In Maharashtra, cane-cutting women are the healthcare lifelines for migrant communities

In Maharashtra, cane-cutting women are the healthcare lifelines for migrant communities

In drought-hit Marathwada, women trained as Arogya Sakhis are providing first aid and medical support to thousands of migrant families left behind by the public health system.

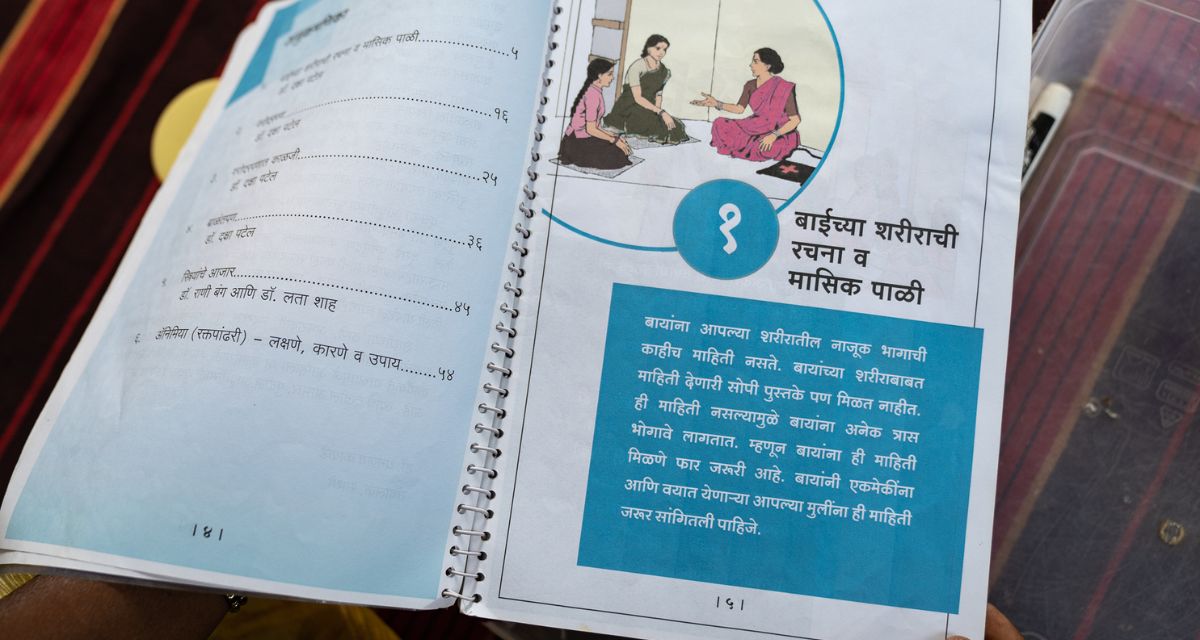

Beed, Maharashtra: “Many women use chumbal, the cloth we tie on our heads to carry sugarcane, as a sanitary pad during our periods,” Sadhana Waghmare (32), a cane-cutting labourer from Maharashtra’s Beed district said. “While on the field, we have no time or safe place to wash or change clothes in the fields, so we continue using the same cloth. This causes itching, swelling and infections. Earlier, we had no one to share this with. Now, because of the Arogya Sakhis, at least someone listens and suggests solutions.”

In 2023, Waghmare was among 20 women trained under the Arogya Sakhi programme, a community health initiative for migrant cane-cutters in drought-prone Marathwada region. Every harvesting season, thousands of families migrate to work in the fields of western Maharashtra and beyond, with little access to healthcare.

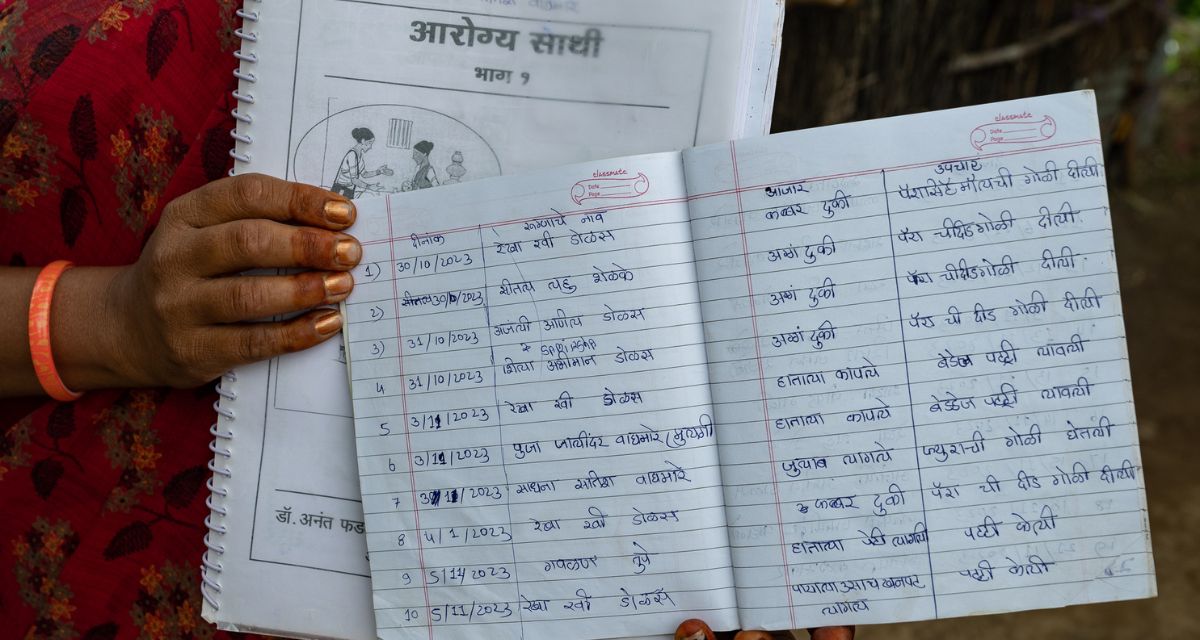

The programme – run by Society for Promotion Participative Ecosystem Management (SOPPECOM) and Anusandhan Trust Sathi – was born out of the Covid-19 pandemic, when SOPPECOM distributed notebooks to migrant workers to track their injuries, illnesses and health expenses during the lockdown.

The data showed that basic health training for volunteers could help reduce medical emergencies.

Arogya Sakhis are trained to offer first aid and distribute non-prescription medicines from standardised kits, with supplies provided by the Beed Zilla Parishad. The kits include essentials like paracetamol, oral rehydration salts, antiseptic lotion and cotton dressings.

While the women work as volunteers, they receive a travel allowance of Rs 500 when applicable. To qualify, participants must have studied up to at least Class 7 and be literate. The initial seven-day training covered first aid, menstrual hygiene, and record-keeping, while subsequent batches received a condensed four-day version.

Though many early trainees were cane-cutters with limited education, support from trainers in Pune helped them overcome unfamiliar medical vocabulary. Over time, they gained confidence and began offering health support not just at field sites but also in their home villages.

By the second year, the programme’s impact was visible. Volunteers were also representing their communities in Jana Aarogya Samitis or village health communities with the help of local grassroots groups like Mahila Ustod Sanghatana helped coordinate this outreach. “There were no health services at the migration sites,” said district convener Manisha Tokale. “We realised that if even one woman in each group was trained, she could help others and connect them to care when needed.”

Cycle of neglect

During the migration season, labourers shift in pairs called koyta, typically husband and wife, and are paid Rs 350 to Rs 400 per ton of sugarcane cut. They are expected to meet a daily target of two tons which helps them get Rs 800 a day per pair. And, taking even a single day off, including for medical reasons, invites a penalty of Rs 1,200 from contractors. As a result, many workers continue cutting cane while unwell.

“These contractors are least bothered about the workers’ health or rights,” Ashok Tangade, president of the Beed District Child Welfare Committee said. “The government says India is free of bonded labour, but sectors like sugarcane and brick kilns still practice bandhua majdoori. The contractor, farm owner and sugar factory are all responsible for providing medical facilities, but they shirk these responsibilities completely.”

As a result, Tangade said, labourers are squeezed from both ends: unable to afford medical care and punished if they try to access it. “They work through illness, risking long-term harm. They compromise on nutrition, healthcare, even their children’s education and vaccinations,” he added.

These labourers belong to Marathwada, a drought-prone region in central Maharashtra, comprising seven districts. The region lies in the rain shadow of the Western Ghats. With poor irrigation and limited industrial development, farming here is usually restricted to a single, rain-fed crop each year. As a result, thousands of families migrate annually to western Maharashtra and to other states such as Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu for sugarcane-cutting work.

This pattern of migration began after the 1972 drought and has continued for over five decades. In many villages, the children of cane-cutters grow up expecting to follow the same path.

From Beed district alone, over 10 lakh people migrate for the harvest season each year. Of them, more than 3 lakh are women, according to civil society estimates.

A voice in the system

Over time, Arogya Sakhis have become important intermediaries between migrant women and the public health system, not just by treating symptoms, but by helping women articulate their needs and push for better access to care.

Volunteers like Waghmare and Kalpana Thorat have repeatedly raised the demand for sanitary pads at Jan Aarogya Samiti meetings, even if the response has been slow. “I have raised the sanitary pad issue with the Sarpanch before every migration season,” said Thorat, a cane-cutter from Pimpalwadi village. “He always promises, but we never receive anything. Even the ASHA worker in our Samiti could not help.”

Despite this, Thorat said she felt empowered to speak up. “It is a major issue for migrant women. I am glad I was able to bring it up in front of the Samiti, which includes the Sarpanch, Community Health Officers, Primary Healthcare Centre nurses, Anganwadi and ASHA workers, and SHG members.”

Her efforts are recognised by others in the community. “Every village should have someone like an Arogya Sakhi,” said Shahnaj Ajbuddin Sayyad, president of the self-help group in Pimpalwadi and a member of the Samiti. “I worked as a cane-cutter for 15 years. The ASHA worker gave us medicine sometimes, but her visits were irregular, and our work was unpredictable. With Arogya Sakhis we have a constant connection.”

Bridging language and distance

Waghmare recalled the difficulty of seeking care in unfamiliar places during migration. “In Karnataka, my younger daughter was suffering from Unhali, a condition where you need to urinate frequently in summer,” she said. “For the first four hours at the clinic, we couldn’t explain the issue to the doctor, we didn’t speak Kannada, and the doctor didn’t understand Marathi. A translator from a nearby village finally helped.”

In another case, she said, an elderly woman from her village used to travel 10 km to Beed just to get medicine for fever. “Now, for the past two years, she doesn’t need to. She gets the medicines in the village itself,” Waghmare said.

The effectiveness of the Arogya Sakhi training becomes most evident during emergencies. “One fellow labourer’s leg was cut by a metal sheet,” said Thorat. “I was able to stop the bleeding with the first-aid kit. He later got eight stitches from the doctor.” The illustrated manuals and labelled kits, she said, helped her identify the correct medicine for each condition.

“The sharp sugarcane leaves and the koyta often cause hand injuries,” Thorat added. “The Band-Aid strips have been really useful. Paracetamol helps with period pain, otherwise, the contractors don’t allow rest during those days.”

Her work has extended beyond the fields into her village. “Recently, my grandson got a cut on his foot. We were planning to take him to a private clinic, but by evening my son called me. I dressed the wound, and it saved us money,” said Shantabai Pakhare, a 50-year-old villager from Pimpalwadi. “Kalpana has helped us many times, especially when the PHC is closed at night.”

The programme has also led to visible cost savings. “We used to spend Rs 25,000 during harvest season on medical expenses,” said Waghmare. “For the last two years, we’ve saved that money with the help of the Arogya Sakhi kit.”

During one migration, she said, she provided medicine to four tolis, about 40 to 50 people. After returning home, another 20 people from her village also benefited from the same kit, which contains paracetamol, Flura, Dome, cotton bandages, wool, Gentian violet antiseptic lotion and other over-the-counter medicines. “I can now treat fever, diarrhoea, dehydration and minor injuries, and do basic bandaging,” she said. “This has helped both my own toli and others at the migration site.”

Changemakers

Arogya Sakhi training hasn’t just improved healthcare access, it has helped cane-cutting women emerge as local health leaders. Many are now pushing for systemic change.

The Mahila Ustod Sanghatana demanded that cane-cutting workers be included in the Jan Aarogya Samiti during the October-April migration season, so healthcare support continues in their villages while they’re away. These demands were raised in women’s assemblies and later passed in Gram Sabhas.

In 2021, SOPPECOM began documenting the Arogya Sakhis’ work. By 2022, it encouraged women to seek representation in the Samitis. In 2023-24, the key demands included Samiti membership and identity cards for migrant women.

The Zilla Parishad initially resisted, citing budget constraints. But health advocates argued that representation would improve access to schemes, health camps and sanitation drives, and bring migrant women into the public health system.

Identity cards, to be issued by local bodies, would formally recognise cane cutters and help them access aid during migration. Signature campaigns and follow-ups were carried out with the Chief Minister’s Office and the District Health Officer. Lists of trained volunteers linked to PHCs were submitted.

Despite early pushback, 28 Arogya Sakhis in Beed and 24 in Hingoli now work at the Gram Panchayat level. According to SOPPECOM, each migrant family saves an estimated Rs 25,000-Rs 30,000 per season on healthcare due to their work.

Ahead of the 2024–25 season, the Beed Zilla Parishad organised refresher training and distributed new kits, which the Arogya Sakhis say lasted them beyond the migration period.

“I’m hopeful that thousands of trained women can work as Fadavarchi ASHA and support the 3 lakh women who migrate from Beed,” said Manisha.

Now, the administration is planning a new initiative: Arogya Mitra. Each migrant group will have a trained volunteer to coordinate with ASHA and Anganwadi workers. Training is expected to begin in August.

Former Zilla Parishad Chief Executive Officer Aditya Jivane said such women can offer first-line care, promote nutrition and immunisation, and help link remote camps to the health system.

Cover Photo - Kalpana Thorat, Arogya Sakhi and Shantabai Pakhare showing the medical kit given to Arogya Sakhis (Photo - Abhijeet Gurjar, 101Reporters)

Would you like to Support us

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All NewsAbout the Reporter

Write For 101Reporters

Would you like to Support us

Follow Us On