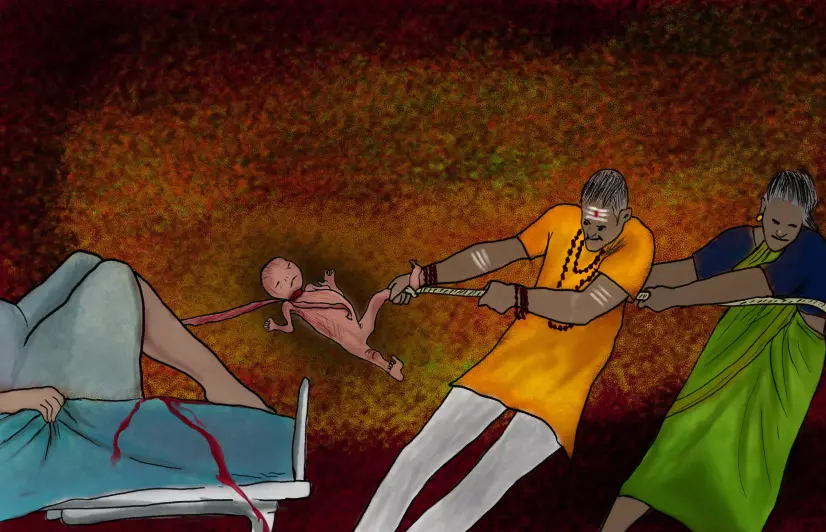

Tamil mothers forced to risk health of new babies to avoid 'inauspicious months'

Tamil mothers forced to risk health of new babies to avoid 'inauspicious months'

Families push for induced labour or elective C-section to avoid ‘inauspicious’ Tamil months of aadi and chithirai, but seldom understand the risk that such acts pose to the lives of both mother and child

Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: When Valli* came home after a complicated delivery in 2016, her family blamed her baby boy for “terrifying them during his birth”.

“Nobody realised the trauma he went through because they forced his delivery!” wept Valli, whose nurse-mother had coerced the gynaecologist to artificially induce labour at 36 weeks because she did not want her grandchild to be born in an ‘inauspicious’ month.

Valli had conceived after battling with polycystic ovary syndrome for two years, but when she shared the good news, her mother was quite cryptic. “That means the baby will come in chithirai month!” she remarked.

Chithirai (March-April) heralds the Tamil New Year, but many families believe that a birth in that month would essentially mean difficulties in future life. And thus began Valli’s trauma.

“My mother kept asking me if I wanted to give a troubled life to my child. I knew that was absurd, but I was not emotionally fit to think critically. I was afraid people would blame my baby if anything went wrong in future. That fact really affected me.”

Since her mother had earlier worked as a nurse in the same hospital where Valli was consulting, she convinced the doctor for a delivery before chithirai, though the due date was May 15. “The baby did not descend easily as labour was induced artificially. My cervix failed to efface and became hard as a rim. The baby also developed a scalp swelling (Caput succedaneum) due to repeated forced contractions,” said Valli, who had been a nurse in the same hospital.

As she was averse to the idea of a Caesarean delivery (C-section), the gynaecologist supported her in a vaginal birth by manually dilating the cervix from six cm to 10 cm. That led to a foetal distress and a sudden heart rate drop between 40 to 60 bpm against the normal 140 to 160 bpm.

“Separated just by a screen was another woman delivering her dead foetus. I could hear everything happening there. That doctor even shouted at my nurses to shift me for an emergency C-section as my baby had Bradycardia (slow heart rate) and no pulse… By that time, my gynaecologist had gone to attend to another woman who opted for a C-section due to a medical condition similar to mine,” Valli recounted everything that went wrong around her.

“I had flashbacks of my previous miscarriage, failed fertility treatments, and the long wait for conception. What if I lose this baby too? I kept talking to the baby expressing my love,” said Valli.

It was nothing short of a miracle to her when the doctor came back and extracted her baby vaginally using forceps. “The baby had mild breathing issues and was kept in the neonatal intensive care unit for the first few hours,” she said.

Months of ‘peril’

Risky births are becoming common in the days leading up to the months of chithirai and aadi (June-July). Nalini* of Erode was to give birth during aadi in 2018, but her family cited examples of aadi-born people who did not do well in life. As if to add fuel to fire, an astrologer had told the family that she would deliver a baby boy, but the birth in aadi would be most inauspicious.

“I did not worry much until my mother asked the gynaecologist if I can be put through an elective C-section 20 days prior to the due date. I was taken aback. I felt so bad that nobody even required my consent,” Nalini told 101Reporters. Luckily, for Nalini, her doctor did not yield, but patiently explained to my mother about foetal development and the need to go full-term.” Despite that, Nalini underwent an emergency C-section, which she believed was the result of the negative environment that the people around her had created.

While the State government does not share data on monthly delivery caseload, the maternal healthcare infrastructure remains practically overburdened during chithirai and aadi. It was during the 38th-week check-up of Hasini* that her mother-in-law pleaded to the doctor to prepone her delivery to avoid aadi. “The doctor did not heed due to slot unavailability. She said I will have to wait for another week for C-section.”

“But my mother-in-law persisted and there I was, waiting till 9 pm in the hall to get a room for delivery the next morning. Meanwhile, my family tried to convince me to opt for an induced birth. Apparently, they were more worried about the possible delays in C-section procedure as the hospital had a high caseload preceding aadi. But I remained adamant… Despite a sleepless night, my baby was born healthy. But we remained separated for four hours straight. I was not moved to the room even two hours after my anaesthesia wore off as the hospital staff were too busy.”

An Erode-based anganwadi worker who has been monitoring and assisting pregnant women for over two decades shared on the condition of anonymity that around 20% of expectant mothers in her area went for elective C-sections to avoid aadi and chithirai. "No one understands the risks!"

Busting the myths, medically

In her over 30 years of medical practice in Coimbatore, Dr Saraswathi has lost patients for not agreeing to preterm deliveries. “I may lose my income, but not my sleep,” said the obstetrician-gynaecologist whom Nalini had consulted.

She noted that families often compromise a woman’s right to her body by misusing her state of emotional vulnerability, driven by hormonal imbalance. “Uterus prepares for labour from the 37th week. So why should we interfere in this natural process? Moreover, C-section is a live-saving procedure that should only be performed for the right reasons.”

Kanimozhi Senthamarai Kannan, a lactation consultant in Coimbatore, told 101Reporters that induced birth or elective C-section can lead to severe lactation issues. “After the placenta is delivered, the body receives a cue that the baby is born and it starts secreting milk. In the case of scheduled birthing, the body will take time to realise that the birthing is over, which affects immediate breastfeeding.”

“Women going through scheduled births face breastfeeding issues and have to depend on baby formulas. Most C-section borns also do not get immediate skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding in the first hour of birthing due to NICU admissions. Both lead to breastfeeding obstacles such as improper latching, sucking, breast refusal and respiratory distress, besides leaving a difficult blotch for mothers to cope with.”

Dr Karthick Annamalai, a paediatrician and neonatologist in Coimbatore, told 101Reporters that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists defined 39 to 40 weeks as full-term, 37-38 weeks as early-term, and 34-36 weeks as a late preterm. “During the scan in 35-36 weeks, some babies are found to have gained weight. Families misunderstand weight for maturity and request for C-section. But they do not understand the importance of the baby's last month in the womb.”

He said a baby born at 28 weeks as a result of spontaneous preterm labour would be healthier than an elective C-section at 36 weeks because naturally released stress hormones result in higher cortisol levels, thereby maturing the lungs and brain of a foetus. “Baby receives oxygen from the placenta inside the womb. The lungs start functioning only after the baby cries after parturition. This transition to extrauterine life is difficult, especially when babies are forced. In cases when the lungs are still wet, it calls for an NICU admission. Complete liver development is also not promised in preterm babies, putting them at a grave risk of jaundice.”

“For a healthy brain and emotional well-being, babies require a naturally safe environment like a mother’s womb or lap. Studies have suggested that preterm babies may have lower IQ levels.”

He further threw light on how the medical fraternity avoided legal consequences by not indicating the procedure as ‘elective’. “They mask it with some health indicators.”

“Deliveries in the 34th week are the most common during aadi or chithirai, especially if that is twin or IVF pregnancies. Since both these cases are riskier, and IVF treatments cost a fortune, families are more insecure of births in aadi or chithirai,” said Dr Annamalai. Revealing that even margazhi (December-January) has become inauspicious of late, he said he did come across several such cases last month.

Dr Pradeep V Krishnakumar, City Health Office, Coimbatore, admitted that familial or social pressure was behind elective C-sections. "Unlike private hospitals, such incidents are rare in government hospitals or Primary Health Centres. We always strive to increase the number of normal deliveries in government hospitals."

Summing up, Dr Annamalai said, “the good day for a birth has to be whenever the baby decides to meet the world.”

*Names changed to protect the identities of the individuals

Cover Illustration by Prajwal M

Edited by Khwaish Gupta

Would you like to Support us

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All NewsAbout the Reporter

Write For 101Reporters

Would you like to Support us

Follow Us On