Torn between trouble-ridden forest home and prospect of better life, Barnawapara villagers in flux

Torn between trouble-ridden forest home and prospect of better life, Barnawapara villagers in flux

Living inside a protected sanctuary is becoming harder for people of the 18 villages here, but relocation is not an easy option either

Balodabazar,

Chhattisgarh: As a student, Manoj Ugre memorised his

lessons with his friends in the light cast by a lantern. Now, in his 20s,

electricity still eludes his village Bar, located inside the Barnawapara

Wildlife Sanctuary in Balodabazar district of central Chhattisgarh.

Ugre wants

to relocate elsewhere for better opportunities and many of his fellow villagers

share his sentiment. “Shifting is preferable as crop damage by wild animals is

high here,” he said, adding that places near Patewa village in adjoining

Mahasamund district were desirable as they had good roads and electricity.

However,

the population of Bar is divided over the issue of shifting. Warning that it involved

internal politics, Rajim Ketwas of the Dalit Adivasi Manch said, “Some people,

especially the Agaria community, are eyeing

government compensation for voluntary relocation. They want to settle in cities.

But the adivasi folk, the original settlers, have sizeable

lands here.”

Such

people do not want to leave, despite the problems. In Bar, people owning lands are mostly into paddy cultivation. Farmer Naresh Yadav has five acres of land and is always apprehensive

about crop damage by wild elephants.

In

addition, they have to make do with solar power that

lasts only for a few hours daily. Not just electricity, the

place does not have proper roads and mobile connectivity as it comes within a

protected forest area. “The villagers cannot construct homes; they cannot collect

forest produce freely; and even the sarpanches find it difficult to run the

panchayat,” Ketwas listed out the problems.

Bar

resident Rajkumar Diwan said the village has no good schools. “We have to

either send our children to Balodabazar or Mahasamund. Most families cannot

afford it,” said Diwan, whose son works as a teacher in Mahasamund district.

Diwan owns

two acres of land suitable for paddy cultivation. The landless here are engaged

in labour work.

“Some people tried to relocate a decade ago, when three other villages were resettled. But that did not happen,” Diwan said, referring to the relocation blueprint that was put down.

Bar resident Rajkumar Diwan says the village has no schools and his paddy crops are under constant threat from wild animals; (right) Rampur residents have no electricity and have to use solar lamps that last only a few hours into the night (Photos: Deepanwita Gita Niyogi)

Settling

down elsewhere

In

Barnawapara Wildlife Sanctuary, the relocation of 20 or so villages located inside

the forest was put in motion almost a decade ago, when Nawapara, Rampur

and Lata Dadar were resettled.

Krishanu Chandraker, the range officer of Bar at the sanctuary established in 1976, said most of the families agreed to shift for better prospects. Only 10 families have stayed back in Rampur village, which lies in Bar panchayat. The rest 126 families moved to a place now called Srirampur in Mahasamund district.

According to Chandraker, the sanctuary had tigers until 2008. He hoped the relocation of the remaining villages would help reintroduce the big cat to the place. If that happened, the sanctuary area may go up to 500 sq km from the present 240 sq km.

Views of the Barnawapara Wildlife Sanctuary (Photo: Deepanwita Gita Niyagi)

“Animals need a good habitat and feel disturbed due to settlements inside the forest. Human-elephant conflict is a serious issue here. Farmers who face crop loss try to scare away the animals and that is when the conflict exacerbates. All 18 villages are willing to shift, but they have to seek permission from the gram sabhas where they want to settle down in future. We have shown people potential land sites,” he added. Compensation will amount to Rs 15 lakh per adult.

Odisha-based

wildlife conservationist Aditya Panda pointed out that

communities living inside forests have the choice of continuing their old ways

of life with limited access to schools, hospitals and markets. Alternatively,

people can choose improved livelihood opportunities by claiming the benefits of

voluntary relocation.

In Akaltara

village, farmer Ramji Netam told 101Reporters that many families have

submitted forms in the hope of quick relocation. They prefer to settle down in

Loharkot in Mahasamund district. The gram sabha of Loharkot has approved it,

according to the documents verified by this reporter.

In fact, Akaltara villagers have cleared the first and most important hurdle before those wanting to relocate — finding places where they are welcome. According to Fakir Bisal, who still resides in Rampur, the forest department has asked people to search for lands themselves. The government would simply facilitate the transfer of people and their belongings.

Documents indicating the intention of Bar's residents to relocate (Photos: Deepanwita Gita Niyogi)

For

instance, though people like Diwan got assurance about relocation from the

forest department and the gram sabha gave its consent to those who wished to

move out, no village has shown readiness to accept the residents of Bar.

Ketwas

recalled how people refused to allow a new settlement in their revenue

lands when the forest department took some potential resettlers to Bade Loram

village in Mahasamund to look at the land.

The grass

is greener

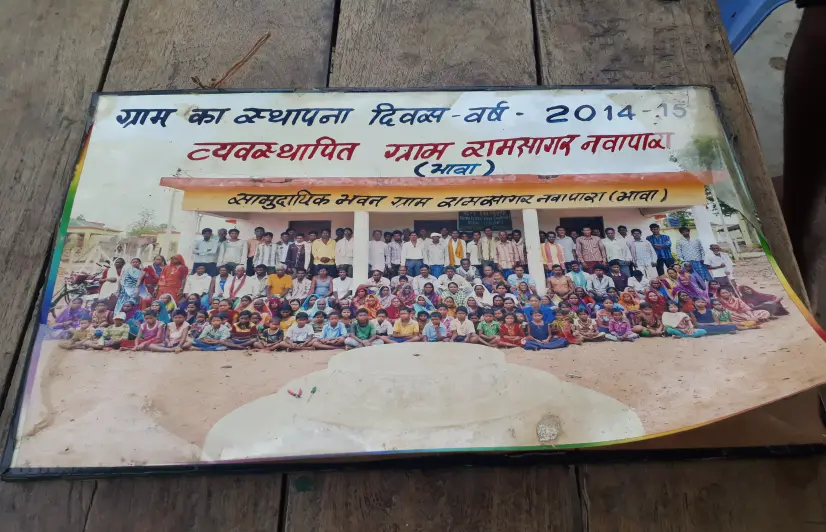

Nawapara

Ramsagar — it was called Nawapara before relocation — has both tribal and

non-tribal residents. With a population of 749, it comes under the Bhawa gram

panchayat and is located about 25 km from its original location. At the time of

shifting, Rs 10 lakh was

spent on each family for houses, farmlands

and amenities under the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning

Authority (CAMPA). It took two years to complete the government-sponsored housing,

equipped with three rooms, a kitchen and a bathroom.

“Usually, many people protest and refuse to relocate, but we left willingly as animals damaged our crops daily. Besides houses, we got five acres of land. It is much better here,” said Nawapara Ramsagar village chief Tejram Yadav. However, he admitted that the new place had drinking water scarcity.

Nawapara Ramsagar, the new home of the 750-odd former residents of Nawapara, where each family has identical government-sponsored housing with three rooms and five acres of land free of wild animals. But they have a scarcity of drinking water says mukhiya Tejram Yadav (left)

(Photos: Deepanwita Gita Niyagi)

For many, land is also the reason for shifting elsewhere. Jayant Kulkarni of Pune-based Wildlife Research and Conservation Society said people naturally felt apprehensive about shifting. The land they newly got would also take time to become suitable for cultivation.

Ketwas said

the settlers in Srirampur had complained that the lands they got were not

fertile and their new houses already had cracks in walls. “In fact, when it is the mahua collection season, they come back to their

old settlement in Rampur and live in makeshift shelters till the harvest. They

continue to have a deep connection with the forest,” she said.

To go or

not to go

Bisal is apprehensive that shifting elsewhere would undermine the adivasi culture. A resident of Rampur, he was offered five acres of land outside the sanctuary. But he did not leave because his son, though aged above 18, was deprived of the opportunity.

Sulochana Bai, a Kandha tribal from Rampur, recounted how people happily left the village then. “The lure of five acres of land offered to every adult aged above 18 made many people leave. Now, we are being put under pressure to shift.”

(Above) The last of Rampur's residents. Only 10 families remain here while the other 126 families have shifted to Srirampur in Mahasamund district; (Below) Rampur's sacred grove (Dev Gudi) that was allegedly destroyed by the forest department (Photos: Deepanwita Gita Niyogi)

“Rampur’s

condition is really sad. This time, the forest department did not allow tractors to enter the area for cultivation. They have no

ration cards, and their complete pension has been cut. People are sending their

kids elsewhere because schools and anganwadis have

been demolished. The forest department does not even employ them for any

work,” Ketwas said.

She added that Rampur has been taken off the map of Bar region, with the families that stayed put included in Haldi panchayat.

Those staying behind also alleged that the forest department damaged their dev gudi (sacred place of faith). Yet they are adamant that they will not leave. For people like Sulochana Bai, life is comfortable in the jungle, where the lands are fertile and the air is pure.

The cover picture, captured by Deepanwita Gita Niyogi, is a photograph of the original residents of Nawapara on relocation day.

Would you like to Support us

101 Stories Around The Web

Explore All NewsAbout the Reporter

Write For 101Reporters

Would you like to Support us

Follow Us On