrial training, he has been trying to get a scooter, under a state government scheme, for over two years now.“I submitted every document but I am always sent home saying I will receive a call once the scooter is assigned. It’s been two years now. How long should I wait now,” asked Junaid. He also pointed out that despite having the required qualifications, many companies reject him because he can only type with one hand. “Based on my experience and people I know, I don't think I’ll ever be able to find a job based on knowledge,” added Junaid.However, even beneficiaries of the schemes claim that the quality of products, be it a photocopier or scooter, is sub-par. Nadeem Shaikh, 40, a resident of Mumbai's Mankhurd area, stated that he received a photocopier from the state government but it stopped working within three months. When he brought it up with the concerned municipal ward office, they ignored his requests, he added. He said he tried to get it repaired multiple times, but it would break down again soon after. Speaking to 101Reporters, Bhaskar Jadhav, community development officer, Municipal Corporation Of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), mentioned that there was a limited budget, Rs 3 crore for photocopiers and Rs 4 crore for scooters, in the current fiscal year. He informed that though there were 896 eligible beneficiaries for the scooter scheme, they have been able to provide it to 400 people so far. For the photocopier scheme, they were only able to distribute the machines to 263 people out of the 600 eligible people. He stated that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the scheme, and owing to the lack of funds, they are not able to meet their targets.He pointed out that according to the 2015 survey by MCGM's health department, there are more than 57,800 differently abled people across Mumbai, but he believes the data is not precise. To correct this, the MCGM is going to conduct another survey which will give them a better understanding, he added.Red-tape hurdlesIrfan Ali Khan, a member of Apnalaya, an NGO working to empower the urban poor, stated that many differently abled people have been forced to visit government offices multiple times for their hearing machines, pensions and other welfare schemes, but end up returning home without anything. Khan, who himself is differently abled, stated that he feels frustrated when he is forced to visit government offices multiple times and has to return empty-handed. Nadeem echoed similar concerns. He stated that he had to run around a lot to get a photocopier. “Despite having all the documents, which include disability certificate, PAN card and Aadhaar card, we are asked to visit corporators, then collector and different municipal officials for stamps. They don’t understand that we are handicapped. We can’t run from pillar to post,” he added. In 2018, the Maharashtra government digitised the process of applying for disability certificates. One needs to have address proof, identity proof and details of employment. Many people allege that they had to wait for more than six months to get their disability certificates.Sandesh Durguli, a resident of Sion area, stated that he received his disability certificate after seven months during which time he had to visit several municipal officials multiple times. Ashish Foundation’s Mayavan stated that he has seen many people who have had to wait for a year to get their disability certificates. Instead of easing the process, the online system has made the procedure more time-consuming, he claimed. However, MCGM’s Jadhav stated that the delay is because of the time they need to verify the applications. Even in case of schemes, he said they process the application and distribute the benefits after due process is followed.

In UP's Sultanpur district, it's all work and no pay for MNREGA workers

Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh: While the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) was introduced to provide employment in rural areas, residents of Mairi Sangram village in Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh say they have received partial or no payment for the work they have done.According to media reports, there are 57.13 lakh workers employed under the MGNREGA in UP. Reports also say that the state employs the most people under the scheme in the country and increased the daily wage from Rs 182 to Rs 202. The residents claim that despite working from April to June this year to dig a pond under the harsh sun, they were not paid for their work.Rajendra Kumar and Sudama, who are unrelated, use the same job card. Official records show they have worked for 12 days under the MGNREGA scheme, but haven’t received any money as wages.Sudama stated she keeps requesting the de facto village head (pradhan) to credit the amount due to them to their bank account, to which he says they have already received the amount. “We gave our blood and sweat while working, but our hard work has gone into vain. It’s been months, but I haven't received the money for my work. I visit the bank to check the balance every week,” said Sudama. Sudama has to support a family of six, where she is the only earning member after her son lost his job as a security guard at a private company during the pandemic. Ram Kumar Rawat stated he worked for 44 days under the MGNREGA scheme where they helped dig a pond in the village. However, according to the official data he has only been paid for 28 days. He has four family members to look after and he is the sole earning member. Whenever he approaches the acting pradhan to transfer the money to his account, he is asked to be patient, he claimed. Acting pradhan misusing funds: VillagersSeveral villagers also allege that the acting pradhan makes an alternative list where he puts the name of his family members and acquaintances in the list who worked under MGNREGA and redirects the money meant for others. Several people also allege that the actual sarpanch of the village works as a domestic help at the pradhan's house. “The acting pradhan mentions the names of his friends and relatives. There are many in the village who received about Rs 10,000 [under MGNREGA] but haven't worked a single day,” alleged Ram Jiywan, 50, who works as a tailor in the village. Another villager Chaudheri Prasad Yadav worked for 30 days under the scheme but was only paid for 12 days. He claimed that once he was clicking pictures for proof of the people working under MGNREGA in the pond digging. However, the acting pradhan asked him not to click pictures, he alleged. The village Block Development Committee representative Jay Prakash Yadav also confirmed the allegation by the villagers. Speaking to 101Reporters, he mentioned that the people who have worked under the MGNREGA scheme have been paid either little or no money.A villager showing how they survive with little money. Credits: Bilal A. KhanHinting towards the misappropriating of funds by the acting pradhan, Yadav asserted, “I know what’s happening in the village and who is doing what. I know about the corruption going on in the village.”When asked if he has filed a complaint with his seniors, he says that since the acting pradhan is influential and politically connected, it could be dangerous for him to file an official complaint. However, the acting pradhan Sanjay Shukla rubbished all the claims. He asserted that he hasn’t indulged in any corruption and has sent the list to the department concerned to transfer the money to the account of the due beneficiaries. Despite making repeated calls to the state labour department, the reporter received no response. Sitaram Verma, Bharatiya Janata Party MLA from the constituency, stated he didn't know anything about the matter and assured that he would look into it. The District Magistrate said he was unaware of the issue and hadn't received any complaint in this regard.

.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Write For 101Reporters

Follow Us On

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All News