Families in Rajasthan are pushing back against Mrityu Bhoj

Families in Rajasthan are pushing back against Mrityu Bhoj

Instead of spending lakhs on funeral feasts, some are redirecting the money to schools, libraries and community projects despite caste panchayats continuing to enforce the costly custom.

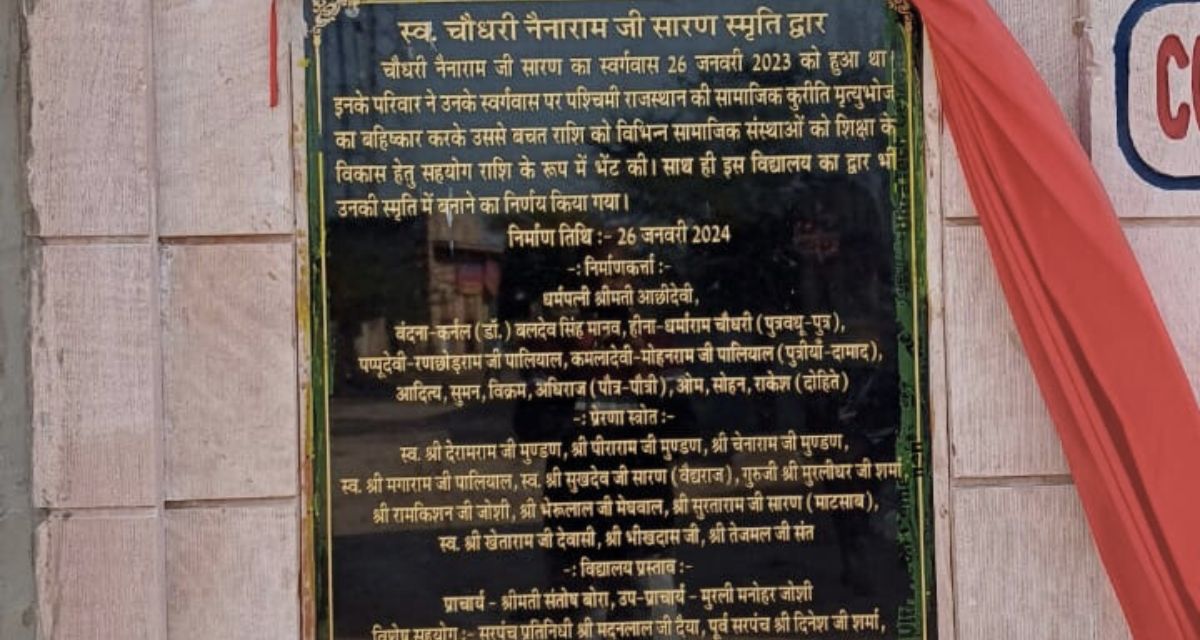

Sriganganagar, Rajasthan: When Colonel Baldev Singh "Manav" Chaudhary’s father, Naina Ram, died in Devgarh village near Balesar in Jodhpur district last year, he and his younger brother Dharamaram made a decision that went against long-standing social custom. They chose not to organise a mrityu bhoj – the ritual funeral feast that often runs for days and feeds thousands of people.

Instead, they redirected the money, about Rs 22 lakh, to fund libraries, schools, cow shelters and cremation grounds.

“If we had continued to have feasts till the thirteenth day, it would have cost many lakhs to feed thousands of people,” Colonel Chaudhary said. “In 1982, my father had to mortgage household jewellery to arrange a funeral feast for my grandfather, despite a severe famine. It disrupted my education. From then on, I vowed to oppose this practice.”

In Rajasthan, death rituals are accompanied by several customs, the most prominent being mrityu bhoj. For generations, the feast has been seen as a marker of prestige and honour.

Ganga Ram Jakhar, former Vice Chancellor of Maharaja Ganga Singh University, explained that the custom dates back to feudal times, when it was known as kansa lag. In those days, the bereaved family would send food in bronze vessels to every household in the village. Later, the practice shifted to large gatherings at the family’s home, where the wealthy would feed thousands, which became a display of prestige. For poorer families, however, it became a compulsion.

Jakhar noted that in western Rajasthan, a single mrityu bhoj can cost anywhere between Rs 7 lakh and Rs 20 lakh. In some cases, families host mourners from 10 to 20 surrounding villages.

The financial toll

The cost of these feasts has left generations in debt. Families mortgage jewellery, sell land, or borrow heavily to meet the expenses. Children often drop out of school when resources are diverted. Colonel Chaudhary, who campaigns against the custom, said that families already drained by medical expenses for elderly relatives are then pushed into debt by mrityu bhoj. “To repay this debt, children are forced into labour. It also encourages child marriage. In Marwar, more than half of such marriages are solemnised on the occasion of Terahvi Rasm,” he said.

Jakhar added that the interest on loans taken for feasts is often unmanageable with ordinary incomes. “Families lose savings, sell land, and children miss school. The economic impact is devastating,” he said.

In recent years, however, more families are making different choices. Dharampal Sihag of Pallu village in Hanumangarh district donated the amount he would have spent on a feast for social causes after his father’s death. In Ghana village of Jalore, Rooparam’s family donated Rs 5.25 lakh towards building a girls’ hostel. Retired Director General of Police SR Jangid donated Rs 9 lakh to educational institutions after his sister-in-law’s death in Barmer. In Payala Kalan, Balotra, Genaram’s family redirected their resources to education.

Social pressure persists

Despite these examples, social pressure remains intense. Caste panchayats continue to enforce the practice, threatening boycotts and fines. In many villages, those who refuse to organise mrityu bhoj risk expulsion.

Padmaesh Sihag, who leads an anti-mrityu bhoj campaign, explained that panchayats even provide loans to ensure families can host feasts. The gatherings last twelve days, with elaborate menus and along with the customary serving of opium and poppy husk. In Marwar, offering these intoxicants is an old tradition and is usually offered with food at feasts.

Those who resist face punishment. Panchayats announce a “hukkaa-paani bandh”, which literally translates to cutting off hookah and water, but symbolically means a complete social boycott. Once such a declaration is made, the community severs all ties with the person. Cases of hukkaa-paani bandh are reported from districts including Jodhpur, Barmer, Balotra, Pali, Bharatpur, Jaisalmer, Jalore, Sirohi, Nagaur and Chittorgarh.

In Balotra’s Maylawas village, Deeparam Dewasi said he and others who opposed the custom were expelled from their caste. “The panchayat announced that anyone who had contact with us would be fined fifty thousand rupees and a sack of millet,” he said. Panchayat members demanded fines of Rs 5 lakh each to reinstate them. Devasi claims that two of us paid the fine, while we are still facing the boycott. Meanwhile, caste Panch Gilaram denies these allegations. He said that it is true that Dewasi had stopped about a dozen funeral feasts, but they have not taken any action against him.

Legal response, campaigns and social movements

Notably, Rajasthan was the first state to criminalise the practice with the Mrityu Bhoj Prevention Act, 1960. Yet the custom persisted, driven by social enforcement. This year, following petitions from residents of Jalore, Nagaur and Gotan, the Rajasthan High Court set up a five-member commission to investigate caste panchayats.

Advocate Ramavtar Singh Chaudhary, a member of the commission, said they have visited ten districts so far. “We found that caste panchayats are brutally harassing people, forcing them to spend lakhs on funeral feasts, declaring hukkaa-paani bandh (social boycott) if they refuse, and even imposing arbitrary fines in marriage matters,” he said. The commission will submit its findings to the court.

The court will likely ask the government to enact a separate law to deal with such cases, Singh Chaudhary said.

But the state has been opposing the practice for many years.

The first strong opposition to mrityu bhoj came from Nagaur about 25 years ago, eventually leading to statewide campaigns. Two decades ago, when Sihag from Hanumangarh refused to hold a feast for his uncle, his family opposed him, but his efforts sparked the “Leave the Mrityu Bhoj” campaign. Today, around 200 workers associated with it have persuaded 26,000 people across 17 districts to pledge against funeral feasts.

Groups like Jaipur’s Johar Jagriti Manch are also spreading awareness. Villagers now not only refrain from hosting feasts but also approach the police when caste panchayats coerce them.

However, Jakhar said that campaigns have changed attitudes in 20-30% of cases, but wider change requires people themselves to stop participating. “The biggest problem is those who go to eat,” he said. “If people stop attending, there will be no need to organise the feast.”

Dr Archana Godara, a sociology professor in Hanumangarh, calls the feast a “deeply ingrained social evil.” While direct bans face resistance, she suggested encouraging alternatives. “If villagers are guided to spend the money on schools or social causes, change is more acceptable,” she said.

As Sihag puts it, “This is not just a cultural issue. It is about economic and social improvement. If money goes to schools instead of feasts, everyone benefits.”

This story is part of our series, 'Last Rights, Lost Rights,' about death in rural India and what it reveals about caste, class, migration, governance, and ecology.

Cover image - In Lakhoniyo village in Barmer district, family members plant saplings in memory of their elderly mother, after donating the money intended for her mrityu bhoj (Photo sourced by Amarpal Singh Verma, 101Reporters)

Would you like to Support us

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All NewsAbout the Reporter

Write For 101Reporters

Would you like to Support us

Follow Us On