Complainants in petty theft cases bear the brunt of police interrogation

They are treated like accused when they report theft of valuables at police stations, so they mostly prefer not to pursue the complaint furtherKhandwa, Madhya Pradesh: The day he was robbed, Sheikh Rafiq (48) of Badhiyatula in Khandwa district could not sleep. The next nine nights were no different as he was distressed by the way the police kept harassing him. They behaved as if he were the accused and not the complainant, his family said. By the tenth day, he died by suicide. “Within those 10 days, the police contacted almost every relative of ours in the district, got their details, including about their work, obtained their bank account details and got information from them about my father. The day before my father committed suicide, the town inspector contacted him and asked him to bring my mother to the police station,” said Rafiq’s son, Sheikh Wasim.Elder and younger sons of Sheikh Rafiq of Badhiyatula in Khandwa district (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)“Considering the police’s insulting behaviour, my father did not wish to take my mother there, but he also knew the consequences of avoiding the police. Upset over this, he left home at midnight, but we were cautious enough not to let him fall off our radar. We brought him back home, but he left the house again around 4 am, when everyone was fast asleep, and jumped in front of a train,” Wasim detailed.Wasim accused the town inspector of harassing Rafiq when he was called to give his statement. The money totalling Rs 81,000 was snatched away when Rafiq was returning home after selling the produce in the market. “My father was carrying his own money, and he did not even have to give an account of it to anyone. How could he lodge a false complaint?” Wasim said, his younger brother, Sheikh Hashim, narrated the same story.“I was with him when the town inspector contacted him. His wife was being called to the police station. No woman from this family had ever gone to the police station. He was very worried about this; he knew that the police would treat his wife in the same way as they treated him,” Naeem Khan, the brother-in-law of Rafiq, told 101Reporters.The police registered a First Information Report (FIR), but continued to harass the complainant as they considered this case to be fake. However, Khandwa District Superintendent of Police Manoj Rai differed on this. “If the police will not interrogate, how will the investigation progress? Police investigate all the points in every case. Whatever cases come to the police, they take them seriously. Only then does the public's trust in us get strengthened,” he told 101Reporters.Police attitudes However, a study on non-registration of crimes by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in 2017 indicates that unruly behaviour by the police deters about three-fourths of the Indian population from reporting complaints. And, of course, not all complaints result in FIRs. The same study posited that less than 10 per cent of crimes in society are actually getting registered. It also quotes a 2017 Crime Victimisation Survey conducted in major Indian cities to indicate that only about seven per cent of victims of theft lodged an FIR.“The reason police stations hesitate to register theft cases is that in most such cases, the thieves are not caught, and these cases remain pending. Because of this, the officers posted there stay under constant scrutiny from higher authorities, especially during crime meetings when police functioning gets reviewed,” said Pradeep Singh Ranawat, Retired City Police Superintendent from Jaora. “It becomes necessary to justify how much property was stolen and how much of it has been recovered. To avoid these situations, police personnel often neglect or hesitate to register theft cases.”“Once an FIR is registered through any means, the police cannot cancel it. Such cases must be presented in court. Therefore, the primary aim of police officials is that pending cases should not appear, and the number of registered cases should appear lower compared to the previous year,” he said. In the State of Policing India report 2019, focusing on Police Adequacy and Working Conditions, a survey of nearly 12,000 police personnel across the country found that 54 per cent believe that an increase in the number of FIRs registered indicates an increase in crime in the area, as opposed to an increase in registration of complaints by the police. In the chapter ‘People-friendly Police or Police-fearing People?’, the report notes that the common complaint in India is that police refuse to lodge FIRs, likely due to the mistaken notion that high crime rates reflect poorly on police performance. On top of this, 37 per cent of personnel feel that for minor offences, a small punishment should be handed out by the police rather than a legal trial.Scams, goats and other missing FIRsUnsurprisingly, we see these attitudes playing out over and over among victims and their interactions with the police when it comes to petty crimes. Living in Bhatalpura village on the border of Khandwa and Khargone districts, Nanibai Bhalrai (66) works as a labourer in the fields of both districts. She takes up agricultural work for six months and grazes goats the rest of the year.Nanibai Bhalrai, her complaint could not be lodged due to jurisdictional issues (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Three months ago, when she woke up in the morning, five of her goats, worth Rs 80,000, tied in the courtyard of her house were missing. Due to jurisdictional issues, Bhalrai kept running between Deshgaon and Bhikangaon police stations. Yet, her complaint could not be lodged. Bhalrai desperately searched for the goats in the meantime and, after 15 days, managed to find them grazing in a field near Devjhiri, 10 km from Bhatalpura. Though she tried hard to find out who was grazing them, she did not succeed. But Bhalrai is happy that at least her goats are back. In another case, Khandwa-based readymade garment businessman Anup Kumar Gurbani (68) was duped during his morning walk on May 19, but the police found it convenient to put him under the scanner.On May 19, Gurbani found himself the victim of an elaborate scam, which claimed his gold ring, and he reached the nearby Padam Nagar Police Station to lodge a complaint. However, the police did not accept his complaint and asked him to come the next day. The next day, when he reached the police station again, the assistant sub-inspector started interrogating him. His complaint of fraud could not be lodged that day as well. After the incident, Gurbani stopped going for morning walks alone. Tired of the police's questions, Gurbani also gave up the hope of getting back his gold ring.For those bypassing humans, the process isn’t smooth either. When Amin Ahmed Shaikh (43) of Khandwa registered an online FIR for a theft that happened on February 27, the police put pressure on him to withdraw the case. Shaikh told 101Reporters that he owned a farm at Badgaon Bhila in Nagchoon panchayat. To secure the place, he brought fencing material to the farm. However, a lot of goods were stolen from there. Upon investigation, it was found that 10 fibre chairs and 60 iron angles of 5 ft length, worth approximately Rs 15,000 to 18,000, had been stolen.When he filed an online FIR, the police were not keen on recording it in the manual register. Instead, the town inspector put pressure on him to withdraw the complaint. He withdrew the complaint, but the thieves are still at large. The problem of ‘missing FIRs’ is well-acknowledged. A parliamentary panel in 2017 questioned the basis of government claims that around 78% (approximately 12,000) of police stations in the country are registering 100% FIRs. At that time, the committee strongly recommended that the government consider making refusal of registration of FIR by police personnel a criminal offence and that action be taken against such erring police personnel.Ranawat remembers that there were provisions under the IPC to record thefts of less than Rs 1000. They were registered with a clear mention that the FIR was merely for record and that no detailed investigation would be carried out. The new laws are clearer, stressing on community service and swift disposal of such cases. Notably, Section 283(1) of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita grants Chief Judicial Magistrates and first-class Magistrates the power to conduct summary trials for certain offenses, such as petty theft where the value of the property does not exceed Rs 20,000. And Section 303 (2) of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita states that if the stolen property is worth less than Rs 5,000 and it is a first time conviction for the person, he/she may be punished with community service if the said property or its value is returned. This story was produced for and originally published as part of the Crime and Punishment project in collaboration with Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

PESA empowers tribal villages in Madhya Pradesh, but roadblocks remain

From illegal mining to local disputes, PESA committees are asserting their rights, sometimes clashing with contractors and administration in the process.Khandwa: Two and a half years after its implementation in Madhya Pradesh, the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act of 1996 (PESA Act) is empowering tribal communities in unexpected ways. Once focused on local disputes and regulating liquor sales, PESA Committees are now directly confronting bigger threats, including the mining mafia. But asserting these newfound rights often puts them on a collision course with local administration.For example in Madhya Pradesh’s Khandwa district, a PESA committee is protesting against illegal murram mining, but has received little support from the administration. In Dhawadi village of Khalwa tehsil—just 70km from the district headquarters—a road construction company, LEA Associates South Asia Private Limited, has been openly extracting murram from about 12 acres of grazing land. This land, under the Revenue Department, falls within the local panchayat’s jurisdiction, according to Barelal Karochi (55), Chairman of the Dhawadi PESA Committee.Barelal Karochi, Chairman of the Dhawadi PESA Committee (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)“On April 27, the company started mining with over 20 dumpers and five dozer machines,” Karochi told 101Reporters. “Villagers quickly mobilised to stop the operation but were informed by the contractors that they had permission for the mining from the government.”In response, an emergency Gram Sabha was held the next day where villagers decided that no mining would be permitted. The PESA Committee informed the company officials, but their concerns were ignored, Karochi added.On April 29, PESA Committee members went to the mining site and demanded that work cease. It temporarily stopped, but the Tehsildar arrived at the company’s request and told villagers that the Panchayat had already granted permission, warning that anyone who interfered would face action.The PESA committee then called for a meeting with the Panchayat and administration, but neither officials nor company employees attended.Ashutosh Singla, the PESA District Coordinator, said that the Gram Panchayat had indeed given clearance to the company for the mining, which has continued since April 28.Gram Sabha was held where villagers decided that no mining would be permitted (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)BackgroundAt the PESA’s core are the tribal-dominated areas in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, all designated as Scheduled Areas under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution.In Madhya Pradesh, PESA came into force in November 2022. Under the PESA, the powers of a village council are absolute. Its approval is necessary for land acquisition and other development plans. The tribal communities own and manage natural resources (water, land and forest resources, including minor produce) in the area, and the council monitors and implements laws in this regard. The Gram Sabha has a say in the grant of prospecting licences or mining leases for minor minerals and in the grant of concessions for the exploitation of minor minerals by auction in the Scheduled Areas.A Gram Sabha has the mandate to uphold the unique tribal cultural identity. Hence, they also have the power to scuttle any development programme that affects their vibrant tradition. In districts where the PESA Act is implemented, the Gram Sabha automatically functions as the PESA committee. To support these committees, mobilisers are appointed at the Panchayat level, while coordinators are designated at both the district and Janpad (block) levels to provide broader support.The village council’s influence in the social sphere gives it the power to select beneficiaries of government schemes, act against moneylenders, protect the rights of workers, monitor and grant permission for migration/arrival of labourers, and manage village markets.Gram Sabha has the mandate to uphold the unique tribal cultural identity (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)UnaidedPESA District Coordinator Singla, whose role is to educate PESA Committees about their rights and responsibilities, said a significant challenge these bodies face in the district is lack of administrative support. “For any work involving mineral resources here, they [the PESA Committees] are not consulted.” This implies the administration isn’t ensuring Gram Sabha consent—central to PESA—is sought before decisions on village resources are made. This lack of adherence to the Act’s provisions prevents PESA Committees from operating effectively.Gram Panchayat of Dhawadi (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Singla cited the Dhawadi Panchayat incident as an example. In Dhawadi, the Panchayat issued a No Objection Certificate (NOC) for mining without first obtaining permission from the PESA Committee. When the committee attempted to stop the mining, the Tehsildar used the Panchayat’s NOC to pressure them.According to Singla, there are 155 Panchayats in the district, but without consistent government support, they cannot make any significant impact. There’s a lack of coordination between the Panchayat and the PESA Committee, he added. To understand why the Panchayat issued an NOC for the mining project, 101Reporters tried to contact Sarpanch Monu Ramfal Karochi in Dhawadi but she was unreachable. Efforts to contact Panchayat Secretary Asif Khan were also in vain. He picked up his phone once and said that he was in a meeting and would call back. He is yet to respond to subsequent calls.Panchayat Mate Rakesh Ivne (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)BypassedPanchayat Mate Rakesh Ivne said that the contractors’ claims that the Panchayat provided the permission is not without doubts. “The contractor’s people are showing permission from the Panchayat,” he said, “but the Panchayat cannot grant permission without the Gram Sabha’s approval”. The contractors are either misrepresenting the Panchayat’s authority or operating with an approval that bypasses the mandatory Gram Sabha consent, he added.For Karochi, the situation in Dhawadi village is an affront to PESA’s spirit. “The Gram Sabha has the right over the property of the village and it will decide how it should be used,” he said.According to the information provided by Tehsildar Rajesh Kochle to Additional Collector KR Barole the mining was approved based on a “no objection” received by the panchayat. Kochle noted that only some members of the PESA Committee are against the mining. Karochi, however, denied this claim saying that the “entire Gram Sabha” wants the company to not do any kind of mining there. Sunita Kavade living in Dhawadi (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Sunita Kavade, a resident of Dhawadi, explained that the villagers are against the mining because of its severe environmental effects. Currently, the company is mining on five acres, but Kavade is expecting this area to expand. “The animals of the village go there to graze in summer. They are digging in 12 acres of land. Where will the cattle graze now?”Small victoriesBeyond the battles against illegal mining, PESA committees are quietly transforming life in these tribal villages, securing local resources and resolving long-standing disputes.Rohit Gautam, a PESA Gram Sabha Mobiliser appointed by the Tribal Development Department, explained how the Gram Sabha is steadily growing in strength, ensuring village resources and revenue stay within the community. He cited an example from Deolikala village, where the Gram Sabha last year halted the auction of a village pond, preventing its exploitation.The PESA Committee has also set up a system to protect migrant workers. Every year, many from Dhawadi migrate for work, often exploited by contractors. For this, the committee implemented a mandatory contract system. Contractors must now deposit a fixed amount and a list of migrating villagers with the committee, detailing names, wages and work. A neighboring Panchayat, Chakara, has adopted a similar system. For instance, a farmer from Karnataka deposited Rs 5,000 with the Dhawadi PESA Committee as part of a contract.Karochi said, “Earlier, there were only verbal contracts. Contractors would give advance money and take labourers, often failing to pay the full amount.” Now, the committee collects a security deposit which is returned if the labourer is treated fairly. “Labourers have always been exploited, but after PESA Panchayats formed, we’ve started monitoring this closely,” he added.Shift in local governanceTwo and a half years ago, 101Reporters covered the election of the PESA Committee in Devlikala Gram Panchayat, Khandwa district, Then, many elected members had little understanding of the Act. Only the Panchayat Secretary seemed well-versed. Committees gradually gained awareness of their rights, enabling them to make significant decisions. In Dhawadi Panchayat, after new elections following the passing of its first PESA committee president, Ramsharan Maskole, inactive members were removed, leading to quicker and more decisive actions.The PESA Committee is now playing a crucial role in village governance. In Dhawadi, for instance, PESA Mobiliser Sulochana Karochi said no case has reached the police station since the committee became active in January 2023, all village matters are now resolved internally.PESA Mobiliser Sulochana Karochi (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)She cited a long-standing land dispute between an uncle and nephew that nearly turned violent. “The dispute was regarding the path to their respective farms,” Sulochana said. The PESA Committee intervened, resolving it through mutual agreement. “Both parties agreed that they will not stop anyone from coming and going.”The hearing process is transparent and community-led. “The Gram Sabha is announced by beating drums in the village,” Sulochana explained. “There’s a group discussion, and before a decision, voting is done by raising hands. The chairman takes the decision unanimously, and everyone accepts it.” Cover Photo - PESA Committee is now playing a crucial role in village governance (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

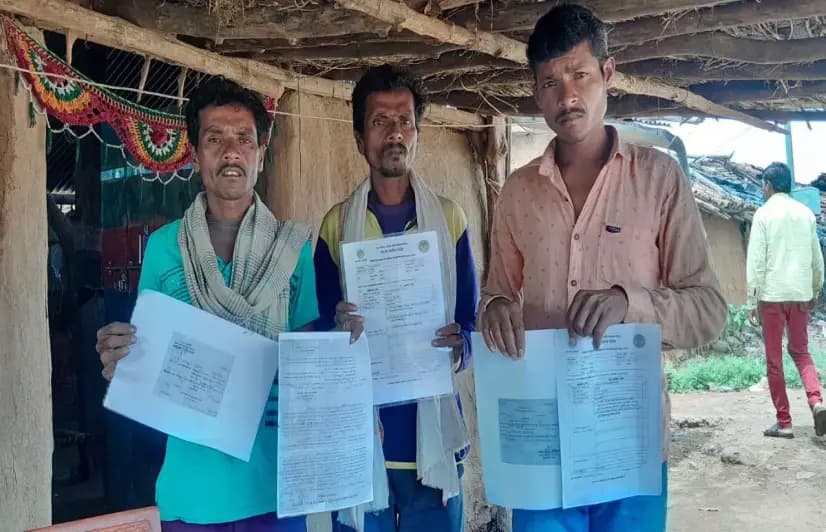

Punishment for protest is jila badar

Tribals in Burhanpur who have been fighting to save their forests and access land documents caught unawares by false cases, direction to leave district boundaries Burhanpur, Madhy Pradesh: Sitting on a charpoy near his agricultural land, Dilip Sisodia (42) of Chainpura shows an 85-page notice served by the district administration proposing his removal (jila badar) from his native Burhanpur district under Section 5 of the Madhya Pradesh Rajya Suraksha Adhiniyam, 1990. Besides Burhanpur, the notice informs him to stay out of Khandwa, Khargone, Barwani and Harda districts.According to the Act, a person can be removed outside if there are reasonable grounds to believe that the individual is engaged or is about to be engaged in the commission of an offence, or in the abetment of an offence. It is commonly used against habitual offenders and miscreants, with the district magistrate possessing the power to transfer such a person out of the district at his/her discretion. Using the powers under Section 5 of the State Security Act, the district superintendent of police (SP) makes a proposal for removal of a person and sends it to the district Collector/magistrate, who is the final authority in matters related to jila badar. After approval, the Collector will pass the proposal to the divisional commissioner. Hearings of the person to be removed are held at the Collector's court. Here the person in question gets a chance to refute the allegations raised against him/her, although this hearing is just a matter of formality. Following the Collector’s decision, the person in question should leave the area or district limits, whichever applies, within 48 hours. The SP should be informed about the person’s place of stay during jila badar. If any case is pending against the accused, he is given conditional permission to come to the district for court appearances. That apart, if the accused is seen in the district even a day before the deadline, he/she can be jailed for three months to two years with a heavy fine. The fine may differ in each case.Sitting on a charpoy near his agricultural land, Dilip Sisodia (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)In Sisodia’s case, the notice mentioned the 10 cases registered against him. However, he claims that all these cases have false allegations. “Under Section 307 of the Indian Penal Code, a case was registered against me for attacking forest department staff at Jamun Nala Navra on October 10, 2022, although I was not here at that time. The then ranger had also said in his statement that he does not know me and that the case was registered on someone else's request,” Sisodia claimed. Sisodia was given time on May 9 and 15 to present his views at the Collector's court in Burhanpur, located 30 km from his village Chainpura. The final hearing was held on May 27.“My crime is that I have applied for a land lease," Sisodia asserted. While many old settlers have received land leases under the previous BJP government, more tribals have been taking to the protest path last year to put pressure on the government to provide leases in the election year.Tumultuous daysClashes between tribals protesting for their rights and the administration are nothing new to Burhanpur. For two days in April last year, the old tribal settlers under the aegis of Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangathan (JADS) launched an indefinite sit-in protest before the Burhanpur Collectorate, alleging that the forest department has been allowing newly-migrated tribals to clear forests and settle there in exchange of the cut timber. The protest ended two days later, on April 7, when some of the alleged forest cutters were arrested. However, the same night, a group of new settlers attacked Nepanagar police station and freed the arrested men, further escalating the situation.The JADS alleged that the administration has weaponised the protest to order its participants to leave the district boundaries. First, JADS leader Madhuri Ben was banned from entering the district, then other tribals were shown the door one by one.Madhuri Ben (55) told 101Reporters that JADS have been protesting the uncontrolled harvesting happening in Siwal, Bakdi, Mandwa and Badnapur in Nepanagar tehsil of Burhanpur district for a long time. “The forest department failed in catching the new settlers, so they started harassing those who have been living here for generations. As the pace of harvesting increased, our movement also intensified. From January last year onwards, we moved beyond complaints to protest,” Ben said.Madhuri Ben talking to 101Reporters (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)After the police station incident, the forest department transferred the divisional forest officer (DFO). Within a week of the new DFO taking charge, a joint press conference was organised with the administration on May 2 last year. In this, a preliminary offence report with 21 charges related to involvement in forest crimes were filed against Ben. “It should be noted that on April 10, we went to Bhopal and made a written complaint to the Director General of Police seeking action against Burhanpur SP. Nine days later, on April 19, a case was registered against me and my colleague Nitin Varghese." The case was registered under Sections 294 and 323 of IPC and Section 3(1)(d) of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, among others."Exactly a month later, on May 19, the district magistrate's jila badar notice was issued in my name. I applied for reconsideration of the matter before the Indore Commissioner, but it was declined after four months, upholding the Collector's decision. Now preparations are being made to take the issue to Indore High Court,” she said. According to Nitin Varghese, the punishment meted out by the district magistrate acted like ostracisation. “You can neither meet your family nor contribute towards family expenses. When the earning member of the family is thrown out of the district, it becomes difficult to manage the expenses. It is difficult to go to a new place and find work also. A house should be rented out at the place where he would live and he has to depend on the family to meet his expenses.”Subsequently, the district administration allegedly targeted Antram Awase (34), a tribal leader and JADS worker from Siwal, by serving a removal notice. “Whenever we asked for help, we faced harassment. Sometimes we were shot at, sometimes we were sent to jail, and now we have even been ordered out of our homes and families by citing false cases against us,” said Awase, who is serving a sentence in Khandwa jail after the mass movement in Burhanpur last year.Awase said cases were registered against him along with hundreds of others from Dwali, Siwal and Chainpura. “I was in jail for 17 days. The rest of the people are also out on bail now.” According to Awase, the forest department has always been after them. Citing a July 9, 2019, incident, he said the forest staff reached their fields with hundreds of vehicles and nine JCBs and started digging potholes in the fields.(Above)Antram Awase talking about the forest department (below) Chainpura in the fields (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters) “When we protested, they fired on us. In this, villagers Gokhar Singh Gathia, Rakesh Rama and another person suffered shrapnel injuries. The department's action was completely against the rules. Under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, people with lease claims cannot be evicted, whereas Section 4 and Sub-section 5 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, were applicable at these places. During the COVID-19 period, our forest rights claims were rejected without investigation and without gram sabha approval [gram sabhas operating in forest villages are under the forest department's control]. The claims can be cancelled only after verification and inspection. We have once again applied for this.”As many cases as land claimants So far, about 10,000 tribals (these include residents who settled here after 1979 and before 2005) have applied for lease under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, in Burhanpur district. According to Sisodia, 129 families from Chainpura have made land claims. “The administration has selectively registered cases against these families. After last year's movement, the number of cases has increased. Even criminal cases have been registered against 100 members of these families,” he said. “Our elders have been living here since 1979. At present, claims are rejected stating that the place was not occupied in 2005. However, we have records of 1979, 2000 and 2001 with us in the form of notices from the forest department. If we came to live here in 2005, how did the forest department issue a notice in 1979 in the name of my family? In the latest notice that I received, it is clearly written that I am being arrested for protesting under the JADS banner. They are trying to crush the movement by imposing cases on us,” Sisodia detailed. Jila badar usually lasts from three months to one year. Sisodia said he could have come out on bail in a month or two and taken care of his farm work and family if he was sentenced to prison. “I am worried about my family. What will be their condition once I am thrown out of these five districts?” he said in despair. As of January 2025, Madhuri Ben's expulsion from the district has been completed, although she has filed a petition against it in the High Court, but no decision has been taken in this case till now. While Dilip Sisodia is still expelled from the district, the High Court gave its verdict in Antram Awase’s case, declaring the illegality of jila badar and imposing a fine of Rs 50,000 on the administration.This story was originally published as part of the Crime and Punishment project in collaboration with Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.Cover photo - Representative image/ AI-generated using Canva

_(3).webp&w=3840&q=75)

After cotton, pink bollworms devour wheat crop in Khandwa

As input costs increase and yield declines, farmers are trying their luck using pesticides over and above the stipulated quantitiesKhandwa, Madhya Pradesh: “I am a big farmer. What I used to get from 15 acres three years ago is what I get out of 30 acres today. We had never seen pink bollworm in wheat until then, but today, its infestation has reduced the wheat crop by half and increased cost of farming by two times,” says Harish Patel (70) from Bamjhar in Madhya Pradesh’s Khandwa district. “Earlier, 20 to 22 quintals of wheat could be produced from one acre without using any pesticide. Now, even after spraying chemicals, the yield has come down,” claims Jagannath Kanade (78) from Temikala. He got only six quintals of wheat from one acre this rabi season, which is only one third of the normal yield he used to receive. He says caterpillar infestation was less last year when compared to this year.Farmers (above)Jagannath Kanade and (below) Kamlesh Gurjar (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters) Ramesh Patel (45) of Bherukheda Chichgohan is sure that farming is no longer profitable. From three acres of land yielding 45 to 50 bags of wheat, he has not been able to get more than 30 bags in the last two years. “Wheat production has been continuously declining in those two years. This time, pesticides had to be sprayed multiple times to deal with pink bollworms. Farming has become more laborious than before,” he says.Data on irrigated area and productionIn comparison to 2021-22, an additional 29,308 hectares were irrigated in Khandwa district in 2023-24. While 2,887 kg wheat per hectare was produced in 2021-22, a decline of 87 kg in production was recorded in 2023-24, despite the increase in irrigated area.This medicine is used to trap pink bollworm (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)The pest was first seen in cotton years ago, before wheat and soybean began to fall prey. “To prevent pink bollworm infestation in cotton, we installed pheromone traps in our fields as per the advice from agricultural scientists. This experiment was successful to a great extent,” says Harish. However, farmers are not using pheromone traps in wheat, and are instead betting on pesticides because they are comparatively easier to use, though they are more expensive than other methods.Ramesh used the trap given by Bhagwant Rao Mandaloi College of Agriculture, Khandwa, to protect his cotton crop from the insect and succeeded largely. “About 45 farmers in my village used this trap and everyone got good results,” he says.Harish adds that they have made some gains from cotton, after suffering losses in wheat and gram. “Agriculture college gave us traps this time. In the next crop cycle, we will instal traps at our own expense.” Each pheromone trap costs between Rs 50 and 80. According to Dr Satish Parsai, entomologist, Bhagwantrao Mandloi College of Agriculture, the trap does not kill, but confuses and entraps the male insect. The trapped male is unable to come into contact with the female, hence their reproduction gets hampered.This is a simple equipment with the smell of a female insect applied on the lid of the funnel-shaped main part. This attracts the male pest. In this trap, a chemical mixture of Profenofos, Quinalphos, Flonicamid and Emamectin Benzoate are added to kill the male pest.“Trapped caterpillars are counted for three days and nights. Once around eight male caterpillars are found trapped, we ascertain the scientific treatment [pesticide] to be adopted,” says the scientist.Use of pheromone traps has two advantages Even before the pest attack is evident, farmers get to learn about the impending attack when the pest gets trapped. The second advantage is that the trap prevents reproduction of pests by segregating males. This helps in reducing the intensity of the outbreak, which also reduces the cost of pesticides to be applied by almost a half. In fields where pheromone traps are not installed, Rs 25,000 per acre has to be spent on pesticides. Where traps are installed, this expenditure will come down to less than Rs 10,000.Entomologist Dr Satish Parsai (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Conflicting opinionsScientists have advised farmers to do deep ploughing and leave the shallow land open for a few days so that the insects growing in it are destroyed. Along with the wheat crop, they have been told to plant other food grains, except in ridges and a few rows.However, to reduce the cost of farming, farmers try to avoid deep ploughing. They do not plant other crops in the field along with the main crop. The logic behind this is that different pesticides have to be used for different crops. Therefore, emphasis is on planting only one crop. Speaking to 101Reporters, Saurabh Gupta, Weather and Agricultural Scientist, Bhagwant Rao Mandaloi College of Agriculture, Khandwa, says pesticides are recommended only when necessary. Nevertheless, farmers go two steps ahead and add more medicines to the prescribed dosage. “Farmers have started to use medicines even before the fungus appears. Where five sprays of medicines are recommended, the shopkeeper recommends eight to 10 sprays and the farmer does 15 sprays. All these cause harm to land, humans and the environment. Chemicals are being added every 10 days for the 100-day crop. We recommend chemicals only if at least two to three caterpillars are found within a three by three ft area. But farmers start applying pesticide even after finding one caterpillar,” Gupta explains.This is how caterpillar catching traps are set (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Officials in denial modeWheat production in Madhya Pradesh has continuously declined in the last three years. Wheat production in the state has decreased from 371.98 lakh metric tonnes to 349.23 lakh metric tonnes in 2020. Replying to a question from MLA Sohanlal Valmik in the State Assembly on July 12 last year, Food Minister Bisahulal Singh said wheat production in the state was 371.98 lakh metric tonnes in 2019-2020, 356.69 lakh metric tonnes in 2020-21 and 349.23 lakh metric tonnes in 2021-22. This means there has been a decline of 22.75 lakh metric tonnes in wheat production in three years. However, the minister did not touch upon the reason for the decline in production.Questions were also raised during the same session regarding the presence of pink bollworm attack in wheat and the resultant decrease in production, but the minister did not acknowledge this.When asked why per hectare production of wheat declined in Khandwa despite the increase in area of irrigation, district agricultural welfare officials called it a normal process and refused to attribute the crop loss to pest attack. In fact, it has emerged that the government figures and farmers' claims are not matching.Agriculture Welfare Officer KC Waskle tells 101Reporters that irregular rains led to the present situation. “The adult insect lays eggs and the larvae emerge from it. It turns into pupae later. In the kharif season, when soybean and maize are planted, the pupae enters the soil. However, when it gets the desired environment like rain or humidity, insects emerge again,” Waskle says.Gupta, meanwhile, highlights the need for a weather advisory. “Today, changes occur in a jiffy. Absence of cold and rain, excessive heat, or clouds appearing do not call for an increase in the intensity of pesticide use. The right medicine has to be given at the right time. It should be administered at an interval of 21 days… The biggest problem in agriculture is irregular weather patterns,” he says.On soil health in Khandwa, he says investigations have revealed that acidity and alkalinity of the land here have been increasing. Friendly insects are also dying due to the use of pesticides. "The soil itself has a mechanism to stop these insects. It heals itself, but excessive use of pesticides is destroying fertility. Pesticides should not be used in pulses, but farmers are now applying them on such crops too," Gupta says. Edited by Rekha PulinnoliCover Photo - Farmer Harish Patel setting a trap to catch caterpillars (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

-6.webp&w=3840&q=75)

The rise and fall of an organic farming village in Madhya Pradesh

Malgaon in Khandwa district adopted organic practices in the aftermath of a severe drought, but things fell apart quite fast when climate change and pest attacks made cultivation difficultKhandwa, Madhya Pradesh: Olfactory discomfort is at its peak as the strong, sickening odour of pesticides and the earthy smell of cow dung waft through Malgaon in Khandwa district of Madhya Pradesh. Not a single farm in this village with 447 houses and 2,488 residents is fully organic, but that was not the case over 20 years ago.At that time, the family of Deepak Patel (37) was among the first to switch to organic practices by building three Nadep structures at their farm and another three on the premises of their house using their own resources. The family dumped organic waste in these earthen structures throughout the year to make compost.Deepak Patel believes that organic farming is a better option but organic products should get better prices in the market (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters) “Our farm was fully organic for only four years. Due to climate change and rising pest attacks, we were forced to switch to pesticides,” Deepak tells 101Reporters, while acknowledging that organic farming is the best option, provided farmers get better prices for their produce. He wants to move away from chemical-based farming, so 40% of the total pesticides used in his farm are organic now.Temikala-based Jagannath Kanade (75) has been a farmer for the last 60 years. He says predicting even the next day’s weather is a difficult task these days. “It sometimes looks like summer, then suddenly it rains or fog spreads. All these have increased pest attacks in crops. We have no option but to resort to pesticides to keep them in check.”Jagannath Kanade says that the attack of pests on crops is increasing (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)According to Kanade, farmers now spend three times more money on their crops than earlier because chemical-based farming is very expensive. In fact, more money is being spent on fertilisers and pesticides than seeds, ultimately taking away soil fertility.Even the weather forecast app is not to their aid. Durgaram Patel (35) says farmers used to get weather information on the app, but there was a problem. “The app would be showing a clear weather, but it will be raining outside. Tell me how can we decide anything in such a situation,” he asks.Young farmer Durgaram Patel talks about the uncertainty of weather and inaccuracy of weather apps (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Durgaram’s fields used to deliver 20 sacks of wheat earlier. But in the last five years, he has been getting only five to seven sacks. “If this situation prevails, farmers will have to find other means to earn their livelihood,” he warns.Farmers are fully aware that the continuous application of pesticides will make their land barren in future, but they say they do not have an option. “We have harmed ourselves by leaving organic farming. Going back to organic methods is difficult now. Farmers are trying to include some organic practices, like using 20% organic inputs. A complete switch is not easy, but it will be required to save our land,” says Kamlesh Patel (36), a farmer from Temikala.Malgaon farmer Hukumchand Patel (57) tells 101Reporters that the village did only organic farming from 2000 to 2005. “People from far and wide used to come here to learn about organic farming. I also followed organic farming during that period and got good results. Later, production decreased and the weather did not cooperate. Since the village is situated at a higher altitude, there was a water shortage. We filled this deficiency with pesticides. Within no time the situation changed and chemical-based farming increased in the entire village,” he recalls.Hukumchand Patel described how organic farming had started in the village (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Rajesh Gupta, the then chief executive officer of district panchayat, had taken special interest in developing Malgaon as an organic village and Torani as a water village. Late Hukumchand Patel was the first farmer to initiate organic farming in the village. He also informed other villagers about its long term benefits and inspired them to do the same. Patel started using the waste from his fields and house to make organic fertiliser by layering it with cow dung.In 2002, when Malgaon was a fully organic village, works to conserve water were initiated. Rainwater and nutrients flowing from flat land were stored in 7,000 water pits around the village fields. When these pits overflowed, the excess water was diverted towards the village wells. To ensure water efficiency during irrigation, drip irrigation and sprinkler methods were adopted.Earlier, even a good rainfall could not save the place from water shortage due to the high altitude and rocky ground. At that time, 505 hectares were under cultivation. There were 275 irrigable wells, but only 20 held adequate water. The severe drought between 1998 and 2000 made farmers aware of the need to change their farming practices. They understood the special role of humus and compost in retaining soil moisture, which made them turn to organic farming. Big farmers of the village built biogas plants in their homes and gave connections to their neighbours and relatives. Five big and 12 small biogas plants were built in the village in 2002. In 2012, another 218 biogas plants were built by people of the village at subsidised rates. Considering the decrease in cattle population in the village, household toilets were also connected to the plant. Close to 10 tonnes of organic fertilisers could be obtained from cow dung biogas, 8.9 tonnes from Nadep and 10.12 tonnes from vermicompost. To ensure composting in Nadep structures, 25 collection centres were set up in the village with panchayat help. Due to these efforts, Malgaon received the Nirmal Gram Puraskar in 2009. However, with cattle rearing decreasing further and people switching back to chemical fertilisers for agriculture, the biogas structures have faded away. Biogas plants have remained buried under cow dung and garbage, while not a single Nadep structure can be seen here. Now farmers collect cow dung in the open and convert it into manure. Today, only two biogas plants are operational in the village.Cow dung cakes placed on unusable biogas plants (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)As per an estimate, 806 quintals of urea, 407 quintals of super phosphate, 125 quintals of potash and 446 quintals of diammonium phosphate (DAP) are annually used in Malgaon. Pesticides to kill caterpillars and other insects are also used.(Above) Earthworm manure being prepared from cow dung (below) a hungry cow from Malgaon and the condition of biogas plant (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)“The time for caution has passed, now we should start saving what is left. High amounts of pesticides are sprayed in the fields of Khandwa. This indiscriminate use works as a tool to spoil the weather,” Dr Saurabh Gupta, meteorologist, Bhagwantrao Mandloi Agricultural College, Khandwa, tells 101Reporters. Dr Satish Parsai, an entomologist at the same college, warns that pests have become so powerful that it is difficult to kill them even with pesticides. Hence, traditional methods are more suited. “If farmers are still not alert and do not return to old methods, the future of agriculture will be even more challenging.”Malgao Sewa Sahkari Samiti distributes the government-approved urea, DAP and potash to farmers. In view of the deteriorating health of fields and soil, the government has launched nano fertiliser in the market. The society provides this also to most farmers. Krishnakant Soni showing the fertilisers (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters) “Over 500 hectares are irrigated in the village. As many as 105 farmers are registered with the samiti, which distributes 320 bags of urea, 400 bags of DAP, 150 bags of phosphate and 70 bags of potash to them. The remaining farmers in the village have to buy fertilisers from the market at a price that is four times higher,” says Krishnakant Sohni, a clerk at the cooperative society. Edited by Rekha PulinnoliCover Photo - Kamlesh Patel of Temikala sighs over how they have harmed themselves by leaving organic farming and have now come so far that it is difficult to go back (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

-5.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Devlikala learns the ropes, powers panchayat’s progress through PESA Act

The committees formed under the Act turn a pond into a better revenue generator, remove encroachments, ensure peace through quick and effective resolution of disputes and fast-track distribution of forestland leasesKhandwa, Madhya Pradesh: Tribal-dominated Devlikala panchayat in Khalwa block of Khandwa district has a five-acre pond that serves the drinking water needs of both humans and livestock and the agricultural needs. For the last 10 years, the pond has also been under fish farming by a Kharkala-based private party. The panchayat had leased out the pond for Rs 30,000 annually. But things were set to change with the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996, coming into force in Madhya Pradesh on November 15 last year. Exactly a month later, Devlikala held its first meeting to discuss names for inclusion in committees to be formed in compliance with the Act. Though the committee members had only vague answers when asked about their role at that time, they have come a long way in evaluating the village resources and taking measures to make the most out of them over the last one-year period.(Above) A picture of the encroachment (below) Panchayat Bhavan in the village (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)In one such instance, the committees managed to relieve the pond, constructed almost 50 years ago, from the clutches of a private party as its members assessed that the lessee was earning much after getting the pond year-after-year at comparatively meagre rentals. The land committee estimated that fish worth about Rs 2 lakh was reared every year without giving any fish feed.As the land committee is responsible for changes in the use of government or community land, and deals with matters of transfer, lease, contract, agriculture, sale and mortgage of land, it decided to take action. After discussions with experts, the committee took its own decision that the pond will not be given for contract fish farming. Instead, the village panchayat itself will do fish farming to generate more income that can be invested back into the development works of the village.“When other means became available, the reliance on the pond for irrigation reduced. Later, the panchayat gave it for contract fish farming. Everything went well until the contractor started to wield monopoly over the pond. The situation became such that even cattle could not access the pond in summers. When villagers complained, the panchayat did not heed to them. After the implementation of the PESA Act, we unanimously banned the leasing of the pond,” land committee member Bisu Ghisia explained. Devlikala’s PESA Act mobiliser Rohit Gautam told 101Reporters that the leaseholder prevented villagers from entering the pond. “On July 27, the sarpanch and secretary announced the pond auction. However, Dayaram Patil, the chairman of the water committee formed under the PESA Act, decided with everyone's consent that the auction should be stopped. Patil said the pond produced 20 quintals of fish. Neither fish seeds are put in nor feed given to them. The committee believes that the sarpanch and secretary are in collusion with the lessees, due to which they had been continuously making benefits,” Gautam said.(Clockwise from top left) Punaibai Shobharam, Champalal Palvi, Indrakala Kajle, Suraj Kasde, Hiralal Patil (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)The committees formed under the PESA Act also have their eyes on other resources in the village. Land committee member Hiralal Patil said they have been looking into cases of encroachment. “Eight months after the implementation of PESA Act, an individual from Malhargarh occupied a 20x40 sq ft land near the main market of the village and started construction. When the matter reached the committee, we passed a resolution against it on August 10. Subsequently, the building was demolished,” he detailed.After dealing with the encroachment, the committee members also informed Khalwa Police Station, where a case was registered against the encroacher.Ever since the PESA Act came into existence, village disputes are being resolved locally. Peace committee president Champalal Palvi told 101Reporters that the villagers were assured that all disputes would be resolved at the panchayat level ever since the committee started functioning. “This has increased their confidence. Now, village disputes are not reaching the police station. Earlier, about two to three cases used to reach the police station every month. Now, every dispute is being resolved at the local level among its own people,” Palvi claimed.Suraj Kasde, chairman, forest resource and control committee of Chikatlai in Devlikala panchayat, said the village atmosphere is better than before. “Patronage of the panchayat has also reduced. Earlier, we had to make rounds of the panchayat and go to Devlikala for even the minutest of things. Special meetings also used to be held in Devlikala only. But under the PESA Act, meetings have started to take place in our village itself.”Kasde said the sarpanch and secretary used to scold when someone asked for the accounts of work done. “In the general meeting held before the implementation of the PESA Act, when we asked for information about the gravel road built in our village, the sarpanch ended the meeting abruptly. There was an uproar, but it had no effect on the sarpanch and secretary,” he alleged. After the implementation of the PESA Act, people's work is being done at a faster pace. Kasde claimed about 50 villagers have been demanding land leases for the last 15 years. “The forest dwellers have been farming for many generations, but till now they have not received the leases for those lands. After the formation of the committees under the PESA Act, the work gained momentum. So far, leases have been approved to eight villagers,” he said.Punaibai Shobharam(64), a beneficiary, said her husband had demanded for lease until his death. But even after his death, she did not get it. After the committee came into existence, she started to get her widow pension, Moreover, she is all set to receive her lease document. “It seems as if our government has come, a government that thinks seriously about us,” she said elatedly.Devlikala has its 50% seats in panchayat elections reserved for women. Hence, the sarpanch is Indrakala Kajle, who hails from Kharkala. Like in most panchayats of Madhya Pradesh, her husband Pyarelal Kajle manages all the work. Earlier, for all panchayat-related works, the villagers had to go to Kharkala. However, after the formation of committees under the PESA Act, the villagers now have a better system in place. 101Reporters tried to contact Indrakala about the allegations raised against her, but her mobile phone was either out of network coverage or switched off. When panchayat secretary Ranjit Tanwar was contacted, he refused to reply to the allegations saying he was busy with family-related work. Read our earlier report from Devlikala hereEdited by Rekha PulinnoliCover Photo - PESA meeting of Devlikala panchayat in Khalwa block (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

_(97).webp&w=3840&q=75)

Pandemic-stricken villagers revive bamboo art with NGO help in Madhya Pradesh

Bamboo crafts bring down migration, improve access to nutrition and education, and raise morale of residents from Korku community in Gulaimal village of Khandwa Khandwa, Madhya Pradesh: Living in the remote forest village of Gulaimal in Khandwa district of Madhya Pradesh, Prakash Barole (41) crafts decorative items from bamboo to earn a living. He acquired this relatively new skill after making up his mind to stop working as a migrant sugarcane cutter and find employment in his own village.Prakash and his wife Sangeeta Barole (34) used to migrate to Beed district of Maharashtra for four months annually to work as farm labourers. Despite working for over 18 hours a day, they could barely make ends meet. During the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent lockdown of 2020, they found themselves stranded in Maharashtra with their employer denying them full wages. They were forced to return to Khandwa on foot — a journey of over 100 km — along with 10 others from their village. They had no money, not even to buy food.“We both used to get Rs 10,000 per month, but we did not even have a day off. Most of what we earned was spent on lodging and food,” he recalls. “Just 10 days into the lockdown, our employer told us that he could not pay us anymore.”Prakash then decided to fend for himself in his own village, even if it meant learning a new skill in his late 30s. His determination paid off as both earn around the same amount every month by making bamboo items for Gulaimal-based non-government organisation (NGO) Manmohan Kala Samiti (MKS). “We work for eight hours daily and get a good price for our work,” says Prakash, who saves a large part of his income and manages to send his children to school.Bamboo collected outside the centres (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Seeds of changeThe NGO was established under the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) and operates under SFURTI (Scheme of Fund for Regeneration of Traditional Industries) of the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, which assists traditional industries such as khadi, coir, handloom and handicrafts by providing grants of up to Rs 5 crore. The NGO set up operations in the district in 2020 under the nodal agency Council for Handicrafts Development Corporations. A Bamboo Craft Centre was established, with a 90% Central grant under SFURTI and the remaining investment from MKS.Of the 150 families employed by the NGO in Gulaimal, about 60 work directly at the bamboo centre. The rest make the products at their homes. Most of them are Korku tribals. The centre purchases the bamboo planted by village farmers at a price equal to the minimum support price. Until the establishment of the centre, around 40% (1,100 people) of the village population used to migrate for work.Pradeep Awase (27), a resident managing the bamboo art work under MKS, used to go to Pune. “I worked at a local furniture firm. Most of what I earned was spent there and despite having worked with the employer for a long time, I was deserted when the pandemic struck. I was forced to walk back home. The employer did not even bother to arrange a transport facility for me,” he says. Pradeep joined MKS and honed his management skills in the last three years. He now imparts training to new artisans and organises local craft exhibitions with the help of MKS.According to a survey conducted by the NGO, migration has reduced by half since its inception, as the locals earn a monthly salary of Rs 6,000 to 8,000 at the centre. However, not all villagers are into bamboo crafts. Due to the surge in bamboo-related work, other trades and businesses have increased in the village, thereby providing a source of employment to many .To increase their income further, locals have started planting native bamboo varieties such as Katanga (Bambusa Arundinacea) and Deshi (Dendrocalamus Strictus) on the margins of their fields under the guidance of MKS. This will reduce the need to get bamboo from other villages. When needed, the MKS also provides them with bamboo seedlings.Furniture, toys, home decor, reception, office and coffee house items are produced at the centre and sent to NRLM sales centres. They are also exported. MKS director Mohan Rokade tells 101Reporters that the NGO expanded to accommodate more artisans in 2021 and that its annual income has soared to above Rs 50 lakh. “Bamboo craft has been a part of the village culture for generations. But people were making only specific items such as mats and baskets that were useful to the village community. When the availability of bamboo reduced, people migrated in search of employment. After the NGO formation, we distributed bamboo seedlings to the locals at a minimal cost, leading to a surge in bamboo production,” Rokade says. Earlier, farmers sold their bamboo to the forest department or in the market. Raju Vaskale, a farmer from Dhimaria, located four km from Gulaimal, says he now gets money immediately after selling bamboo unlike in the case of the forest department. "We do not have to bear transportation costs as the centre collects bamboo from our fields. Katanga bamboo is priced at Rs 80 in the market, Deshi at Rs 100 and Assamese bamboo at Rs 220. We get the same price from the centre," he says.Prakash has also planted bamboo saplings on his two-and-a-half acre plot. He plans to sell it to MKS. Apart from Gulaimal, bamboo clusters are functional under SFURTI at Hoshangabad, Betul, Chhindwara, Balaghat, Seoni, Ratlam and Burhanpur. Last year, Harda district was included in the cluster. Bamboo craft serving as a livelihood opportunity for the community (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Life gets betterWhen she migrated to Beed, Sangeeta used to leave her five children in the custody of their grandmother Lalitabai. This affected their studies as the older children would often be occupied with taking care of their younger siblings and miss out on school.“I at least had my mother-in-law to help out, but the mothers with newborns and those with children under five years of age had to take them along when they migrated. Life as a farm labourer is difficult. Sometimes, we have to survive on just one meal. So, even the babies could not be fed since the lactating mothers barely ate,” highlights Sangeeta.New mothers who were forced to quit work due to these challenges are now joining the NGO as it has a secure campus for children with proper facilities and caretakers. The centre is spread over five acres of land, where a factory has been built on an acre.“Since new and expectant mothers can stay in the village and make bamboo crafts, they have also registered at local anganwadis, thus bringing them under the government's nutritional programmes. They get fortified milk powder and nutrition-rich food from anganwadis,” she adds. Young women who used to be either married off right after school or were forced to join their parents as farm labourers are now enrolling in colleges to find well-paying jobs. “Working on the field with my parents was tiresome. We did not even have enough to fulfil our basic needs, so college was a distant dream. But now I work with the NGO, while pursuing my post graduation in commerce from an open university,” says Usha Barole.Madhuri Awase and Aarti Barme earn Rs 7,000 each and are able to keep some money aside for their children’s education. Even specially-abled people have got a chance to earn through the NGO.The products such as table lamps, clocks and showpieces produced by the company were showcased in the Parliament House, New Delhi, and exhibited at the Dubai Expo alongside products from 190 countries last year. Artisans add that they were not skilled at anything and were looked down upon, but they enjoy a newfound respect in their communities and feel proud of the work they do when their handcrafted products are admired at both local markets and international exhibitions."Once awareness about the sustainability of bamboo products versus plastic pollution increases, and the new electricity grid comes into operation, I think we will be able to expand operations and hire more people," says Rokade. Edited by Shuchita JhaCover Photo - Women weaving bamboo articles (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

_(82).webp&w=3840&q=75)

How a 77-km bus service revived the age-old Harbola tradition in Madhya Pradesh

A bus that runs once daily has transformed lives by enabling job opportunities, education access and strengthening community tiesKhandwa: An overcrowded bus winding through a narrow road is among the first images that pops up when one thinks of a rural landscape. Such buses not only serve as the lifelines bridging the gap between remote regions and urban centres, but also do much more, as in the case of the Harbola community of Madhya Pradesh. Living in the remote villages of Nimar region, especially in Khandwa district, the Harbola people have been traditionally into singing. Thanks to Subhadra Kumari Chauhan’s famous poem Khoob Ladi Mardani, depicting the valour of ‘Jhansi Ki Rani’ Rani Laxmibai as narrated by the Harbolas, the word about the community had spread before Independence itself.Poornima says the bus is why she has continued her further studies (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters) However, despite their talent, most of the community members had to take up agricultural jobs to make ends meet. A new ray of hope emerged when a private bus started plying from Baldua Dongri in Khandwa district to Jhirniya in neighbouring Khargone district, covering a total of 77 km via Sawkheda, Mundwada, Sihada, Khandwa and Pandhana (NP). “Earlier, my wife and I used to work as farm labourers to make ends meet. At times, in the rainy season, we faced starvation too. Ever since the bus started plying, I have not done anything but sing, accompanied by tumdi-kartal [both folk instruments],” Atmaram Nainsingh (58) of Baldua Dongri village in Khandwa district tells 101Reporters, while waiting at the bus station in the city.Over 200 people from seven nearby villages benefit from the service. At 8 am every day, the bus starts from Harbola Bahul Basti (a Harbola-dominated residential area) in Dongri-Kurwada. It reaches back to the starting point by 6 pm. One trip on the bus costs Rs 120 end-to-end. There is no government-run public transport between cities in Madhya Pradesh.With bus plying, the Harbolas leave the village for two to three weeks at a stretch and earn money by performing at tourist spots. “We start to move out after Deepavali (October-November) and travel from place to place, singing in open areas to attract locals… We continue to do so until Holi (March),” says Dharamlal Sunderlal, another villager who was returning home after touring the state for a week along with Nainsingh.When the bus wasn't operational Atmaram's family was starving (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)“Not every day is a good day, sometimes we do not earn enough or not at all… When it gets tough, we step out at 5 am and beg on the city streets. We sleep at the bus station or near the overbridge,” he adds.“This is because their folk music has not received the respect it deserves. The government encourages other art forms and provides them a platform abroad and in the country. Tumdi- kartal artistes should also be respected,” says Rajan Ranhe, another village resident.The roots of tumdi-kartal music run deep “Earlier, the Harbolas used their art to communicate messages between kings and inspired the locals to take part in the freedom movement by narrating stories of prominent freedom fighters,” he adds.Rajan Ranhe says government should encourage art forms (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)The Harbolas fall under the category of Other Backward Classes and live in clusters in Bundelkhand area as well as Khandwa district. Baldua Dongri sarpanch Pancham Manidhar tells 101Reporters that around 8 lakh Harbolas are present across the country. Of them, about 5,000 live in Khandwa district. In addition to singing, they also work at farms and construction sites.“Our community moved here from Bundelkhand about five generations ago. Since then, we have been earning income by singing paeans to kings. Due to economic disparity, we are forced to beg to make ends meet. Whatever they manage to earn is only because of the availability of bus to Khandwa,” Rahne says.“There are periods during which travelling for 20 days a month can earn us enough to rest at home for the next 20 days,” says Nainsingh, who supports his family of seven with tumdi-kartal singing. His elder son works as a farm labourer to supplement the family income.Antar Singh Parihar of Khargone says the bus has reduced the distance between people (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Social glue“The 8 am bus is the only mode of transport that connects Goradiya, Sawkheda and Mundwada villages with the rest of the state,” Antarsingh Parihar (75) of Khargone district tells 101Reporters. He was on his way to visit his daughter in Goradiya. “My daughter Santoshi’s mother-in-law met with an accident. I am going there to enquire about her health. When my daughter got married in 2016, reaching Goradiya located 27 km away was a big task. Now, there is no such problem. I would say the bus service has strengthened the relationship between the two families,” Parihar says.Purnima (21), who boarded the bus from Khandwa to reach Sawkheda located 15 km away, says she was able to continue her studies because of the bus. Purnima is in the final semester of her BA programme at the Government Girls Degree College in Khandwa. “The bus provides a safe environment for girls to travel. The villagers have faith in the bus drivers and conductor. They take care of us like family,” she says.The bus service has also enabled jobseekers. Sumaila Bano (23) from Mundwada now works as a teacher in a private school in Khandwa, located 11 km away. She earns an honorarium of around Rs 3,000 per month. With this income, Bano plans to continue her education, which will eventually lead to a higher salary at a higher teaching position. “It would not have been possible without the bus,” she says.Dharamaraj Bansor from Baldua Dongri shares that before the bus service, villagers were confined to their place due to a lack of transport facilities. Many owned land and earned through farming, while others found work as labourers in nearby villages. “Bus service has enabled people to travel to Khandwa for employment opportunities, improving their quality of life,” he says.According to Manidhar, the largest chunk of the population of the community lives in Benpura Kurwada, totalling around 1,200 residents. Additionally, 200 people live in Madni panchayat, 350 in Badgavmal, 400 in Baldua Dongri within Mathani panchayat and 2,000 in Bainpura-Dongri. Among these, only Baldua Dongri has a bus service connecting to Khandwa. Edited by Tanya ShrivastavaCover Photo - Dongri bus that transformed lives (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

_(13).webp&w=3840&q=75)

Once a worker, now an intruder: How tribals lost the ‘plot’ in Burhanpur

Brought here generations ago by the British to clear forests, local tribals are looked at with suspicion and accused of abetting encroachments in the recent yearsBurhanpur, Madhya Pradesh: Khandwa forest circle encompassing the districts of Khandwa, Khargone, Barwani and Burhanpur has always been a hotspot of encroachment. According to May 2005 data from the forest circle, 58,000 hectares were totally encroached upon in these four districts. However, the volume of encroachment in Burhanpur alone soared to 55,000 hectares by 2017. Originally, the district had an expansive forest cover of 1,90,100 hectares.Burhanpur forest division has seven ranges, of which maximum destruction happened in Nepanagar, Navra and Asirgarh. The forests in Ghagharla, Siwal, Bakdi, Pankheda, which fall under Nepanagar and Navra ranges, took the most beating. According to state forest department, 1,623 hectares coming under Navra range went to encroachers since 2018. Of the total 21,716 hectares in Nepanagar range, 6,806 hectares were occupied. Notably, encroachment has intensified in the last few years, which set the context for disputes between the old settlers and the new encroachers. In the process, Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangathan (JADS), which works for tribal welfare, threw its weight behind the old settlers and nudged the district administration and forest department to take action against the new encroachers.However, the administration got its act together only after the Nepanagar Police Station attack in April. But when it did, it acted against all the parties concerned. On May 1, the JADS also faced the heat when a case under Section 66A of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, was registered against eight activists, including its leader Madhuri Ben.The history of tribals in Nimar (now Khandwa) circle dates back to the time of the British rule. In 1878, the British passed a forest Act, which was designed not to nurture the green cover but to chop it down. Nimar Gazetteer has details of how Bhil tribals from Barwani district were brought to Mandwa (now it falls in Nepanagar tehsil) to cut the forest. There was no human presence here until the tribals made it their home, which showed tribals were not the original inhabitants of the place. Nepanagar town was also established on the forest land, and so was a newsprint paper mill in 1956. Divided they standRight now, those occupying the forests are divided into two groups — the local tribals who have been living here for many years and those who have been here since a few years ago. The second group allegedly cut down several acres of forests in a single night, thus fostering a hostile environment in the region.Local tribal Umakant Patil said the new settlers entered the forest in groups, fell trees and set them afire. “Sometimes, this fire reaches our fields . We want to save our forest, but the department staff do not cooperate.”Chhayabai, another local tribal, said the encroachers were often seen on the forest edge. “They cut trees standing next to our fields, which essentially prevents us from nurturing our crops. My gram crop on five acres got damaged and could not be harvested in time,” she lamented.Ram Jamra of Bakdi was not ready to speak at first. When prodded, he narrated how hundreds of people swarmed the forest in the dark of the night and how the locals immediately passed on the information to the department, but no action followed. "Forest department staff are scared of these attacks. They do not have the right to use weapons. Police and Army personnel are seen accompanying them during anti-encroachment drives," he said. (Above) Ram Jamra of Bakdi; (Below, from left) Bishan Vaskale and Gendalal Sisodia (Photos - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Gendalal Sisodia (70) settled in Chainpura village under Badnapur panchayat in 1977. Until 1980, the forest department registered eight cases against him. Though the court acquitted him in all cases, the department did not consider his application for the grant of patta. He claimed his name was dragged into last year’s Mandwa incident, which threw him in jail for seven months straight.“All this because I have been fighting not only for my rights, but also for my fellow tribals in my capacity as a JADS worker… I have not lost my courage; as long as there is life in this body, I am not going to leave this forest,” he stated, adding that only one out of the 130 people who applied for lease got approval. Ranchhad Richu's application was okayed eight months ago, and he had submitted only the same documents that others did. Bannu Vaskale of the same village applied online in 2020 as his earlier claim got rejected. “I have not heard about it till date,” he exclaimed. Showing his lease application, Dhansingh Richhu added, “We have been living here for generations, but the department staff look at us with suspicion.”In the absence of Badnapur panchayat sarpanch Rukmabai Vaskale, her representative Bishan Vaskale told 101Reporters that the claims were rejected citing errors. “The revenue and forest officials do not cooperate for the proposal and verification of claims. The panchayat will continue to support the tribals fully. We are with them in this fight.” The panchayat has a population of over 1,200, including 823 voters. People have settled here before 2000, and are eligible for pattas promised by Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan in the run-up to the 2016 Nepanagar bypoll and 2018 state Assembly elections. With the next Assembly elections set for this year-end, villagers expect more hollow assurances sans necessary action.On the boilOver the last three years, the forest department and villagers have been at the receiving end of attacks, allegedly perpetrated by the encroachers. On July 5, 2020, an incident of stone pelting was reported in Ghagharla, followed by unruly incidents on July 19 and August 7. Subsequently, an anti-encroachment campaign involving 350 administrative staff was launched in Ghagharla on November 7. Seventeen of them suffered injuries in the violence that ensued, which included snatching of weapons. On July 2, 2021, forest staff in Dahinala north under Asirgarh zone faced the wrath of encroachers. A few months later, on November 21, a police team that went to arrest an accused in the dead of the night was attacked at Chidiyapani, an encroachment site in Nepanagar. In the most recent incident on April 7, over 60 tribals attacked the Nepanagar Police Station and freed three arrested men from detention.(Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)“This (police station attack) is a well-planned conspiracy. Even after the incident, the administration did not act swiftly. First, they said the accused have ventured deep into the jungle, so we cannot reach them. Then they launched action against the villagers, arguing that they colluded with the encroachers,” JADS leader Madhuri Ben told 101Reporters.Reiterating that all tribal settlers in the forests have been staying here for many generations, she claimed indiscriminate felling has intensified in the recent years. “According to a survey we did to draw attention of the administration, about 15,000 hectares of forest were found to have been destroyed since October 2022, which cannot be termed practical at all. The forest department has a role to play in this,” she alleged.Refuting the allegations, Anupam Sharma, who was the divisional forest officer when the police station attack happened, told 101Reporters he had asked the JADS members to name those they believed were part of the conspiracy and also provide evidence. "However, they provided us neither any name nor proof. It is clear that the allegations are baseless." On the alleged loss of 15,000 hectares, he said "the forest has not been cut as much as they are telling, but there is no denying that it has been cut." Elaborating on the JADS stand on the matter, Ben said, “We oppose the new encroachers who not only destroy the forest but also trouble local tribals and unleash attacks on forest staff. Our organisation is taking along those who have settled here before 2000. I would say they have strong evidence to show, as even the cases filed against them by the department in the earlier days can prove the timeline of their stay here.” Madan Vaskale (Photo - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)Madan Vaskale, a member of the Bhil Samaj, is among those claiming the right to land. “The forest is our temple, our means of livelihood. Mahua, charoli and tendu patta from the forest earn us a living. Our cattle feed on forest resources. Thousands of acres of forest would have been thriving with life, had the department acted on our complaints. There are people who clear the green cover and attack forest staff. But, we protect it by staying within the ambit of the law. In return, we are demanding our rightful land from the government,” Vaskale appealed. Edited by Rekha PulinnoliBurhanpur's deforestation crisis boils over. Read our report from April about how things came to a headRead about the Administration's seemingly arbitrary and disproportionate response to the violence and protests Cover photo - (From left) Bannu Vaskale, Dhansingh Richhu and another resident with their applications for land pattas under the Forest Rights Act (Photos - Mohammad Asif Siddiqui, 101Reporters)

Loggers have a field day in Burhanpur, but police, forest departments have an axe to grind