Tamil Nadu’s curious case of queuing up for free farm power, slow subsidised solar transition

It may take years before all applicants get free agricultural service connections from the state government, yet there is only a mild response to the Centre’s PM-KUSUM solar scheme Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu: Giving a gap-toothed smile, Malarkodi Subramaniam (50) of Kollangarai Vallundanpattu in Thanjavur district poses before her brand new solar panels, which to use her own words is a “divine blessing”. Up until eight months ago, she struggled operating an oil motor to water her groundnut crop on three acres of land.“Fixing the flywheel back to the pump when it gets disconnected is quite a task. To reconnect it, I have to seek assistance from those in the nearby fields. The struggle was such that I had to make multiple trips between the field and the motor shed throughout the day to rotate the flywheel manually and operate the motor,” she recalls. After several years of daily drudgery, relief came when she decided to get a solar pump from a private dealer. She is eligible for the free power supply that the Tamil Nadu government provides to farmers, but is unable to apply due to patta (land title) related issues. So, she had no option but to buy a solar pump worth around Rs 70,000 using her hard-earned savings. She could have applied for a subsidised solar pump under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM), but lack of awareness about the scheme posed a hurdle.Having completed her first round of groundnut harvest profitably after the solar switch, she has decided to cultivate the crop again. “I can pump sufficient water into the fields now. Relying on a diesel motor would not have yielded such a success,” she beams. In the same village, Panchamoorthy Veeraiyan (52) still runs a diesel motor to irrigate his 1.5-acre field. "Input cost for paddy comes to Rs 40,000, while diesel costs Rs 25,000 and motor maintenance Rs 15,000. Labour costs add up to Rs 20,000. In short, my net income after 100 days of hard work is just around Rs 20,000," he laments.Panchamoorthy Veeraiyan is planning to switch to solar pumps (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)The increasing financial burden indicates the preference for free agricultural service connections. Over 23 lakh free connections have been provided so far, including one lakh connections in 2021-22 and 50,000 in 2022-23, under the scheme launched in the 1990s. Around four lakh applications are still pending. At the same time, the cost of keeping electricity free is adding up for the Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation (TANGEDCO) and the state government. As per the 2023-24 policy note, Rs 7,857.76 crore was dedicated for free power until 2022-23. The connections are given on a first come, first served basis, but the applicant should own at least half an acre of land with a functional well or bore well. “I cultivate only a few vegetables in my small piece of land. We lack the financial means to purchase additional land just to avail of free power,” says Palaniappan Muthaiyan (43) of Vengarayan Kudikadu.Sundar Raj V (47) of the same village registered for agricultural service connection in 2019. “Considering the demand, I am sure it will take another five years before I receive the connection. Waiting that long for basic electricity is simply not feasible,” he says.In such a situation, solar-powered pumps could have been a game changer. However, the pace of its uptake has been painstakingly slow in the state.Sundar Raj is still waiting for free electricity connection since he registered in 2019 (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)Low patronageAs per a study report, Tamil Nadu has close to 12,000 villages in 32 districts, with a majority of the districts witnessing year-round cultivation of paddy, sugarcane, maize, groundnut, etc. While some areas, particularly the catchment area of the Cauvery, are served by canal irrigation, several areas are solely dependent on rainfall and groundwater. Consequently, Tamil Nadu has an installed base of over two lakh agricultural pumps, amongst the largest in India.Ganapathy Murugaiyan (50) lacks funds to fully utilise the abundant water resource of Vengarayan Kudikadu for a good harvest. “Currently, we can only harvest if we have the financial means to water the crops. Hence, solar pumps offer a promising solution, ensuring water availability whenever the sun shines, regardless of our financial situation,” he says.(Above)Ganapathy Murugaiyan uses diesel motor for his field (below) Vaithiyalingam Duraikannu calls for accessible subsidies (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)However, Vaithiyalingam Duraikannu, chairman, Rain-fed Region Farmers Association, Thanjavur, feels that those who already have access to free electricity are unlikely to transition to solar power because they benefit from 24x7 power availability.Though PM-KUSUM with three components seems promising, Martin Scherfler, co-founder, Auroville Consulting, tells 101Reporters that the scheme has not really taken off. “The one that has seen some numbers is PM-KUSUM’s component-B,” he claims. Auroville Consulting collaborates with various national and international institutions and governments to develop sustainable industrial development policies and technologies.Component-A of PM-KUSUM involves establishment of decentralised solar plants on farmlands by an individual or a group of farmers/cooperatives/panchayats/farmer producer organisations, with a capacity totalling 10,000 MW. The power generated will be purchased by a local discom at a pre-fixed tariff. Component-B is for installing stand-alone solar agriculture pumps of up to 7.5 HP capacity by individual farmers, while component-C is for solarisation of grid-connected agriculture pumps. The farmer can sell the excess power generated under component-C to discoms at a pre-fixed tariff.Grants of 30% each from the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy and state government would be provided under components A and C. The farmer needs to invest the remaining 40%. “For component-B, 40% subsidy comes from the Centre and 30% from the state. The remaining has to be borne by the farmers. For guidance, they may approach the Agricultural Engineering Department in their district,” informs Ramesh Desikan, Head of Department, Renewable Energy, Tamil Nadu Agriculture University.But farmers are not impressed. “Earlier, it was mentioned that the Agriculture Department provides subsidies, but it seems unreliable. Even my friends installed solar pumps using their own funds,” claims Murugaiyan. “If we opt for the subsidy route, there is a possibility that we may not receive it immediately,” adds Veeraiyan.Such misconceptions have reflected on the patronage of PM-KUSUM in Tamil Nadu. While the total sanctioned solar capacity in the state is 424 MW under component-A, not a single solar pump has been installed. For component-B, sanctioned capacity is 5,200 MW and installed capacity 3,187 MW. Under component-C, neither individual pump solar nor feeder level solar capacity has been sanctioned or installed. As farmers are always in debt, Anand Prabu Pathanjali, partnerships and campaigns manager, Power for All, a global network campaigning for distributed renewable energy, insists that having less burden from another technology component like solar pump is crucial for farmers. He adds that a government push is needed for solar pump adoption, especially as the scheme is already being run since 2019 and would be available only till 2026. Palaniappan cultivates only vegetables as he cannot afford the water intensive crops using his present diesel pumps (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)Entangled in debtOne of the best outcomes of an increased patronage of PM-KUSUM in Tamil Nadu could be the opportunity to bail out TANGEDCO from its debt crisis. “TANGEDCO bears an annual cost of roughly Rs 6,000 crore to cater to the agriculture sector, one of the biggest consumers of electricity or free electricity,” says Pathanjali.Scherfler states that the state government covers half the expenses incurred in providing free electricity, but does not always pay on time. “The remaining 50% is typically recuperated from industrial and commercial sectors through higher tariffs. However, many of these consumers have opted to generate their own renewable energy, making TANGEDCO face significant losses,” he explains.Being a state-owned public sector undertaking, the government keeps bailing out TANGEDCO every few years. “The money for bailing out is our tax money… and we are paying even the interest on that debt,” Scherfler reminds, adding that TANGEDCO’s total outstanding debt was around Rs 1,20,000 crore last year. Pathanjali believes that PM-KUSUM component-C has the ability to reduce dependence on agriculture service connections. Farmers will be using solar pumps for agriculture for around six months in a year. The rest of the year, they can export the produced electricity to the grid. “If money comes to farmers by exporting electricity to the grid, it would certainly improve their livelihood and rural economy in a far better way than a subsidy and free electricity,” he notes.However, Scherfler argues that the surplus exported to the grid would most likely not be sufficient to recover the farmer’s 40% investment.As they were not consulted while designing the scheme, farmers think that electricity meters would be introduced for component-C. “The introduction of meters is seen as a direct approach of introducing electricity tariff, which means doing away with free electricity,” says Scherfler, from his decade-long experience in energy consultancy.Explaining further, Sundar Raj says the government has already introduced a scheme where they instal a meter for electricity, allowing selling of surplus energy to the grid. “While the meter tracks energy use and production, they may purchase surplus energy initially, but may later charge us for the energy produced in our systems. So, many farmers view this scheme as unbeneficial,” he says.Knowing well that the farmers will not be interested in solar pumps when they get free electricity, the Tamil Nadu model of PM-KUSUM component-C was designed in such a way that a developer will build a solar plant on the land rented from the farmer. For every kilowatt hour (kWh) of solar power consumed by the farmer or exported, TANGEDCO will pay Rs 3 to 4 to the developer, according to Scherfler.Since TANGEDCO spends about Rs 9 to supply 1kWh of power to the farmer under the free electricity scheme, there is a straightaway reduction of Rs 5 if the supply is from the farmer’s land itself. “It is a viable model because it is much cheaper to produce electricity on the farm,” says Scherfler, adding that the scheme was never implemented in Tamil Nadu. “I think there was a perception within the decision-makers that farmers would not accept it,” he says, adding that it was a political decision as farmers formed a large vote bank. Edited by Rekha PulinnoliCover Photo - Malarkodi shifted to solar pumps and found them beneficial (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)This story has been produced by the author with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

-11.webp&w=3840&q=75)

‘If they are least bothered about our drinking water, why offer faeces-powered biogas for cooking?’

Residents of Kamaraj Nagar believe that Coimbatore Corporation imposed the community kitchen project on them, which led to its closure in no timeCoimbatore, Tamil Nadu: When a community kitchen powered by biogas from human excreta was introduced in Kamaraj Nagar colony of Edayarpalayam in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore district, some eyebrows were naturally raised. For many, the idea of using cooking fuel generated from faeces accumulating in a nearby public toilet’s septic tank was implausible, if not disgusting.Opened in June 2014 with 16 stoves, the community kitchen functioned only for less than a month as women of this Scheduled Caste colony complained of foul smell and itching, and showed revulsion towards it. The project worth Rs 17.80 lakh was expected to serve around 73 families, and most of them did make use of the facility for a day or two. However, it did not pan out the way the Coimbatore Corporation wanted it to be.Asked why she did not utilise the free biogas, Rani* retorted, “Are we not humans? Why should we cook with biogas produced from human excreta? After taking a bath in the water boiled in that kitchen, I experienced itching. Even our food carried that unpleasant odour. It is reminiscent of a septic tank.” Savitha*, another colony resident, refuted her neighbour’s claim, suggesting it was more of a mental inhibition and awkwardness, besides a case of spreading unfounded rumours. However, she did admit, “There was no foul smell initially, but it became unbearable within a few days. Yet, I continued to cook there as long as the kitchen was functional because it significantly reduced my cooking time."Ever since the kitchen’s closure, Savitha and others have switched back to firewood use. As LPG is very unaffordable, they try to minimise its use. Any dish with a longer cooking time is prepared using firewood. “When the kitchen was started, I felt a sense of hope and relief. However, all that was short-lived,” Savitha said, adding that drunkards took advantage of the situation and stole the burners, stoves and other equipment.“Empty bottles of alcohol and leftover food make the place dirty and unpleasant. We reported the issue to the councillor, but there was no follow-up action,” she claimed.Opened in June 2014 with 16 stoves, the community kitchen functioned only for less than a month (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)Who killed the project?According to local resident Senthil*, the plant still produced biogas. “If we turn on the regulator, we can sense it. But what is the purpose if the community kitchen is not functional?” The corporation claimed the kitchen became inoperative because people did not want it. “They complained of foul smell. We will not reopen it as that would be against the people’s wishes,” Sakthivel, Corporation Officer, West Zone, Coimbatore, told 101Reporters. Elaborating how the project as a whole was perceived as lacking in value, Karamallayan, General Manager (in-charge), Tamilnadu Energy Development Agency, told 101Reporters that it was not just the biogas from faeces that people viewed unfavourably. “For instance, there is a biogas plant on a temple premises in Chennai to utilise temple waste such as flowers. However, even that plant was shut as people perceived it as a by-product of waste.”He emphasised that the first and foremost step to ensure continuous operation of biogas plants was to raise awareness within the communities.Explaining the science behind the biogas odour, Desikan Ramesh, Professor and Head of Renewable Energy, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, said, “Microorganisms in the septic tank break down faecal matter. When cleaning solutions that inhibit growth of good bacteria are used, this process is disturbed, leading to foul smell from the biogas produced. So, due care should be taken while selecting toilet cleaners.” Asked about the theft of community kitchen equipment, Sakthivel said he had no idea if any action had been taken as he was posted in Edayarpalayam only a year ago. “The corporation commissioner, mayor and councillor attended the inauguration of the community kitchen. That was it. After that no corporation or local body official took time to review the project," Rani blamed. (Above) The public toilets in Kamaraj Nagar colony of Edayarpalayam; (below) The biogas input area behind the toilets has become a dump yard for waste materials (Photos - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)Setting wrong prioritiesEdayarpalayam panchayat became a part of the municipal corporation of Coimbatore a decade ago. People of the colony are mostly involved in informal jobs in the corporation. Women work as housemaids in nearby residential areas. They live in houses with only one or two rooms, and lacking in proper upkeep. The children of the households are mostly uneducated or have limited educational backgrounds. According to Savitha, their concerns were heard when they were under the panchayat. “As members of an oppressed caste, we are always ignored. Local body officials come calling only during elections.” Echoing her, Senthil said, “No one asked us about our needs. They imposed this project on us without any consultation. When it rains, our houses get submerged in knee-deep sewage polluted water. We have to use motors to pump it out. Else, we will remain stranded," he added. Problems do not end there. Senthil cited the case of their water tank, which has developed a big crack. “It is on the verge of collapse. Neither repairs happened nor at least a show of concern from the official side. If they are least bothered about our drinking water, why offer biogas for cooking? It seems our basic needs and safety are being overlooked,” he stated.Savitha also shared about other pressing concerns of the community. "For us, addressing our basic necessities is far more important than the biogas project. Our houses are on the verge of collapse, yet we have not been granted land titles (pattas) for the small plots we inhabit. Without land titles, we are unable to access loans or government schemes.” “It is ironic that we continue to pay house taxes to the corporation, which are higher than what we used to pay under the panchayat. When we lack proper shelter, the value of biogas diminishes in our lives,” she added.Rani was equally vocal while listing out the needs. “Clearing out bushes and shrubs from our residential area should be the first priority as snakes enter our homes quite often. We live in constant fear every day, especially with our children around. Our safety is at stake, and we are desperately in need of a secure environment."Speaking anonymously on behalf of the children in the community, a child shared, "We lack basic amenities and do not have a safe space to play. We are not allowed to play outside due to the presence of snakes and alcoholics, besides poor sanitation. It is a difficult and restricted environment for us."Thirumal, Zonal Sanitation Officer, West Zone, Coimbatore Corporation, denied the presence of snakes and other sanitation issues, but assured that suitable action will follow after site inspection. However, the residents argued, “Even yesterday, snakes entered our homes.” A plack commemorating the biogas community kitchen; Residents say they had more urgent needs — the drinking water tank (behind the tree) is in dire need of repairs and waste is not collected from their homes (Photos - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)More construction on the wayA year ago, the community kitchen was converted into an office of the corporation to register the attendance of sanitation workers. “People did not use the kitchen, which is why it has been repurposed. No one has so far approached us seeking the kitchen’s revival. If people need it, we will work on that,” assured Tamilselvan P, corporation councillor, Edayarpalayam. Several officials of the Coimbatore Corporation did not respond to queries about the project closure, stating that they were new to the office and were not aware of the details. Meanwhile, Rani expressed her frustration with the functioning of the civic body. "It has become a habit of the corporation to impose projects on us without seeking our consent. Currently, they are constructing a primary healthcare facility near the community kitchen building. We do not want that. Now, medical wastes will be dumped on us, exacerbating the existing waste issue. Instead of community kitchens or hospitals, what we truly need is access to clean water, improved sanitation and proper shelter," she summed up.*Names changed to protect privacyEdited by Rekha PulinnoliCover photo - A year ago, the community kitchen was converted into an office for the corporation to coordinate with local sanitation workers (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam, 101Reporters)

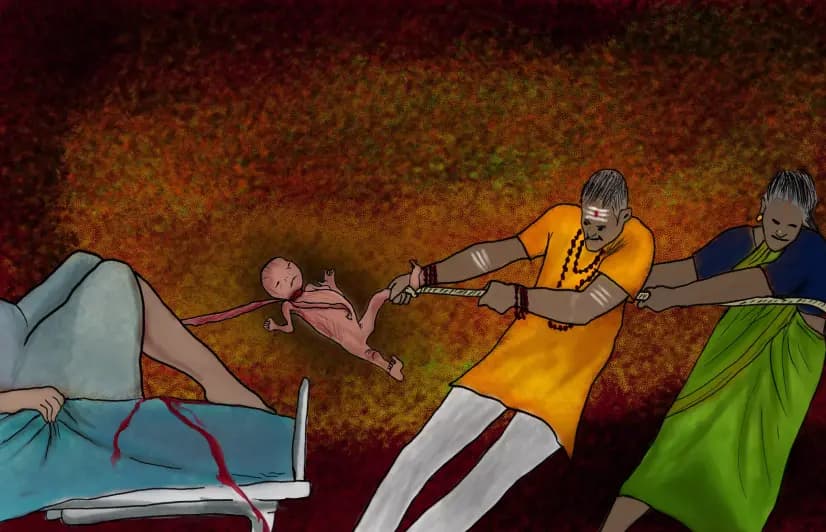

Tamil mothers forced to risk health of new babies to avoid 'inauspicious months'

Families push for induced labour or elective C-section to avoid ‘inauspicious’ Tamil months of aadi and chithirai, but seldom understand the risk that such acts pose to the lives of both mother and child Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: When Valli* came home after a complicated delivery in 2016, her family blamed her baby boy for “terrifying them during his birth”.“Nobody realised the trauma he went through because they forced his delivery!” wept Valli, whose nurse-mother had coerced the gynaecologist to artificially induce labour at 36 weeks because she did not want her grandchild to be born in an ‘inauspicious’ month. Valli had conceived after battling with polycystic ovary syndrome for two years, but when she shared the good news, her mother was quite cryptic. “That means the baby will come in chithirai month!” she remarked. Chithirai (March-April) heralds the Tamil New Year, but many families believe that a birth in that month would essentially mean difficulties in future life. And thus began Valli’s trauma. “My mother kept asking me if I wanted to give a troubled life to my child. I knew that was absurd, but I was not emotionally fit to think critically. I was afraid people would blame my baby if anything went wrong in future. That fact really affected me.”Since her mother had earlier worked as a nurse in the same hospital where Valli was consulting, she convinced the doctor for a delivery before chithirai, though the due date was May 15. “The baby did not descend easily as labour was induced artificially. My cervix failed to efface and became hard as a rim. The baby also developed a scalp swelling (Caput succedaneum) due to repeated forced contractions,” said Valli, who had been a nurse in the same hospital.As she was averse to the idea of a Caesarean delivery (C-section), the gynaecologist supported her in a vaginal birth by manually dilating the cervix from six cm to 10 cm. That led to a foetal distress and a sudden heart rate drop between 40 to 60 bpm against the normal 140 to 160 bpm. “Separated just by a screen was another woman delivering her dead foetus. I could hear everything happening there. That doctor even shouted at my nurses to shift me for an emergency C-section as my baby had Bradycardia (slow heart rate) and no pulse… By that time, my gynaecologist had gone to attend to another woman who opted for a C-section due to a medical condition similar to mine,” Valli recounted everything that went wrong around her. “I had flashbacks of my previous miscarriage, failed fertility treatments, and the long wait for conception. What if I lose this baby too? I kept talking to the baby expressing my love,” said Valli.It was nothing short of a miracle to her when the doctor came back and extracted her baby vaginally using forceps. “The baby had mild breathing issues and was kept in the neonatal intensive care unit for the first few hours,” she said.Months of ‘peril’Risky births are becoming common in the days leading up to the months of chithirai and aadi (June-July). Nalini* of Erode was to give birth during aadi in 2018, but her family cited examples of aadi-born people who did not do well in life. As if to add fuel to fire, an astrologer had told the family that she would deliver a baby boy, but the birth in aadi would be most inauspicious.“I did not worry much until my mother asked the gynaecologist if I can be put through an elective C-section 20 days prior to the due date. I was taken aback. I felt so bad that nobody even required my consent,” Nalini told 101Reporters. Luckily, for Nalini, her doctor did not yield, but patiently explained to my mother about foetal development and the need to go full-term.” Despite that, Nalini underwent an emergency C-section, which she believed was the result of the negative environment that the people around her had created. While the State government does not share data on monthly delivery caseload, the maternal healthcare infrastructure remains practically overburdened during chithirai and aadi. It was during the 38th-week check-up of Hasini* that her mother-in-law pleaded to the doctor to prepone her delivery to avoid aadi. “The doctor did not heed due to slot unavailability. She said I will have to wait for another week for C-section.”“But my mother-in-law persisted and there I was, waiting till 9 pm in the hall to get a room for delivery the next morning. Meanwhile, my family tried to convince me to opt for an induced birth. Apparently, they were more worried about the possible delays in C-section procedure as the hospital had a high caseload preceding aadi. But I remained adamant… Despite a sleepless night, my baby was born healthy. But we remained separated for four hours straight. I was not moved to the room even two hours after my anaesthesia wore off as the hospital staff were too busy.”An Erode-based anganwadi worker who has been monitoring and assisting pregnant women for over two decades shared on the condition of anonymity that around 20% of expectant mothers in her area went for elective C-sections to avoid aadi and chithirai. "No one understands the risks!" Busting the myths, medicallyIn her over 30 years of medical practice in Coimbatore, Dr Saraswathi has lost patients for not agreeing to preterm deliveries. “I may lose my income, but not my sleep,” said the obstetrician-gynaecologist whom Nalini had consulted.She noted that families often compromise a woman’s right to her body by misusing her state of emotional vulnerability, driven by hormonal imbalance. “Uterus prepares for labour from the 37th week. So why should we interfere in this natural process? Moreover, C-section is a live-saving procedure that should only be performed for the right reasons.”Kanimozhi Senthamarai Kannan, a lactation consultant in Coimbatore, told 101Reporters that induced birth or elective C-section can lead to severe lactation issues. “After the placenta is delivered, the body receives a cue that the baby is born and it starts secreting milk. In the case of scheduled birthing, the body will take time to realise that the birthing is over, which affects immediate breastfeeding.”“Women going through scheduled births face breastfeeding issues and have to depend on baby formulas. Most C-section borns also do not get immediate skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding in the first hour of birthing due to NICU admissions. Both lead to breastfeeding obstacles such as improper latching, sucking, breast refusal and respiratory distress, besides leaving a difficult blotch for mothers to cope with.”Dr Karthick Annamalai, a paediatrician and neonatologist in Coimbatore, told 101Reporters that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists defined 39 to 40 weeks as full-term, 37-38 weeks as early-term, and 34-36 weeks as a late preterm. “During the scan in 35-36 weeks, some babies are found to have gained weight. Families misunderstand weight for maturity and request for C-section. But they do not understand the importance of the baby's last month in the womb.” He said a baby born at 28 weeks as a result of spontaneous preterm labour would be healthier than an elective C-section at 36 weeks because naturally released stress hormones result in higher cortisol levels, thereby maturing the lungs and brain of a foetus. “Baby receives oxygen from the placenta inside the womb. The lungs start functioning only after the baby cries after parturition. This transition to extrauterine life is difficult, especially when babies are forced. In cases when the lungs are still wet, it calls for an NICU admission. Complete liver development is also not promised in preterm babies, putting them at a grave risk of jaundice.” “For a healthy brain and emotional well-being, babies require a naturally safe environment like a mother’s womb or lap. Studies have suggested that preterm babies may have lower IQ levels.” He further threw light on how the medical fraternity avoided legal consequences by not indicating the procedure as ‘elective’. “They mask it with some health indicators.”“Deliveries in the 34th week are the most common during aadi or chithirai, especially if that is twin or IVF pregnancies. Since both these cases are riskier, and IVF treatments cost a fortune, families are more insecure of births in aadi or chithirai,” said Dr Annamalai. Revealing that even margazhi (December-January) has become inauspicious of late, he said he did come across several such cases last month.Dr Pradeep V Krishnakumar, City Health Office, Coimbatore, admitted that familial or social pressure was behind elective C-sections. "Unlike private hospitals, such incidents are rare in government hospitals or Primary Health Centres. We always strive to increase the number of normal deliveries in government hospitals."Summing up, Dr Annamalai said, “the good day for a birth has to be whenever the baby decides to meet the world.” *Names changed to protect the identities of the individualsCover Illustration by Prajwal MEdited by Khwaish Gupta

How biogas-fuelled community kitchen in Kurudampalayam failed to cook up a success story

The project wound up within a year as women preferred the privacy of their home kitchens than the free biogas at the panchayat facility Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: Saraswathi (56) of Kurudampalayam in Coimbatore district had never used the community kitchen when it was operational in 2016. Run by the biogas technology of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), the project stopped functioning in a year’s time due to lack of patronage and issues in maintenance. “Only my husband and I live here. All our children are married. An LPG cylinder would last over four months. Instead of carrying every ingredient to cook meals from my house to the community kitchen, I preferred to purchase firewood for a few rupees. Anyway, it cost much less than an LPG cylinder,” she said.Though the plant was revived last month, after its closure in 2017, the community kitchen is still not back in operation. And even if it is reopened, Saraswathi said she would depend on it only when she ran out of LPG. Saraswathi (56) of Kurudampalayam in Coimbatore district had never used the community kitchen when it was operational in 2016. Even now, when it has been revived, she would depend on it only if she ran out of LPG (Photo: Gowthami Subramaniam)Based on the BARC’s Nisargruna plant, the community kitchen was equipped with 21 stoves to cook food free of cost; yet a fraction were actually used. “The District Rural Development Agency (DRDA) implemented the project in our panchayat with BARC funds worth Rs 30 lakh. Additionally, the district collector donated Rs 10 lakh for building the kitchen. The BARC also did Nisargruna technology transfer to make the project a reality,” Kurudampalayam panchayat president D Ravi explained.Every day, the plant could process two tonnes of organic waste, but only a few families utilised the biogas produced. Goat herder R Kaliammal (67), one of the beneficiaries, has a big family, which means she also has high food and fuel costs. “I now spend nearly two hours collecting firewood from the forest. When it rains, I have to sun-dry it too. In such a situation, I have to resort to an LPG cylinder,” she said. Reminiscing how things were easy when the community kitchen was functional, Kaliammal said, “My daughter-in-law and I would take the required vegetables, rice and pulses from our home and cook every day at the community kitchen. It saved us the time and effort required for collecting firewood,” said Kaliammal. Thulasimani (45), who lived close to the community kitchen, accessed it regularly. “The street is long and extends further to the north. For those located at a distance, carrying all the ingredients and vessels from their homes seemed unfeasible. Eventually, they stopped using the facility.”However, the rising LPG price is a concern for Thulasimani’s family of five. “An LPG cylinder costs Rs 1,110, and it does not even last for 45 days!”A polygonal view of the biogas plant (Photo: Gowthami Subramaniam)The panchayat stalemateA promising endeavour to make a fortune out of solid wastes, the community kitchen project failed as the few women who cooked there did so only once a day. “The young ladies felt shy, and only older women accessed it regularly,” mentioned Ravi, who headed a 20-member team that supervised all tasks, from waste segregation to plant operation.Taking note of the low patronage, the panchayat then decided to shift the kitchen to a smaller area next to the biogas plant and began construction for the same. The existing building was repurposed into a community hall in 2016.Pointing to the raised pillars at the site where the new kitchen was proposed, Ravi said they could not complete the construction as “our term got over and the panchayat elections were paused for the next three years.” (Above) The community kitchen, which the Kurudampalayam panchayat had tried to lease out to a women’s canteen or self-help group; (below) the Nisarguna Bio Methanation Plant in Coimbatore (Photos: Gowthami Subramaniam)With the panchayat non-functional from 2016 to 2019, waste segregation also came to a halt. “We used to collect Rs 30 per house under the Swachh Bharat Mission. Besides operating the biogas plant, we made extra money by selling segregated and recycled wastes. This paid the salaries of sanitation and maintenance workers at the plant,” informed Ravi, who got another term as panchayat president following the 2019 polls. Additionally, the panchayat had received corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds for waste segregation and plant operation. “Dimexon Diamonds Ltd Coimbatore & Emerald Jewel Industry offered Rs 24,000 and Rs 40,000 monthly for three consecutive years”, said Ravi. As many as 45 sanitation workers had been engaged to collect segregated waste from 13,000 families in 11 wards, with each worker handling 150 households.Besides generating employment, the activity had kept the panchayat spic and span. Notably, Kurudampalayam is a recipient of the Panchayat Sashasktikaran Puraskar in 2014 and Tamil Nadu government’s Clean Village Campaign award in 2016.(Above) R Kaliammal (67), a goat herder and a beneficiary of biogas, now spends nearly two hours collecting firewood from the forest; (Below) For Thulasimani, the rising LPG price is a concern. She says an LPG cylinder costs Rs 1,110, and does not even last for 45 days (Photos: Gowthami Subramaniam) After the panchayat went defunct, improper municipal waste segregation became a vexing issue, according to biogas plant operator Geetha. “Actually, the raw materials should not even have paper pieces in them.” The BARC website estimates that 400-500 gm of biodegradable waste is generated per person per day. Despite the operational issues, BARC still believes the biogas plants could potentially divert the waste from being left in dumping grounds, further causing health hazards. A DRDA official on condition of anonymity confirmed that the plant workers did not receive salaries during the special officer (block development officer) period, which forced disgruntled workers to leave their jobs. Soon, it became a favourite hangout spot for men to consume alcohol.On the operational issues during the special officer period, Nandhakumar, the general secretary of Thannatchi, an NGO that supports the panchayat in several projects, said, “All of a sudden, a block development officer (BDO) was burdened with the humongous work of many villages, which was previously carried out by several panchayat presidents, vice-presidents and ward members.” Despite repeated attempts, Kurudampalayam BDO refused to comment on the issues, including failure to pay salaries, segregate the waste to continuously operate the biogas fuelled-community kitchen and maintain the biogas plant.Knocking on all doors for revenueIn a bid to maximise biogas utilisation and revenue generation, Kurudampalayam panchayat had tried to lease out the community kitchen to a women’s canteen or self-help group. It had also explored the idea of selling biogas to bakeries and restaurants, but all those efforts had failed to gather momentum.“Snacks are prepared daily on high flame. But the biogas pressure was simply not sufficient for us. Hence, we switched back to commercial LPG,” said a bakery owner on condition of anonymity. He had accessed the free biogas for a while. Chythenyan, a research associate at the Centre for Financial Accountability, said “Low Pressure for flame is a common problem with biogas as it contains some amount of wetness due to water vapour. Hence, a compressor can help the biogas to be supplied at a constant pressure like LPG cylinders”.To promote waste segregation, the panchayat had first offered two free dustbins of Rs 20 each to every household. However, poor response forced them to train all sanitation workers to do the segregation before the waste entered the corporation bins.“We also collected plastic waste separately for Rs 10 per kg from houses and sold it to recycling plants… The biogas slurry was also sold to farmers as an organic fertiliser at a subsidy rate of Rs 10 per kg,” said Ravi.(Above) The alcohol bottles found at the biogas plant; (below) the half-constructed pillars of a small community kitchen that was planned in 2016 (Photos: Gowthami Subramaniam)Though all the measures had generated revenue, it was meagre when compared to the actual needs of the panchayat. “We needed approximately Rs 5 lakh per month to segregate wastes and run the biogas plant. The State government provided only Rs 3,600 per sanitation worker on 27 routes, whereas the actual salary paid was Rs 6,000 on 45 routes from the panchayat money,” said Ravi, citing the deficit.Not just that, the panchayat had been segregating waste from only 11 out of the 15 wards due to fund crunch. “If we were to input the segregated wastes from the entire panchayat to the plant, we would have added another 25 routes with 25 more sanitation workers and supervisors,” he said. Explaining how a top-down approach could render biogas projects defunct after the initial years, Nandhakumar said the government should reflect on the outcome of such schemes or look into the operational hindrances to find a long-term sustainable solution. Admitting that there was a lack of follow-up of old schemes when several projects were being pushed, a State government official, on condition of anonymity, said, “All schemes cover the hard costs of implementation, whereas most schemes only allot little to no funds for maintenance, thus leading to failure of projects.”Expert viewCompressed biogas was an idea that Tamilnadu Energy Development Agency (TEDA) general manager in-charge Karamallayan suggested to make individual households adopt the project. “But it needs a massive decentralised plant to bottle biogas, which will incur a huge cost,” he said.Chythenyan suggested a different model to maximise biogas utilisation. “A community-owned enterprise fuelled by community-based biogas and benefit-sharing with the public are important aspects. Kurudampalayam community kitchen should be turned into a community canteen that offers food at low rates to the public.”According to the TEDA website, 189 community and toilet-linked biogas plants have been built in Tamil Nadu, but most of them are defunct. “A lot of research has been done on why community biogas plants are not surviving. Maintenance is one major issue,” Karamallayan said.Though TEDA is not operating biogas projects presently, he said the agency is ready to revive the defunct community plants if the government gives its approval.Beginning afreshDespite the huge expenditure involved in the erstwhile biogas plant, Ravi is gung-ho about reviving production. “Though we thought a community kitchen would be a place for women to share knowledge along with food, it failed as they preferred privacy. Now we are searching for an effective solution to fully utilise the biogas, besides hoping for CSR funds and NGO support.”Giving an interesting insight into how the government has shifted away from community-based toilets to individual ones to instil a sense of ownership, Chythenyan said, “Community kitchen model might not work in a progressive State like Tamil Nadu as more and more people lead private lives.”Even as women like Thulasimani felt a community hall was more important as it served the entire village free, Ravi said, “We are also trying to convert the biogas to electricity and sell it to Grid. This will help in generating some revenue for the panchayat. We will keep trying and learn, no matter how many operational issues we encounter. We are determined in our step towards the non-stop operation of the plant. Success is not very far.”Check out this animated video with the highlights of the story (Produced by Gowthami Subramaniam)The cover image is of maintenance work being carried out for the renovation of the biogas plant clicked by Gowthami Subramaniam.Edited by Rekha PulinnoliThis story is supported by Internews' Earth Journalism Network

Kerala has miles to go to make integrated Pokkali lucrative

The Central fund to promote climate resilience is a welcome step, but farmers need support from implementing agencies and timely redressal mechanisms to make the paddy-aquaculture rotational plan a success Ernakulam, Kerala: Once touted as the way forward to deal with the effects of climate change on farming in coastal wetlands of Kerala, the integrated scheme for pokkali paddy and aquaculture has not been as successful as expected.Known locally as oru nellum, oru meenum (One Paddy, One Fish), the project titled ‘Promotion of Integrated Farming System of Kaipad and Pokkali in Coastal Wetlands of Kerala’ utilised the Centre’s National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (NAFCC). Operated through the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) from 2015 to 2019, it was a harbinger of hope for pokkali farmers like Pradeep MK of Kottuvally panchayat in Ernakulam district.Labour and construction issues dogged Pradeep’s first attempt to renovate his farm under the scheme in 2017. For eight months, labour unions prevented the use of a floating JCB for building the peripheral bund, fearing loss of labour. However, Pradeep’s relentless pursuit of a solution got him an order from the district collector permitting machinery for construction. As if the problems were not enough, the 2018 deluge inflicted heavy damage to the bund. He had no option but to wait for another six months — the time he needed to cultivate and harvest pokkali.When Pradeep finally finished construction, the Agency for Development of Aquaculture (ADAK), the NABARD’s local entity, lent him a huge blow. On inspecting the bund, the ADAK officials found a few areas where the stipulated measurements of 2 m height, 1.5 m top width and 5 m bottom width were not met. Result: Pradeep did not get the NAFCC subsidy.“I took a bank loan of Rs 3 lakh and spent another Rs 2 lakh from my pocket,” Pradeep said. When he finally rebuilt the bund, the ADAK diligently told him that the two-year time limit for construction under the project had lapsed!Harvesting pokkali rice, a unique salt-tolerant variety, that is cultivated in coastal wetlands of Kerala (Photo - Gowthami Subramaniam) Pradeep insisted that the delays caused by floods and unions were not his fault, and that the ADAK was very much aware of it. To avail of the subsidy, he had followed the condition that a group with a minimum of five farmers be formed to cultivate pokkali on at least five hectares. “In my group, three belonged to Schedule Caste and the rest were women. The ADAK did not bother to consider these factors,” Pradeep lamented. He said even his pleas to reconsider the subsidy claim were rejected, while adding that the requirements under such schemes should be changed to accommodate marginal farmers. “A group of two to three with two to three hectares under cultivation will be the apt model.”Jayan, the officer-in-charge of aquatic animal health, Kerala fisheries department, said they would recommend a change of rules to reduce the number of group beneficiaries to three and plot size to three hectares while sending proposals for pokkali support schemes to the government in future.Meanwhile, Pradeep’s rebuilt bund appears to be working for now. “My field escaped flooding several times after the new bund came up.” Why bunds are vitalEarthen bunds that serve as embankments are damaged due to seawater ingress in wetlands. The frequency of damage has increased with climate change. A NABARD report had assessed that 5,765 hectares of pokkali fields were unutilised due to bund damage caused by frequent high tides. In any case, high-yielding varieties cannot be cultivated in these wetlands due to soil salinity. Only salt-tolerant pokkali or kaipad paddy, both of which grow tall and can withstand damage when submerged during periods of rising tides, can be adopted. The fact that the sea level in Kerala is rising at a rate of 3.1 to 3.4 mm per year increases the significance of these varieties.The NAFCC’s push for integrated farming could have served farmers well, provided the underlying issues were amicably addressed. Pokkali is cultivated during the less-saline monsoon months (June to October) and shrimp and prawns are raised in the dry months.(Above) The mesh-fitted sluice gates used to regulate water during high and low tides; Aliyas Puthusheri, an integrated farming practitioner, would spend his nights at the temporary shed near the field (below), keeping a careful eye on the water level (Photos - Gowthami Subramaniam) When water is allowed into the fields from October-end to April, shrimp and fish drift in. During low tide, water is let out through the sluice gates fitted with a mesh that stops the aquatic animals from escaping.“I am used to waking up at night to operate sluice gates during high and low tides for the past 15 years,” said Aliyas Puthusheri (68), an integrated farming practitioner from Ezhikkara panchayat in Ernakulam. Pankajakshan (83) gives him company in a temporary shelter near the field, where they stay vigilant to manage the water level.Though Aliyas got a good harvest due to a normal monsoon this year, it is not always guaranteed. “Six months of prawn cultivation secures our livelihood. Otherwise, how can we get past the losses that erratic rains and rising salinity shower on us?” exclaimed Vincent KP alias Vichappan (75), another local farmer.Though the ADAK had received Rs 250 million for integrated farming — the plan was to provide 80% grant to cover field input and infrastructure costs for 300 hectares each of kaipad and pokkali farms — both Aliyas and Vichappan had never heard of the ‘One Paddy, One Rice’ scheme. “Schemes will be there on paper. Nothing reaches us,” bemoaned Aliyas, also the former president of Palliyakal Cooperative Society Bank, Ezhikkara.Vichappan and his wife have been practising pokkali cultivation for nearly seven decades. They had never heard of the ‘One Paddy, One Rice’ scheme (Photos - Gowthami Subramaniam)Competing paddy schemes Did ADAK fail to sensitise farmers about the scheme? While rejecting the notion, Jayan said 65 farmer groups carrying out pokkali cultivation in 360 hectares in Ernakulam and Thrissur districts received 80% subsidy. However, Saritha Mohan, Agriculture Officer, Ezhikkara Krishi Bhavan, and incharge of Kottuvally, suggested that competing paddy schemes could be the reason. “The State government offers several schemes per hectare of paddy: Rs 32,000 under the panchayat scheme, Rs 10,000 for speciality rice, and Rs 1,000 as post-harvest assistance,” she aid. Aliyas acknowledged having received Rs 1 lakh under the panchayat scheme, but claimed he needed at least Rs 3 lakh to prepare the field.This year, over 140 pokkali farmers have received unsecured and interest-free (for the first six months) loans of Rs 25,000, with an upper limit of Rs 1,25,000 per farmer, from the Palliyakkal Cooperative Society Bank. According to the bank's clerical staff Raseena KA, the bank also buys the crop at a “better price” of up to Rs 60 per kg. Paddy labourers are paid Rs 350 per day, and the wages are deducted from the final price paid. These measures also address the issue of cash flow among farmers.MGNREGA and labour shortageAmong the many objectives of the ‘One Paddy, One Fish’ scheme is the generation of 2,64,000 man-days for labourers. However, they are more interested in the less-demanding work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) scheme, which pays Rs 250 a day. Acknowledging that finding labour was a challenging task, Aliyas said pokkali-related works should be a part of the MGNREGA. Vichappan, meanwhile, called for mechanisation.Though women get work in fields, they are paid only Rs 350 a day against the Rs 1,000 given to men. “When it rains well, we get roughly 120 days of work in the fields. For the rest of the year, we catch fish in the backwaters,” said Sadhi Krishnan (68). The maximum output per hectare of pokkali field is only 0.75 tonnes, but the shrimp business saves farmers. Fertilisers are not used as there is a constant inflow and outflow of water and as the rotational organic wastes of paddy and shrimp keep the fields fertile.“I get paid around Rs 1,000 a day because the land preparation work is extremely hard,” said Pankajakshan, whose income provides for his family of five. Agriculture Officer Saritha explained the process. “The field has to be made as a bed with side channels or mounts to allow monsoon rains to wash the salinity off from the topsoil. Later, the land is levelled to keep the saline-heavy soil at the bottom and low-saline soil on top.” (Above) Abdul Jabbar, an NAFCC beneficiary, with Saritha Mohan, Agriculture Officer, Ezhikkara Krishi Bhavan; The 18 lakh subsidy he received, helped Jabbar, among other things, to raise the height of his bund. Pictured below is the new bund, rising two meters above the old one (Photos - Gowthami Subramaniam)Beneficiaries like Abdul Jabbar (72) from Kottuvally are thankful for the ADAK subsidy that helped him construct a two-metre-high bund. “This year, the Vrischika tide was unusually high. But my field was spared,” said Jabbar, who had received Rs 18 lakh as subsidy for the construction that cost Rs 30 lakh totally.For elderly farmers, pokkali is a matter of sentiment. “Why do I need money when I can catch fish from my backwater and grow vegetables on my land,” asked Vichappan, adding that pokkali has been a part of his life for the last 68 years.Aliyas, whose children hold corporate jobs, summed up aptly. “I cannot live without the sound of tides, no matter how difficult this gets.”Edited by Rekha PulinnoliThis story was written and produced as part of a media skills development programme delivered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publishers.

Tamil Nadu farmers up in arms as canal concretisation rears head once again

For over a decade now, farmers in the districts of Erode and Tirupur have been protesting against a proposed government move to concretise the Lower Bhavani Project canal, fearing it will deter groundwater recharge and eventually affect their crops and livelihoods.Erode, Tamil Nadu: “If the canal gets concretised, there won’t be any system for the groundwater to get recharged,” said Ravi, a farmer and former president of the Murungatholuvu panchayat in Tamil Nadu. This is the thrust of the decade-long protests in the state against the government’s attempted upgrade of the Lower Bhavani Project. The 45-year-old has been among the many at the forefront of a movement aimed at stopping this proposed project. He fears that it will lead roughly two lakh farmers and 163 revenue villages along the canal to suffer from a shortage of water for drinking and irrigation. Local residents of Tamil Nadu’s Erode district launched a protest movement in 2013 — Keezh Bhavani Pasana Pathukappu Iyakkam — to prevent the government from lining the 201-km-long Lower Bhavani Project Canal with concrete. The canal irrigates 2,07,000 acres of ayacut land, which is divided into two blocks of 1,03,500 acres that are irrigated one side at a time over the year. When one of these zones gets directly irrigated by the canal water during its turn, the other half gets irrigated indirectly due to seepage through the channel.Ravi estimates that there are more than one crore trees along the 750-km stretch of the canal on either side and along its branches. To understand the biodiversity of the region and measure the environmental impact of the concretisation project through a formal tree count, he had filed a Right to Information (RTI) application, to which the Public Works Department (PWD) had replied saying it had no data on the number or classification of trees here.“We will lose our water permanently in 36 streams, 1.50 lakh borewells and thousands of wells. We will be forced to migrate,” said the former chief of the Attavanai Anumanpalli gram panchayat, Krishnamoorthy.Unending protests Over the course of their fight against the project for over a decade, local residents have registered their opposition through several mediums — from fasts, demonstrations and roadblocks to public campaigns. In 2013, Krishnamoorthy, along with 500 other people and panchayat leaders, even went inside the dry canal near Arachalur to protest against the PWD’s inspection work for the concretisation. Although all the mesh drains and branch canals are heavily damaged, seepage water from the Lower Bhavani Project Canal plays a vital role in fulfilling the water needs of the region. In fact, the concretisation of the Parambikulam Aliyar Project (PAP) has already dried up all the wells, dams, streams and groundwater along the canal, leaving lakhs of farmers devastated, the 60-year-old said.Advocate Esan Murugasamy, who is also a PAP-dependent farmer and founder of Tamilnadu Farmers' Welfare Association that opposes the project, added: “After the concretisation of the PAP, the environment of the area lost its rich biodiversity. Our wells and streams have water only when there’s rainfall.” The advocate further questioned the report submitted by the Mohanakrishnan Committee, which in 2009 recommended that the Bhavani canal receive a concrete lining to prevent the loss of water at the tailend due to seepage. Arguing that the present scientific measure of water efficiency was against environmental science, he pointed out that the capacity of the canal was 2,300 cubic feet, though only 1,600 cubic feet of water was used for irrigation. However, he advised that the proposal be implemented in part, wherein it suggested that maintenance work be taken up where the canals were dilapidated due to anthropogenic activities.On May 27, during a protest organised by the Keezh Bhavani Pasana Pathukappu Iyakkam at the Nathakadaiyur Junction, over 250 farmers said they received sufficient water at the tailend of the canal. This left Govindammal, a 72-year-old farmer, baffled as the officials had claimed that the proposed project was the only way to get water to the people in this region. Here, Janakarajan, water expert and a retired professor from the Madras Institute of Development Studies, suggested a complete prohibition of illegal water tapping for commercial purposes, as the primary step to get water to the tailend. He said authorities should first ascertain the original command area and assess why it was not getting irrigation water. "There is no point in putting concrete and allowing people to steal water," he echoed the views of the protesters.Podaran, a 70-year-old farmer, recalled an event where hundreds of people who lived downstream in Mangalapatti had gathered to thwart the concretisation project. He’s tired that after battling the proposed plan for a decade, it still continues to come up after every election. During an election campaign in 2015, he was among the villagers who handed over a petition in Kangeyam to the then chief minister, J Jayalalithaa. Though the project was stopped due to stiff opposition in the previous reign, Jayalalithaa’s successor Edappadi K Palaniswami was not ready to put an end to the matter. According to Podaran, Palaniswami even denied receiving the petition from them. “Now the government has changed again, but we remain firm in our demand,” he emphasised. “We sacrificed our land for the construction of the Lower Bhavani Project Canal. Why were we not consulted about the concretisation?”Farmers voice their concerns Kathiresan, a 40-year-old farmer from the village of Ayyampalayam, worries that the polluted water from the Cauvery and Noyyal rivers could contaminate their groundwater if it’s not replenished by the water from the irrigation canal.“All of us have agri-loans to pay off. With this being a dry region, we’ll never be able to repay them if we lose our source of groundwater,” he added.Furthermore, during the 2015 drought, Lakshmi spent a significant sum on efforts to keep her coconut trees alive. She worries that after this so-called developmental move, her farm will see no produce and push her further into financial trouble. “It’s not just about us; our cattle will also die without water as we are majorly dependent on groundwater for our drinking water supply,” the 50-year-old said.Similarly, Maheshwari, a 42-year-old farmer, questioned why the government had not desilted the canal in the past 55 years but was proposing its concretisation now. Here, Ravi added that the response to his RTI query didn’t have any record of desilting either. And after spending years in this battle, he is not ready to leave the matter in the hands of governments or politicians alone. “Around 2,350 of us were arrested during our road block protest in Chennimalai in 2013, and hundreds of us were recently booked when we stopped the construction at Aayaparapu and Thalavumalai,” he said, adding that the protests are people-led and people-funded.On April 24, Ravi organised a conference in Perundurai, which involved 13 farmers’ associations and assembled 25,000 people, including women and children, in the forefront. The conference passed a resolution against this proposed concrete lining of the Lower Bhavani Project.Green Tribunal supportThe presidents of 10 panchayats in Erode and Tirupur filed a case on 24 May this year in the National Green Tribunal against this move. “Thirty village panchayats passed resolutions and sent them to authorities, who are now ignoring them,” said Mahasamy, one of the petitioners and president of Kandikattu Valasu panchayat. “If not stopped now, there’s a chance this project could be extended to branch canals.”Advocate Anandamoorthy, who holds an anti-concretisation stance, shared: “According to a 2006 notification of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and its subsequent amendment in 2018, the modernisation of existing irrigation canals or the formation of new ones in irrigation areas exceeding 50,000 hectares requires an environmental clearance from the ministry. However, this project has more than 83,000 hectares of ayacut area, and the government order passed for the proposed project was illegal.”In his petition, Anandamoorthy, who is representing the panchayat presidents, also quoted Section 48A of the Constitution, the directive principle which says: “The state shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country”. He also emphasised Article 51A(g), which proclaims it to be the fundamental duty of every citizen of India “to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures”.As the first step to success, the NGT on May 30 deemed the felling of trees for the project illegal in the absence of environmental clearance and permission from authorities. The tribunal also imposed an injunction against the Tamil Nadu government for proceeding with the project, making both the state and environment ministry answerable. Anandamoorthy, along with the panchayat presidents and the public, is looking forward to the next hearing on July 22.Every year, the canal receives water on August 15. For now, the movement can rest assured that the project cannot proceed at least till next year.Edited by Shraddha Chowdhury

Villagers in western Tamil Nadu dislodge polluting charcoal mills after decade-long fight to save groundwater

The charcoal industries in Kangeyam, which burnt and processed coconut waste in huge, open pits, were forced to stop their operation following dozens of protests by villagers and a definitive order by the National Green TribunalTirupur, Tamil Nadu: Kumar is a trader who buys coconuts from farms, dries them and sells copras (dried coconut kernels) to the hundreds of coconut oil mills that operate in the Kangeyam belt. This taluk in Tirupur district is known for its lush coconut farms and coconut-based industries, including those processing the nearly 500 tonnes of coconut shells which are generated as waste each month in the region, the 58-year-old said. "Now, there's an emerging market for coconut shell powder abroad and we are also exporting it,” Kumar said. At the turn of the millennium, however, the local market was dominated by charcoal mills. Earlier paper factories and cement factories used to buy coconut shells to be used as firewood but they couldn’t absorb the growing mountain of waste generated by the ramp-up in coconut production. When the charcoal mills started operating here on a full scale in the 2000s, little did the villagers know that their groundwater would soon start smelling of smoke, turn dark, contaminated with ash and become undrinkable. But their decade-long battle shut down all the charcoal mills in the belt, stopped pollution to their groundwater, and saved their cattle and agriculture.When the charcoal mills began functioning as a cottage industry in the region in the 1990s, Karthikeyan, the organiser of the protests, did not think that within a few years it would grow from burning roughly 2 tonnes of coconut shells per week in a few ‘pot pits’ (a small pot buried underground to burn the shells) to whopping 10 tonnes every day in each of these massive pits. The 45-year-old said that the pits, shaped like wells, are open and usually up to 7 feet wide and run 25 feet deep. Before and after: The charcoal mills, that used to burn and flush over 10 tonnes of coconut shells in each of these pits, now lie defunct, undone by massive public protests supported by administrative and judicial action (Photos: Gowthami Subramaniam)Impact on water quality and level“Once the shells were burnt, a huge amount of water was flushed into the pit. The charcoal was sold for activated carbon, and the remaining water and ash permeated the soil into the groundwater," Karthikeyan told 101Reporters. "If the burnt shells were naturally allowed to cool, the process wouldn't require much water. But to guarantee profits, often as high as 10 times the cost, huge amounts of water were splashed for faster results.”The excessive smoke from the charcoal mills was causing respiratory problems and eye irritation among residents in the area, recalled Balasubramani (60), treasurer of the protest groups. When their drinking water was contaminated, even the cattle refused to consume water from the borewells. This eventually became a huge financial burden for farmers who had to spend between Rs 1 lakh and Rs 2 lakh to purchase water from tankers for their cattle, he said. Already in 2005, people had started petitioning for the closure of the charcoal mills. Karthikeyan said that by 2008, in Veeranampalayam alone (a panchayat with a population of around 3,500), there were seven units with a maximum of 22 pits per unit. As there were no restrictions in place, each pit would burn about 10 tonnes per day and use 12 kilolitres of water per pit to douse the fire. When their groundwater turned blackish red and started tasting of smoke in late 2012, people from 22 villages around the mills staged various protests demanding their shutdown. They formed a union for the welfare of all those who were affected by charcoal mills.United in protestP Thangavelu from Veeranampalayam panchayat, who headed the protests recalled, “We had attended public grievance redressal meets every Monday to meet the collector. Every time, we were promised that action would be taken, but nothing was happening in reality.”The villagers then passed a Gram Sabha Resolution on August 15, 2012, demanding the closure of these units. The resolution said the mills should not procure any additional coconut shells, and that their operations would have to come to halt within 45 days. Veeranampalayam panchayat president Gandhimathi wrote to all the units demanding that they shut down permanently, which the mill owners countered. The matter then went to the Madras High Court, with five people adversely affected by the mills approaching the court as plaintiffs against the mill owners. People power: Following a gram sabha resolution to shut down charcoal mills that were using environmentally harmful techniques, the protests spilled over into the streets, reaching the Madras High Court, TNPCB and eventually the NGT. The Tribunal ultimately upheld the panchayat's rights to grant licences to industries, keeping in mind the health of the residents (Photos sourced by Gowthami Subramaniam)Further protests and roadblocks by over 2,000 villagers drew the attention of the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB), which shut down all the charcoal mills in the panchayat after examining the polluted groundwater. They have been closed ever since, although the mill owners continued the legal battle and sought police protection to run the units.After the high court denied their request, the pollution control board framed guidelines for the operation of the units. In its report submitted on November 27, it suggested the ban of all the mills' below-ground-level operations and having them shifted to above ground-level units with elevated tanks. The mill owners refused to accept the order, and the case was forwarded to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) by the end 2012.The process, however, was far from smooth, with politicians supporting the wealthy mill owners and the police booking the protesters on several counts, said Karthikeyan.Balasubramani added, “We spent between Rs 15 lakh and Rs 20 lakh to get anticipatory bail for 15 of us during the protests. We had to carry on with our protest, ignoring the threats by the police.”Green tribunal ensures justiceThe joint committee constituted by the NGT on February 29, 2020, declared that to continue natural restoration, the industries wouldn't be allowed to operate with the existing underground pit technology and were liable to pay environmental compensation of Rs 20,15,800 "for causing damage to the agricultural land"All the five plaintiffs received roughly Rs 1,00,000 as part of the compensation, and Rs 6,00,000 was allotted to the construction of a drinking water tank for Veeranampalayam Panchayat. The report also upheld the authority of the panchayat in deciding whom to grant licences, keeping in mind the health of the villagers.A decade after the mills were shut, groundwater still hasn't recovered, residents say. Some of the money that the mills were ordered to pay as compensation has been used to construct drinking water tanks (Photos sourced by Gowthami Subramaniam)According to current panchayat resident Umanayagi, the underground water has still not returned to its natural potability, and the panchayat has not been permitting charcoal mills using overground technology to operate here either. With the compensation of Rs 6 lakhs received via the compensation ordered by the NGT, a drinking water tank with pipelines to neighbouring farms is being constructed at Pallavaralayampalayam in Veeranampalayam panchayat. After more than a decade of suffering, the people of Kangayam taluk earned their right to pollution-free lives. The NGT report forbidding the operation of these units using outdated technology inspired people from Dindigul, Palladam and Udumalpet against illegal coal mining, as well, says Karthikeyan. The villages stood up for themselves and not only ensured their right to clean water but also reinforced the rights of panchayats in upholding the interests of the people. Edited by Rashmi Guha Ray All photos clicked or sourced by Gowthami SubramaniamThis article is a part of a 101Reporters' series on The Promise Of Commons. In this series, we will explore how judicious management of shared public resources can help the ecosystem as well as the communities inhabiting it.

.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Write For 101Reporters

Follow Us On

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All News